In his first weeks in office President Biden announced policies addressing the way the government contracts for services. By reversing a ban on antidiscrimination trainings by contractors, calling for increased COVID protections for contracted workers on federal properties, and starting the process to raise contracted wages to $15 an hour, he demonstrated a commitment to his campaign pledge to improve the lives of working people and an acknowledgment of the market role our government plays when purchasing goods and services from private companies.

Federal contracting with private businesses is big business. In 2020, the federal government obligated $652 billion to contractual services and supplies with 5.5 million contracts. Successful low bids may rest on corporate practices of low compensation, high turnover, or even violations of labor law to keep costs at rock bottom. Provisions in the law that should protect workers can fail with insufficient accountability measures and underfunded enforcement regimes. As a result, important public work may be performed by workers who struggle to pay bills and rent, who have to work while ill, or who simply leave the job in frustration, taking their experience and knowledge with them.

Federal contracting with private businesses is big business. In 2020, the federal government obligated $652 billion to contractual services and supplies with 5.5 million contracts.

Yet workers’ voices and interests are rarely heard in discussions of federal contracting. This report shifts the narrative and puts workers and their stories at the center by focusing on those who do the day-to-day work on one critical contract. In 11 call centers located throughout the South and Midwest, employees of a company called Maximus work on a contract with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide timely and accurate support to those calling about their Medicare benefits or to access ACA healthcare through the Federally Facilitated Marketplace. We spoke with workers in different cities; with different gender identities; Black, brown, and white workers; and with varying family situations. A similar story echoed across their differences: Despite unsustainable wages and unaffordable health care benefits and fearing for their own safety without strong COVID protections, they need to perform essential and sensitive work during a national health crisis.

Despite unsustainable wages and unaffordable health care benefits and fearing for their own safety without strong COVID protections, [call center workers] need to perform essential and sensitive work during a national health crisis.

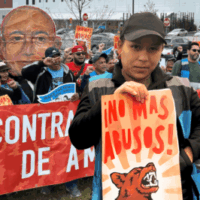

The majority of these workers are people of color and women. While low-cost contracting can depress the wages of all outsourced federal workers, Black contracted workers have long been the vocal “canaries in the coal mine” alerting us to this danger. Policy makers should listen to them and their coworkers now, and take action to support improved wages and conditions across contracted industries. Since Reconstruction, Black workers have provided critical leadership and solidarity with white workers and other workers of color to win labor standards. The Black call center workers fighting to improve conditions at Maximus are thus part of a long legacy that has—in fits and spurts—improved policies for Black workers and thus for all workers employed by private companies but ultimately paid with federal public revenues.

By listening to workers’ personal accounts together with an examination of data and details about this contract, we find that:

- Government agencies have failed to set fair wage rates under the Service Contract Act, which requires that federally contracted jobs do not undercut existing wages in a sector.

- Workers allege that Maximus has stolen the wages that workers were due and has failed to ensure these call centers are safe.

- A federal contracting policy that prioritizes the lowest cost over the best quality hurts the communities in which the workers live and jeopardizes the quality of services that callers receive.

- These harms fall disproportionately on women and people of color, who make up a large majority of the workforce on this contract, exacerbating long-term inequities in local labor markets.

- Workers’ efforts to organize across geographies and racial difference to improve conditions through collective action have been met with a campaign of fear and intimidation.

Finally, we suggest critical reforms to the federal contracting model that would improve not just these jobs, but millions of people in the private sector who perform the work necessary to keep the nation running. President Biden has started to make good on his promise to support working people. These call center workers, and millions of others working on contracts across every federal agency, are eager to see that process come to fruition and the value of the work they do for all of us recognized.

Download the report to read more.