Key Points

Key Solutions

|

Summary

When workers lose their jobs, unemployment benefits are a critical support as they seek new work. But the unemployment insurance (UI) system is still structured around the antiquated model of the white male breadwinner who works full-time. As a result, unemployed women are less likely to receive benefits than their male counterparts and bring home lower benefits when they do. Women of color and women facing other forms of structural discrimination confront even more significant barriers to receiving adequate support after a job loss.

Unemployment insurance (UI) is a lifeline for unemployed workers and their families and is one of the most effective means of bolstering the economy during a recession. Yet state laws and regulations exclude many working women and pay them lower benefits when they do qualify, undercutting workers, families, and economic growth.

States and the federal government must act to improve UI systems that fall far short for working women, strengthening a core pillar of the good-jobs economy.

Unemployment Insurance Is Vital for Women

At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the importance of unemployment insurance (UI) for U.S. women was unmistakable.[1] As millions of workers suddenly lost their jobs, Congress acted to temporarily expand UI eligibility, raise benefit levels, and extend the maximum duration of benefits nationwide. An analysis by the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that nearly 40 million U.S. adults—including almost 1 in every 6 women over age 18, a total of 20.8 million women—received UI benefits between March 13 and December 21, 2020.[2] The Census Bureau reported that UI benefits prevented 2.4 million women and 1.4 million children from falling below the poverty line in 2020 and millions more in 2021,[3] and some analysts made the case that the real impact on poverty was even greater.[4] In addition to women lifted above the poverty line, millions more reported better access to food, greater likelihood of staying current on rent or mortgage payments, and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety.[5] Economists described expanded UI as the most effective economic stimulus measure delivered during the COVID-19 pandemic.[6]

Unemployment benefits were especially critical for women during the pandemic because the economic downturn disproportionately impacted occupations with high concentrations of female workers, worsening existing racial, ethnic, and gender disparities. As a result of occupational segregation, Black and Latina women in particular were overrepresented in jobs in the leisure and hospitality industry and other underpaid service jobs most directly affected by pandemic shutdowns.[7] Latina women were especially likely to be pushed out of the workforce early in the pandemic.[8] At the same time, the pandemic closures of schools and daycares imposed caregiving demands that disproportionately fell on women,[9] with Black mothers experiencing the largest employment disruptions.[10]

Crucially, Congress temporarily expanded UI during the pandemic to include workers who had to leave their jobs to care for a child or other household member, so that many caregivers became eligible for UI benefits for the first time.[11] As a result of this and other UI enhancements, expanded unemployment benefits helped to alleviate the inequitable impact of the pandemic, reducing poverty most significantly for Black, Latinx, and Asian households.[12]

When a woman loses her job, the sudden loss of income and benefits may be a crisis for her and her family regardless of the overall state of the economy.

Despite the powerful benefits of expanded UI for women and workers of all genders, Congress allowed pandemic UI programs to expire in September 2021 without making permanent reforms to the UI system. The American Rescue Plan Act did provide a one-time infusion of funds for states to modernize and upgrade their UI systems, but this funding was later reduced by Congress and then clawed back further by the Trump administration.[13] Unemployed workers were left to depend on state UI systems that vary widely: Many states have eligibility rules that disproportionately exclude unemployed women, benefits that are too low and last too few weeks to sustain women and their families during a job search, and numerous barriers to access. Not only is the system unprepared for another economic downturn, but it is also falling far short in supporting women experiencing unemployment today.

Unemployment benefits remain a lifeline even when the economy is not in freefall. When a woman loses her job, the sudden loss of income and benefits may be a crisis for her and her family regardless of the overall state of the economy. For example, in August 2025, 955,223 women claimed UI benefits,[14]relying on this support to get by as they searched for new employment.

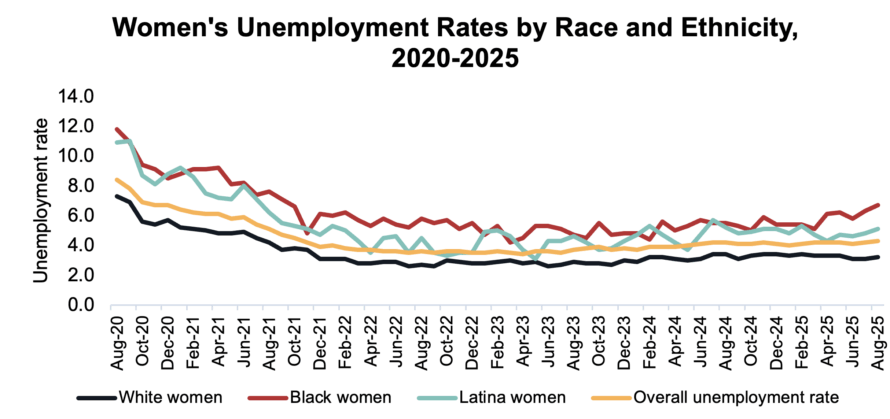

Despite a robust jobs recovery after the pandemic recession, women of color have continued to experience higher rates of unemployment than white men or women, reflecting the intersection of structural racism and sexism in the labor market, including discrimination in hiring.[15] Over the last five years, Black women consistently experienced above average unemployment rates, including a 6.7 percent unemployment rate in August 2025—more than double the 3.2 percent unemployment rate for white women.[16] Unemployment among Black women particularly surged as the Trump administration implemented mass layoffs of federal workers:[17] Black women are overrepresented in the federal workforce where they sought better benefits, job stability, and support from union and civil service rules that offered some protection against racism and sexism.[18] At the same time, the administration’s attacks on equal employment safeguards and diversity programs may be undercutting job opportunities for women of color more broadly.[19]

Figure 1: Unemployment Rates of Women by Race/Ethnicity Over the Last 5 Years |

|

| Source: Unemployment rate age 20 years and over, Latina women may be of any race, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics |

The unemployment rate for Latina women (who may be of any race) was 5.1 percent in August 2025.[20] Over the last five years, Latina workers have consistently experienced unemployment at a higher rate than white women. While unemployment rates for Indigenous workers are not reported on a monthly basis, the most recent data suggest that Indigenous women experience the highest unemployment of any demographic group,[21] reflecting structural racism and sexism as well as employment barriers specific to Indigenous communities.[22]

In addition to gender, race, and ethnicity, women’s experiences of employment and unemployment are shaped by multiple intersecting and overlapping influences which may include their disability status, sexual orientation, gender identity, status as parents or caregivers, citizenship, national origin, age, education, where they live, and other factors—all of which can subject them to systemic disadvantage, exclusion, and discrimination in the labor market. For example, in 2024 women with disabilities had an unemployment rate of 7.5 percent, the same rate as men with disabilities but significantly higher than workers who reported no disability.[23] At the same time, research suggests that LGBTQIA+ workers—and particularly transgender women—face higher unemployment rates than heterosexual and cisgender workers.[24]

During both recessions and periods of economic growth, unemployment benefits are critical for women of all backgrounds, particularly women facing multiple structural and social inequities. Yet too few women receive the support they need. The nation’s unemployment insurance system was built around an outdated model of the white, male, able-bodied, full-time worker with a caregiving wife at home. As a result, UI eligibility rules often exclude workers who don’t fit this model, such as part-time workers, low-paid workers, workers whose caregiving responsibilities prevent them from accepting certain jobs, and workers returning to the labor force after acting as full-time caregivers for children or other loved ones, among other groups of workers who are disproportionately likely to be women. The next section illustrates in greater detail how these access and eligibility barriers leave many unemployed women behind.

Access and Eligibility Barriers Block Unemployed Women from Receiving UI Benefits

In the first half of 2025, 30 percent of unemployed men received UI benefits compared to just 25 percent of unemployed women.[25] Researchers find that small but significant gender disparities in UI recipiency rates have persisted for decades.[26] These statistics reveal that UI is not reaching the majority of unemployed workers of any gender and that UI reform to expand eligibility and access would benefit workers broadly. At the same time, the findings also suggest that unemployed women face greater barriers than their male counterparts.

Unfortunately, data on unemployment claims are not reported intersectionally: The U.S. Department of Labor provides data on how many women workers claimed UI benefits and how many Black workers claimed UI benefits but not how many Black women workers claimed UI benefits. However, analyzing data on disparities in UI recipiency by factors such as race, age, and education suggests that Black and Latina women, younger women, women working without a union contract at their last job, and women with less formal education may be less likely than workers who are white, older, union members, or have more formal education to claim UI benefits when they are unemployed.[27]

This section explores specific barriers that hinder unemployed women from obtaining support from the UI system.

State rules on past earnings exclude many part-time and underpaid women from receiving UI benefits

To determine whether workers qualify for unemployment benefits, states use a variety of complex formulas to evaluate an unemployed worker’s past earnings and work hours.[28] These rules, known as “monetary eligibility” requirements, are intended to determine whether unemployed workers are sufficiently attached to the workforce: In practice, these requirements make low-paid, part-time workers ineligible for UI benefits in many states even if they have worked their entire adult lives.

Because of structural racism and sexism in the labor market, women—and particularly women of color—disproportionately work in low-paying positions with inconsistent schedules.[29] Women are also more likely than men to work part-time in order to manage childcare and other caregiving responsibilities.[30] LGBTQIA+ women also face discriminatory pay inequities, especially transgender women, and LGBTQIA+ women of color.[31] In addition, women and other workers with intellectual or developmental disabilities may legally be paid less than the U.S. minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, receiving very low pay.[32]

As a result, state UI eligibility rules that have stringent requirements for a high minimum income or hours worked exclude many women from receiving benefits.

Many states exclude women who need to leave their jobs from receiving UI benefits

Sometimes workers have no choice but to quit a job. Since women disproportionately take on caregiving responsibilities,[33] women in particular may be compelled to leave employment to care for a loved one during an illness or injury or to care for children when childcare becomes unavailable. And because women disproportionately experience intimate partner violence,[34] they are more likely to leave a job to escape domestic violence, assault, or stalking. Women and transgender workers are also more likely to face sexual and other harassment that pushes them out of a job.[35]

One study found that among states that expanded UI eligibility to include workers who quit for “compelling family reasons” such as those described above, mothers of young children were significantly more likely to receive UI benefits.[36]

In addition, women, like their male counterparts, may need to quit a job to have sufficient time to recover from a personal illness or injury, to deal with a loss of transportation to the worksite, to follow a spouse or partner who is relocating, or for other compelling reasons. While states have increasingly recognized that workers forced out of a job by factors such as these should be eligible for unemployment benefits, not all states have updated their laws accordingly. Even in cases where “good cause quits” like these are recognized, the process for verifying that a worker quit for good cause may be onerous and many workers may not be aware that they can claim UI benefits after quitting for a compelling reason and so many do not apply. One consequence is that women pushed out of a job may not receive unemployment benefits they need.

Women may be shut out of UI for seeking part-time work

In 2024, 732,000 unemployed women reported that they were looking for part-time rather than full-time work. These part-time job-seekers represented 23.6 percent of all unemployed women, compared to 14.6 percent of unemployed men who reported seeking part-time work.[37] In a previous survey, the primary reason women reported seeking part-time work was because of family or personal obligations, another reflection of women’s disproportionate caregiving responsibilities.[38] Workers with disabilities were also more likely to seek part-time work.[39] Yet according to the U.S. Department of Labor, 14 states mandated that workers must be able and available to work full time to be eligible for unemployment benefits, effectively disqualifying all workers seeking part-time employment.[40] Researchers find that states that expanded UI eligibility to workers seeking part-time employment significantly increased the likelihood that unemployed women would claim UI benefits.[41]

But most state UI laws have substantial limitations when it comes to part-time workers. Even among the states that allow workers seeking part-time jobs to qualify for UI benefits, most require that the worker have a prior history of working part-time.[42] In these states, a worker who had been employed full time but has new or increased caregiving responsibilities that now compel her to look for a part-time job could still not be eligible for benefits. These restrictions continue to disproportionately exclude female workers with caregiving responsibilities.

Requirements to be “able and available” and accept “suitable work” can disqualify women with caregiving responsibilities

To remain qualified for UI benefits, workers need to regularly certify that they are able and available to work and are actively seeking a “suitable” job. Workers who do not accept an offer of suitable employment can lose their UI benefits. Yet states vary widely in terms of what they consider “suitable,” often excluding women seeking jobs with work schedules that will allow them to meet caregiving responsibilities.

When researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis conducted focus groups with low-income women in Minneapolis and St. Paul who had recently experienced unemployment, they found that the need to be “able and available” created particular barriers for job-seeking mothers.[43] The authors highlighted the scarcity of affordable child care in the Twin Cities and nationwide and noted, “in participants’ experience, job requirements that are incompatible with family and school schedules, such as having to work evenings or weekends, made seeking employment as a parent difficult.”[44] A majority (74 percent) of study participants said child care responsibilities made finding a job harder, while researchers find the lack of child care combined with UI program mandates to be “able and available” was an obstacle to remaining qualified for UI benefits.

The UI system excludes women re-entering the labor force (or entering for the first time)

The UI system was designed to support workers with a recent work history, not people reentering the labor force or entering it for the first time. As a result, mothers looking for work after several years caring for children full-time at home are not eligible for UI benefits. Caregivers who spent years out of the workforce to care for a sick or disabled loved one are similarly shut out. Women who are recent graduates, self-employed workers, or are returning to the workforce after incarceration or a long illness are also excluded from UI eligibility while they search for work. Researchers suggest the reality that women are more likely to leave and re-enter the labor force than men is a major reason that unemployed women are less likely than men to be eligible for and receive UI benefits.[45]

Women face additional barriers to UI access

Even when women are eligible for UI benefits, they may face obstacles in accessing the support they are entitled to. Workers applying for UI benefits often face confusing state agency websites, incomprehensible forms, online portals that won’t display properly on a mobile phone, long wait times to access assistance, and a lack of translation and interpretation in the languages they speak.[46] UI applicants may face roadblocks in verifying their identity,[47] find their application for benefits improperly denied,[48] or have urgently-needed payments delayed for months.[49] Understaffed and under-resourced state UI agencies may be unable to adequately assist workers in navigating the complex UI system—a situation that would have been greatly improved by the $2 billion allocated to states to update their UI systems in the American Rescue Plan Act—if only Congress and the Trump administration had not first reduced and then clawed back this funding.[50] While these barriers may not have a gender-specific impact, they impede unemployed women’s ability to access UI benefits as well as people of other genders.

Women Receive Lower UI Benefits than Men, But Need Them More

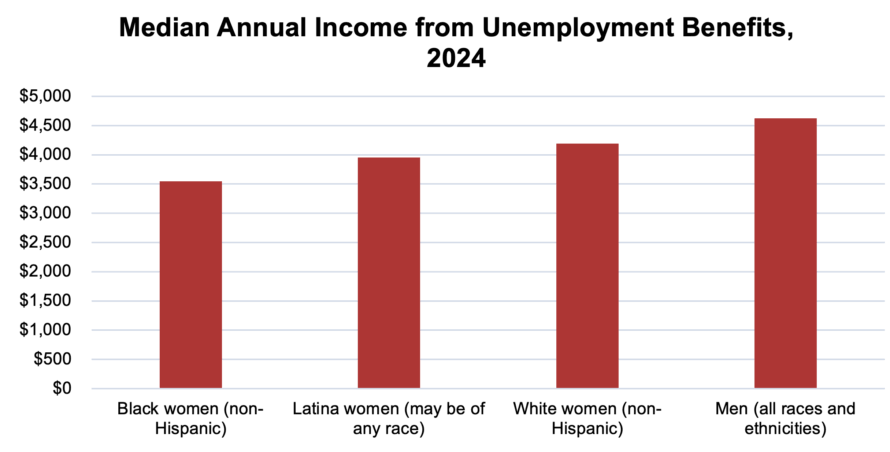

Even when women are eligible for UI and succeed in accessing support from the system, they typically receive lower benefits than men. Women’s median income from UI benefits in 2024 was $4,183 compared to $4,625 for men—a difference of $442 a year or 10.6 percent.[51] This is consistent with longer running trends: Researchers find that men’s median income from UI benefits was approximately 10 percent higher than women’s income from 2000-2017.[52]

Disparities in UI benefits are even greater for Black and Latina women. As Figure 2 indicates, Black women’s median income from UI benefits was $3,548 in 2024, while Latina women received $3,956, compared to $4,193 received by non-Hispanic white women.[53]

Figure 2: Median Income from UI Benefits by Race and Gender in 2024 |

|

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2025 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. |

Women’s lower UI benefits are a result of gender pay gaps

States generally calculate the dollar amount of unemployment benefits that workers receive each week based on their prior earnings. The goal is for UI to replace a proportion of workers’ past wages, but because women, and especially Black and Latina women are overrepresented in low-paying jobs due to structural racism and sexism,[54] state formulas for setting UI benefit amounts ultimately reinforce the same racial and gender inequality. Pay disparities shaped by other structural inequities would also be expected to show up in the form of lower unemployment benefits. Tipped workers, who are also disproportionately women of color,[55] are further disadvantaged when employers fail to report full tip amounts and as a result these earnings are not included in calculating benefit amounts.[56] The result is that many underpaid women, who lived paycheck-to-paycheck while employed, are unable to cover expenses on benefits that are only a small fraction of their prior paychecks.

Gender wealth disparities mean women have fewer resources to cope with unemployment

When workers lose their jobs and income, they usually cannot rely on UI benefits alone to pay bills and make ends meet while they search for work. For example, average weekly UI benefits were not enough to afford rent on a modest apartment in any state in the U.S. in 2024.[57] Because UI benefits are so low, unemployed workers often draw on other resources, such as personal savings and wealth, especially if they do not have additional household income from a still-employed spouse or partner. Yet here too women are at a disadvantage: The National Women’s Law Center found that in 2022, women who had never been married owned just $0.68 for every $1 owned by men who had never married.[58] Further, for every $1 of wealth owned by a never-married white man, never-married Black women owned $0.08 and never-married Latinas owned $0.14.[59] The analysis focused on single, never-married adults since wealth is often held at the household level, making it more difficult to evaluate gender differences within married couples. These glaring wealth disparities are a result of historic and ongoing discrimination compounded by systematic exclusion from wealth-building opportunities over generations for women of color.

Even as women typically have much less personal wealth than men to draw on, they are far more likely to be raising children on their own.

Research suggests women facing other forms of structural disadvantage are also likely to have the opportunity to build significantly less wealth that could be tapped during times of job loss.[60]

Even as women typically have much less personal wealth than men to draw on, they are far more likely than men to be raising children on their own.[61] Unemployed single mothers face the expense of supporting a family as well as greater challenges in balancing a job search and childcare. Women are also more likely to be unpaid caregivers supporting an ill or disabled family member.[62]

Longer UI Benefit Duration Helps Women Find Good Jobs

It takes time to find a job. Job searches may be especially lengthy for workers who face discrimination and structural barriers to employment due to their gender, race, ethnicity, disability, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, or where they live. Although men are typically unemployed for longer durations than women, race and ethnicity are complicating factors. For example, in 2024 the median white man was unemployed for 9.2 weeks (compared to 8.8 weeks median for white women), while the median Black woman was unemployed for 11.0 weeks and the median Latina woman was unemployed for 9.5 weeks.[63]

More prolonged job searches are not unusual: More than 1.1 million women were unemployed for 15 weeks or longer in 2024 and the average duration of unemployment for women was 21.1 weeks.[64] A longer period of unemployment puts women at greater risk of exhausting their unemployment benefits, meaning that even if they are approved for UI benefits and follow all state-mandated work search and other requirements to remain qualified, they could lose benefits simply for being unemployed for longer than the maximum duration of benefits. While many states provide up to 26 weeks of UI benefits (supplemented by additional extended benefits during periods of high unemployment) a number of states have sought to reduce costs by cutting the maximum duration of benefits: States including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee offered workers less than 15 weeks of UI benefits in 2025.[65] Not surprisingly, these are among the states where workers are most likely to exhaust UI benefits before finding work.[66]

Researchers conclude that providing additional weeks of UI benefits to women not only offers a much-needed financial lifeline but also significantly improves their prospects of finding a job that matches their educational background and qualifications, and that women, workers of color, and workers with fewer years of formal education benefitted the most from additional weeks of available benefits.[67]

Policy Recommendations

Women who are out of work should be able to sustain themselves and their families while they seek a new job. A strong unemployment insurance system prevents families from experiencing poverty and hardship as a result of job loss and fortifies the economy in times of economic turmoil, forming a core part of a good-jobs economy. Yet this brief has detailed how the UI system falls short for women, leaving them with inadequate benefit amounts, reduced duration of benefits, and a complex web of state eligibility rules that excludes many women altogether.

UI is a joint federal-state system, and its shortcomings can be addressed at both levels of government: States can improve their own UI systems, while the federal government can set standards that all states must meet, establish new federal programs that fill gaps in the system, and improve funding for UI administration and modernization.

States must act to strengthen UI for women

- Expand UI eligibility to include more women.

- Update monetary eligibility requirements to ensure low-paid and part-time workers, who are disproportionately women of color, are eligible to receive UI benefits. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on monetary eligibility.

- Ensure women who are compelled to leave their jobs—including mothers who suddenly lose childcare and survivors fleeing intimate partner violence—are eligible for unemployment benefits. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on good cause quits.

- Allow workers seeking part-time work—who are disproportionately women—to qualify for UI benefits regardless of whether they previously worked a part-time schedule. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on work search requirements.

- Sustain UI benefits for workers who turn down jobs that don’t match their caregiving responsibilities, ensuring that more women are recognized as “able and available” for work. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on suitable work.

- Establish an excluded worker program to provide unemployment support to immigrant women residing in the U.S. without legal status. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on excluded worker programs.

- Reduce the barriers women face to accessing UI benefits.

- Continue UI modernization efforts designed to improve equitable access. Under the American Rescue Plan Act, the federal government provided consultations, technical assistance, grants, and other resources to states to modernize their unemployment insurance systems, including by promoting equitable access. Although federal funding for UI modernization efforts was rescinded, states should seek to continue efforts that promoted UI access. Many resources including customer experience tools, compilations of best practices, and even open-source sample code for a UI application claim form remain available online. See the U.S. Department of Labor Office of UI Modernization customer experience resource page.

- Adopt plain language in all UI communications. Confusing, legalistic language on forms and letters can prevent women and men alike from accessing the benefits they are due. For additional details on using plain language to improve UI access, see NELP’s policy brief on plain language.

- Consider launching a community navigator program to help women and others from underserved communities understand and manage the process of applying for UI benefits. For more on state navigator programs, see this policy brief from the Center for American Progress.

- Ensure UI benefits are adequate to support women.

- Increase UI benefits to levels that sustain job-seeking women rather than reinforcing racial and gender disparities. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on UI benefit amounts.

- Implement a dependent allowance to provide additional funds to unemployed workers who are supporting children and others who depend on their income. States that already have a dependent allowance should assess whether the benefit amount is sufficient to meet financial needs. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on the dependent allowance.

- Maintain benefits long enough for women to find a good job.

Adjust benefit duration to support women who need more time to find their next job. Set the maximum duration of UI benefits to 30 weeks and ensure that all workers can qualify for the maximum duration. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on UI benefit duration.

- Adequately fund state UI benefits to strengthen UI for women.

Improve UI financing by broadening the state’s taxable wage base, indexing taxes to wages, reforming the employer tax system known as experience rating, and keeping businesses from dodging UI taxes by misclassifying workers as independent contractors. For detailed state policy recommendations, see NELP’s policy brief on UI financing and solvency.

The federal government must act to strengthen UI for women

- Enact the Unemployment Insurance Modernization and Recession Readiness Act.

Congress must pass the Unemployment Insurance Modernization and Recession Readiness Act, sponsored Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Representative Don Beyer (D-VA). The bill would set nationwide standards for UI, mandating that states offer at least 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, raising benefit amounts to replace a greater share of workers’ prior earnings, and increasing coverage for part-time workers, temp workers, and workers whose earnings fluctuate over time. These new federal requirements would reduce or eliminate many of the shortcomings of state UI programs that shut out women or consign them to inadequate benefit amounts and durations. The bill would also establish a new, federally funded Jobseekers Allowance to support jobless workers who would not otherwise be covered by unemployment insurance, including women returning to the workforce after periods of full-time caregiving, as well as new graduates, self-employed women, and women leaving incarceration. Finally, the legislation would modernize the Extended Benefits program that makes additional weeks of unemployment benefits available in times of high unemployment.

- Ensure adequate UI administrative funding.

State taxes pay for UI benefits, but the federal government funds state agencies to administer the UI program. According to the Government Accountability Office, between 2010 and 2019, annual funding available for state UI administration declined 21 percent, from approximately $3.2 billion to about $2.5 billion even as the U.S. workforce grew.[68] This chronic shortfall in administrative funding left state UI agencies understaffed, under-resourced, and often working with antiquated technology, leading to the failure to deliver UI benefits in a timely manner during the pandemic, when newly laid-off workers across the country confronted jammed phone lines, crashing websites, and long delays to access benefits, contributing to financial hardship for unemployed women and their families. Many of these shortcomings persist long after the pandemic.[69] Congress should adequately fund UI administration so that unemployed women can access the support they are due.

As discussed above, the federal government also provided a one-time infusion of funding to states under the American Rescue Plan Act, which was designed to help modernize UI systems, address major projects like technology upgrades, overhaul UI procedures, and improve access. The federal government should act to fully restore this funding so that states can complete modernization projects and improve their UI systems.

About NELP

Founded in 1969, the National Employment Law Project (NELP) is a nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated to building a just and inclusive economy where all workers have expansive rights and thrive in good jobs. Together with local, state, and national partners, NELP advances its mission through transformative legal and policy solutions, research, capacity-building, and communications. NELP is the leading national nonprofit working at the federal, state, and local levels to create a good-jobs economy. Learn more at www.nelp.org.

About The 75 Million Campaign

The 75 Million Campaign is a national movement that fights for the 75 million working women who power America’s economy to defend their rights, wages, safety, and opportunity at work. It opposes extremist attacks on workplace protections and holds policymakers and corporations accountable for advancing substantive economic justice for women.

Endnotes

[1] Most research and data sources continue to use a binary definition of gender, requiring respondents to identify as a man or a woman, and so limiting our understanding of the lives and experiences of people who identify with a different gender or no gender at all.

[2] Patrick Carey, et. al., “Applying for and Receiving Unemployment Insurance Benefits During the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Monthly Labor Review, (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 2021), https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2021.19.

[3] Emily A. Shrider, et. al., Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau, September 14, 2021), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html; John Creamer, et. al., Poverty in the United States: 2021 (U.S. Census Bureau, September 13, 2022), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-277.html.

[4] Will Raderman, Census Poverty Numbers May Underestimate Pandemic UI Impact by Half, (Niskanen Center, October 6, 2022), https://www.niskanencenter.org/census-poverty-numbers-may-underestimate-pandemic-ui-impact-by-half/.

[5] Carey, et. al., “Applying for and Receiving Unemployment Insurance.”

[6] Christopher Carroll, et. al., “Welfare and Spending Effects of Consumption Stimulus Policies,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2023), https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2023.002.

[7] The Impact of COVID-19 on Women (National Women’s Law Center, March 2021), https://nwlc.org/resource/the-pandemic-the-economy-the-value-of-womens-work/; Ariane Hegewisch, Women and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Five Charts and a Table Tracking the 2020 “She-Cession” by Race and Gender (Institute for Women’s Policy Research, January 28, 2021),.

[8] Kassandra Hernandez, et. al., Latinas Exiting the Workforce: How the Pandemic Revealed Historic Disadvantages and Heightened Economic Hardship (UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, June 14, 2021), https://latino.ucla.edu/research/latina-unemployment-2020-2/.

[9] Lindsay M Woodbridge, Byeolbee Um, and David K Duys, “Women’s Experiences Navigating Paid Work and Caregiving During the COVID‐19 Pandemic,” The Career Development Quarterly, Volume 69, Issue 4 (December 2021) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9015544/.

[10] Mark DeWolf, Liana Christin Landivar, “Mothers’ Employment Two Years Later,” U.S. Department of Labor Blog, May 6, 2022, https://blog.dol.gov/2022/05/06/mothers-employment-two-years-later; Jessica Washington, “‘One Paycheck Away From Losing Everything’: Why The Child Care Crisis Is Especially Hard for Black Mothers,” The Fuller Project, August 25, 2021, https://fullerproject.org/story/child-care-crisis-black-mothers-covid-pandemic-economy/.

[11] Unemployment Insurance Provisions in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (National Employment Law Project, March 27, 2020), https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/unemployment-insurance-provisions-coronavirus-aid-relief-economic-security-cares-act/.

[12] Frances Chen and Em Shrider, Expanded Unemployment Insurance Benefits During Pandemic Lowered Poverty Rates Across All Racial Groups (U.S. Census Bureau, September 14, 2021), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/09/did-unemployment-insurance-lower-official-poverty-rates-in-2020.html.

[13] Julie Su, Andrew Stettner, and Michele Evermore, Our Unemployment System Needs Modernizing. Trump Is Doing the Opposite, (The Century Foundation, September 10, 2025) https://tcf.org/content/report/our-unemployment-system-needs-modernizing-trump-is-doing-the-opposite/.

[14] “Characteristics of Unemployment Insurance Claimants: Total Claimants,” (Office of Unemployment Insurance, U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, August 2025), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/content/chariu2025/2025Aug.html. As discussed later in this brief, data on unemployment claims are not reported intersectionally (in other words, the Department of Labor reports how many women workers claimed UI benefits and how many Black workers claimed UI benefits but not how many Black women workers claimed UI benefits).

[15] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1MjJB.

[16] Data is for workers over age 20. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1MjJB.

[17] Valerie Wilson, “What’s Behind Rising Unemployment for Black Workers?” Working Economics Blog, (Economic Policy Institute, September 19, 2025) https://www.epi.org/blog/whats-behind-rising-unemployment-for-black-workers/.

[18] Erica L. Green, “In Trump’s Federal Work Force Cuts, Black Women Are Among the Hardest Hit,” The New York Times, August 31, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/31/us/politics/trump-federal-work-force-black-women.html.

[19] Lydia DiPillis, “Black Unemployment Is Surging Again. This Time Is Different,” The New York Times, October 12, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/12/business/economy/black-unemployment-federal-layoffs-diversity-initiatives.html.

[20] Data is for workers over age 20. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1MjJB.

[21] Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2023 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2024), Table 12a, https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2023/home.htm.

[22] Arohi Pathak, How the Government Can End Poverty for Native American Women (Center for American Progress, October 22, 2021), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/government-can-end-poverty-native-american-women/.

[23] Note that the unemployment rate measures jobless workers who are actively seeking employment and does not include people with disabilities who are not in the labor force. “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics – 2024,” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 25,2025, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/disabl_02252025.pdf.

[24] Sandy E. James et. al., Early Insights: A Report of the 2022 U.S. Transgender Survey (National Center for Transgender Equity, February 2024), https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/2022%20USTS%20Early%20Insights%20Report_FINAL.pdf; LGBT Demographic Data Interactive (The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, January 2019), https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=LGBT#demographic.

[25] Author’s calculations based on unemployment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and UI benefit claimant data from ETA 203 “Characteristics of Unemployment Insurance Claimants.”

[26] Eliza Forsythe and Hesong Yang, Understanding Disparities in Unemployment Insurance Recipiency (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022), https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/understanding-disparities-in-unemployment-insurance-recipiency/.

[27] Christopher J. O’Leary, William E. Spriggs, and Stephen A. Wandner, Equity in Unemployment Insurance Benefit Access (W.E. Upjohn Institute, 2021), https://research.upjohn.org/up_policypapers/26/; Elira Kuka and Bryan A. Stuart, Racial Inequality in Unemployment Insurance Receipt and Take-Up, (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2022), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/frbp/assets/working-papers/2022/wp22-09.pdf; “Characteristics of Unemployment Insurance Applicants and Benefit Recipients 2022,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 29, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/uisup.nr0.htm; Forsythe and Yang, Understanding Disparities in Unemployment Insurance Recipiency.

[28] Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws: 2023, (Office of Unemployment Insurance, U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, 2024), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/comparison/2020-2029/comparison2023.asp.

[29] Ofronama Biu, et. al., Job Quality and Race and Gender Equity: Understanding the Link between Job Quality and Occupational Crowding (Urban Institute, September 8, 2023), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/job-quality-and-race-and-gender-equity.

[30] “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Employed and Unemployed Full- and Part-time Workers by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity,” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024), https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat08.htm; “Does Part-time Work Offer Flexibility to Employed Mothers?” Monthly Labor Review, (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2022), https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2022/article/does-part-time-work-offer-flexibility-to-employed-mothers.htm.

[31] Sara Estep and Haley Norris, The 2024 LGBTQI+ Wage Gap (Center for American Progress, Jun 17, 2025) https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-2024-lgbtqi-wage-gap/.

[32] The subminimum wage for workers with disabilities was set to be eliminated in 2024, but the Trump administration withdrew this rule before it went into effect. “Employment of Workers With Disabilities Under Section 14(c) of the Fair Labor Standards Act; Withdrawal,” Federal Register, Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, July 7, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/07/07/2025-12534/employment-of-workers-with-disabilities-under-section-14c-of-the-fair-labor-standards-act-withdrawal.

[33] Katherine Gallagher Robbins and Jessica Mason, “Americans’ Unpaid Caregiving is Worth More than $1 Trillion Annually – and Women are Doing Two-Thirds of the Work,” National Partnership for Women and Families Blog (National Partnership for Women and Families, June 27, 2024), https://nationalpartnership.org/americans-unpaid-caregiving-worth-1-trillion-annually-women-two-thirds-work/.

[34] “Domestic Violence Statistics,” National Domestic Violence Hotline, https://www.thehotline.org/stakeholders/domestic-violence-statistics/.

[35] “Sexual Harassment in Our Nation’s Workplaces,” Data Highlight No. 2. (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, April 2022), https://www.eeoc.gov/data/sexual-harassment-our-nations-workplaces; Brad Sears, et. al., Workplace Experiences of Transgender Employees (UCLA School of Law Williams Institute, November 2024), https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/transgender-workplace-discrim/.

[36] Yu-Ling Chang and Leslie Hodges, “Did Unemployment Insurance Modernization Provisions Increase Benefit Receipt among Economically Disadvantaged Workers?” Social Science Review, Volume 98, Number 1, (March 2024) https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/728680.

[37] “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Employed and Unemployed Full- and Part-time Workers by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity,” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024), https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat08.htm.

[38] “Who Chooses Part-Time Work and Why?” Monthly Labor Review (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2018), https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/who-chooses-part-time-work-and-why.htm.

[39] “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics – 2024.”

[40] Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws.

[41] Chang and Hodges, “Did Unemployment Insurance Modernization Provisions Increase Benefit Receipt?”

[42] Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws.

[43] Mary Hogan and Amalea Jubara, “How Low-Income Women Experience the Unemployment Insurance System,” (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, April 3, 2025), https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2025/how-low-income-women-experience-the-unemployment-insurance-system.

[44] Hogan and Jubara, “How Low-Income Women Experience the Unemployment Insurance System.”

[45] Forsythe and Yang, Understanding Disparities in Unemployment Insurance Recipiency.

[46] For more on barriers to UI access, see Amy Traub, Federal Standards Needed to Provide Equitable Access to Unemployment Insurance, (National Employment Law Project, June 21, 2023), https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/federal-standards-needed-to-provide-equitable-access-to-unemployment-insurance/.

[47] Elizabeth Bynum Sorrell and Rachel Meade Smith, Digital Doorways to Public Benefits: Beneficiary Experiences with Digital Identity (Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation and Digital Benefits Network, September 11, 2025), https://digitalgovernmenthub.org/publications/digital-doorways-to-public-benefits-user-experiences-with-digital-identity/.

[48] Flannery O’Rourke, Workers Denied: How to Diagnose and Prevent Improper Unemployment Insurance Denials (National Employment Law Project, July 31, 2025), https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/workers-denied-how-to-diagnose-and-prevent-improper-unemployment-insurance-denials/.

[49] Michele Evermore, States Still Challenged in Making Timely Unemployment Payments to Laid Off Workers (The Century Foundation, March 27, 2024), https://tcf.org/content/commentary/states-still-challenged-in-making-timely-unemployment-payments-to-laid-off-workers/.

[50] Su, Stettner, and Evermore, Our Unemployment System Needs Modernizing.

[51] Author’s calculations based on U.S. Census Bureau Annual Social and Economic Supplement, Table PINC-08 https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-pinc/pinc-08.html.

[52] Unemployment Insurance and Protections are Vital for Women and Families (National Women’s Law Center, National Employment Law Project, Center for American Progress, and Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, December 2019), https://nwlc.org/resource/unemployment-insurance-and-protections-are-vital-for-women-and-families/.

[53] Author’s calculations based on U.S. Census Bureau Annual Social and Economic Supplement, Table PINC-08 https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-pinc/pinc-08.html.

[54] Jasmine Tucker and Julie Vogtman, When Hard Work Is Not Enough: Women in Low-Paid Jobs (National Women’s Law Center, April 2020), https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Women-in-Low-Paid-Jobs-report_pp04-FINAL-4.2.pdf.

[55] Nina Mast, Tipping is a Racist Relic and a Modern Tool of Economic Oppression in the South (Economic Policy Institute, June 18, 2024), https://www.epi.org/publication/rooted-racism-tipping/.

[56] Michael E. McKenney, “Billions in Tip-Related Tax Noncompliance Are Not Fully Addressed and Tip Agreements Are Generally Not Enforced,” Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, September 28, 2018, https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2018reports/201830081fr.pdf.

[57] Author’s calculations based on unemployment insurance data from the U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration and Out of Reach: The High Cost of Housing (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2025), https://nlihc.org/oor.

[58] Gender and Racial Wealth Gaps and Why They Matter (National Women’s Law Center, 2025), https://nwlc.org/resource/gender-and-racial-wealth-gaps-and-why-they-matter/.

[59] Gender and Racial Wealth Gaps and Why They Matter.

[60] See for example, Andrea E. Willson, Kim M. Shuey, and Vesna Pajovic, “Disability and the Widening Gap in Mid-Life Wealth Accumulation: A longitudinal examination,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, Volume 90, (April 2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2024.100896; LGBTQI+ Economic and Financial (LEAF) Survey: Understanding the Financial Lives of LGBTQI+ People in the United States, Center for LGBTQ Economic Advancement & Research (March 2023), https://lgbtq-economics.org/research/leaf-report-2023/.

[61] America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2023 (U.S. Census Bureau, November 2023),

https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/demo/families/cps-2023.html.

[62] Caregiving in the U.S. 2025 (AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, July 24, 2025), https://doi.org/10.26419/ppi.00373.001https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/ltss/family-caregiving/caregiving-in-the-us-2025/.

[63] “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Unemployed Persons by Age, Sex, Race, Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity, Marital Status, and Duration of Unemployment,” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024), https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat31.htm.

[64] Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.

[65] How Many Weeks of Unemployment Compensation Are Available? (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 6, 2025), https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/how-many-weeks-of-unemployment-compensation-are-available.

[66] Author’s calculations based on based on unemployment insurance data from the U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration.

[67] Ammar Farooq, Adriana D. Kugler and Umberto Muratori, Do Unemployment Insurance Benefits Improve Match and Employer Quality? Evidence from Recent U.S. Recessions (National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2022),

https://www.nber.org/papers/w27574.

[68] Thomas Costa, et. al., Unemployment Insurance: Pandemic Programs Posed Challenges, and DOL Could Better Address Customer Service and Emergency Planning (US Government Accountability Office, June 2022), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104251.

[69] Amy Traub, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and Sanjay Pinto, The Unemployed Worker Study (National Employment Law Project, 2025), https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/the-unemployed-worker-study/.

Related to

Related Resources

All resourcesNELP’s New York City Worker Justice Agenda

Policy & Data Brief

Why Lawmakers Must Remove the Labor Dispute Disqualification from Unemployment Insurance

Policy & Data Brief

Workers Denied: How to Diagnose and Prevent Improper Unemployment Insurance Denials

Policy & Data Brief