Summary

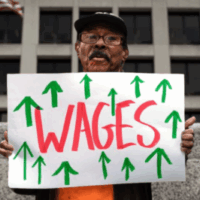

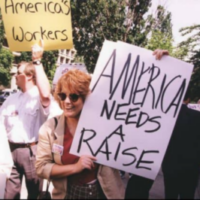

On April 18, 2018, Laura Huizar testified before the Colorado House Local Government Committee in support of HB 18-1368. The Bill would expressly grant local governments in Colorado the authority to adopt and enforce local minimum wage laws that could help localities better address the high cost of living in parts of the state and the pressing needs of workers in their jurisdictions.