This report shows how McDonald’s is failing in its legal duty to provide employees a safe work environment. In particular, the analysis demonstrates that McDonald’s long hours of operations—the longest among its national competitors—regularly put thousands of workers at risk due to the high levels of violence associated with late-night retail.

Introduction

In January 2019, a 16-year-old was working at the drive-thru of a McDonald’s in Camden, South Carolina when a customer drove up to her window, began an argument, and threw hot coffee in her face. The customer complained about waiting too long for an order of large fries.[1] That same month in Phoenix, Arizona, a customer threatened a McDonald’s employee with a shotgun when he did not receive hot sauce with his order.[2] In St. Petersburg, Florida, another McDonald’s customer was charged with battery after reaching over the counter and grabbing an employee because there were no straws at the condiment station.[3] Again in January—this time in Omaha, Nebraska—McDonald’s workers faced a gunman who demanded that they turn over the store’s cash. This marked the store’s second robbery at gunpoint in just six weeks.[4] And later in April, a 19-year-old worker in a Des Moines, Iowa McDonald’s was stabbed by two customers, angry over an $11 order, when the employee stepped outside for a break. [5]

For McDonald’s workers across the country, these anecdotes are not unusual or unique; they tell a bigger story. These narratives are indicative of a pattern of violence that occurs in their workplaces on a routine basis—from belligerent customers irate over missing ketchup or straws, to armed criminals demanding cash, and fist fights among customers in the lobby. In the last three years alone, the media has covered more than 700 incidents of workplace violence at McDonald’s stores across the United States. Yet, as shown below, the incidents covered by the media are only a small fraction of the total number of violent crimes that occur at McDonald’s stores each year. Verbal threats, harassment, and other types of assault often go unreported to the authorities. Regardless of media attention, these incidents of workplace violence regularly place both workers and customers at risk.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), workplace violence includes physical assault, threatening behavior, and verbal abuse that occur in a workplace setting.[6] This report outlines the extent and severity of workplace violence at McDonald’s stores. It includes an analysis of violent incidents reported in the media, violence data from St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, Illinois, and interviews with current and former McDonald’s workers who have experienced violence while on the job.

This report shows that McDonald’s is failing in its legal and moral duty to provide employees a safe work environment. In particular, the analysis shows that McDonald’s long hours of operation—which are the longest among its national competitors—regularly expose thousands of workers to risk due to the high levels of violence associated with late-night retail. [7] Interviews with workers suggest that McDonald’s is not sufficiently training staff or equipping its stores consistently with violence hazard controls, such as cash handling procedures, necessary visibility, panic buttons accessible to all staff, and safe drive-thru windows to prevent violence or at least minimize the number and severity of such incidents. Late-night hours, lack of training, and a lack of adequate hazard controls—combined with hundreds of reported violent incidents, and worker accounts of violence across the country—implicate McDonald’s in dangerous workplace neglect.

McDonald’s is the largest fast food company in the United States and the world.[8] In 2018, its nearly 14,000 U.S. stores generated $38.5 billion in sales, accounting for approximately 15 percent of all fast food sales in the country.[9] McDonald’s is the second-largest private sector employer in the United States and the world, with 1.9 million employees globally.[10]McDonald’s franchises 95 percent of its U.S. stores.[11] As the franchisor, McDonald’s exerts a high level of control over its franchisees’ operations, with detailed rules for all aspects of store design and operations, including required operating procedures, methods of inventory control, bookkeeping and accounting, days and hours of operation, business practices and policies, and advertising, among others.[12] McDonald’s is also one of the biggest real estate companies in the world. Under conventional franchising agreements, McDonald’s, in nearly all instances, owns or leases the land and buildings, which it leases or subleases to franchisees.[13]

McDonald’s puts fast food workers at risk

An analysis of the large volume of media-covered incidents reveals a disturbing pattern of violence that regularly takes place at McDonald’s stores. The media have covered at least 721 incidents of workplace violence that have taken place in a three-year period ending on April 15, 2019 at hundreds of McDonald’s stores across 48 states and Washington, D.C.[14] These incidents include shootings, robberies, sexual assaults, battery, and other forms of harassment and abuse. Many of the incidents stem from customers’ anger over petty grievances, such as a lack of straws, waiting too long, or missing items from their orders.

Even more alarming is that incidents covered by the media represent only a fraction of all incidents that take place at the fast food giant’s stores. McDonald’s workers are regularly subjected to verbal abuse, threats of physical violence, and other forms of harassment that are rarely reported to authorities, and consequently not covered by news media. Further, in large cities where gun violence has become shamefully routine, even those incidents that are reported to the authorities may fail to grab the attention of local media. In Chicago, for example, more than 21 calls are made on an average day to emergency services from McDonald’s stores in the city.[15] Most notably, one store had 1,356 calls made to 911 over a three-year period, but the media only covered two incidents at this store during this time.[16]

Even more alarming is that incidents covered by the media represent only a fraction of all incidents that take place at the fast food giant’s stores. McDonald’s workers are regularly subjected to verbal abuse, threats of physical violence, and other forms of harassment that are rarely reported to authorities, and consequently not covered by news media. Further, in large cities where gun violence has become shamefully routine, even those incidents that are reported to the authorities may fail to grab the attention of local media. In Chicago, for example, more than 21 calls are made on an average day to emergency services from McDonald’s stores in the city.[15] Most notably, one store had 1,356 calls made to 911 over a three-year period, but the media only covered two incidents at this store during this time.[16]

Similarly, crime data from St. Louis, Missouri also shows that the media only cover a fraction of all incidents that take place at the city’s McDonald’s stores. The St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department crime reports database lists 67 violent incidents occurring at city McDonald’s in the three-year period ending on April 15, 2018, compared to only three reports of violence at McDonald’s in the local news over the same period.[17] The three incidents covered by the media involved armed robberies, two of which occurred at the same store, which has been the site of five other robberies since April 2016.[18]

This is not the only store repeatedly hit by violent crime. For example, another St. Louis store just outside the city’s downtown area experienced 26 violent incidents in the last three years, including three robberies, three sexual offenses, and 20 assaults.[19] According to Elvira Gonzalez, a worker from a McDonald’s store in Chicago, she and her coworkers regularly experience violence on the job: “I have witnessed so many fights and robberies. Once, a man hit me on my back with a yellow wet-floor sign because he wanted to use the bathroom that I was cleaning. Another time, a customer got into a fight with the cashier and hit her. I almost got hit too but I ran and hid under a table. Another time, some men came into the store and stole my purse with all of my belongings.”[20] Ms. Gonzalez’s store has seen almost a dozen gun-related incidents in the last three years.[21]

“I have witnessed so many fights and robberies. Once, a man hit me on my back with a yellow wet-floor sign because he wanted to use the bathroom that I was cleaning.”

-Elvira Gonzalez, Chicago, IL

Gun violence appears to be pervasive at McDonald’s stores. Of the 721 media-covered incidents, guns were involved in 72 percent. Moreover, attackers used guns against store employees in 42 percent (306 incidents) of the covered incidents to threaten, pistol-whip, or shoot McDonald’s employees. In a notable case, a man shot the manager of a McDonald’s in Altamonte Springs, Florida in the neck after they got into an argument over a frappé order.[22]

Gail Rogers, a McDonald’s worker in Tampa, Florida, described her experience with gun violence at her job: “I was working in the lobby wiping tables when I noticed a customer using their personal cup to get soda out of the machine. I approached him and told him that he could not do that. At that point, the customer opened up his jacket, showed me a gun and put his hand on it. I backed away slowly, terrified for my life.”[23]

Violence at McDonald’s locations takes place in all areas of the store, from the lobby and bathrooms to the drive-thru and parking lot. Of the media-covered incidents analyzed, 62 percent occurred, at least in part, inside the store and 20 percent involved the drive-thru. Drive-thru incidents include cases where individuals attack workers or customers at the drive-thru window, gain access to the building by climbing through these windows, or commit armed robberies by brandishing a gun or some other weapon at drive-thru workers.[24] Forty percent of incidents occurred, at least in part, in the parking lot area, placing workers who exit the store—whether to bring food to drivers, discard trash, or just take a break—at risk.[25]

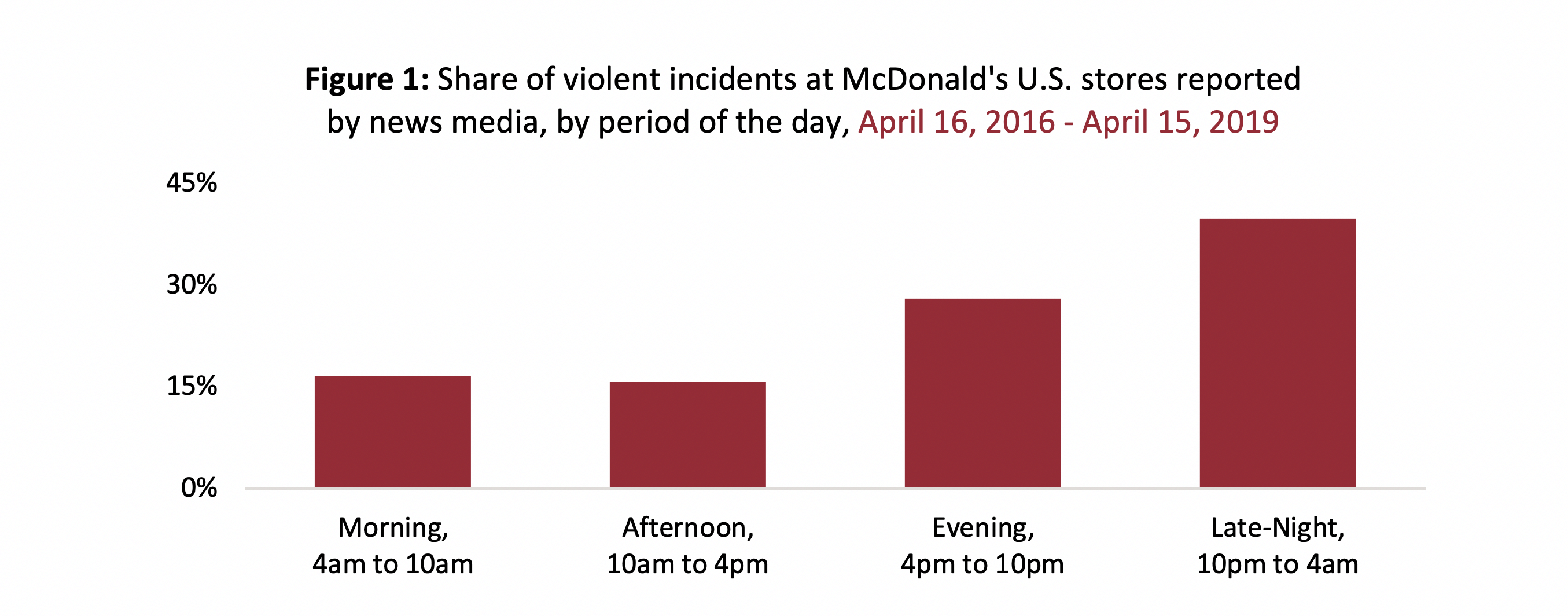

Violent incidents at McDonald’s occur at all times of the day, as Figure 1 shows. According to an analysis of the media-covered incidents of violence for which a specific time was reported, nearly a third of them occurred during the morning or afternoon.[26]

However, incidents that take place late at night—between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m.—account for a disproportionate share of the total incidents covered by the news media. Specifically, late-night incidents account for 40 percent of all media-covered incidents. Compared to other times of day, violent incidents were 40 percent more likely to occur during late-night hours than evening hours, and 145 percent more likely to occur than in the morning or afternoon.

Late-night crime may be associated with McDonald’s’ policies of extended hours of operation, which are the longest among its national competitors.[27] McDonald’s made it a priority to improve the stores’ convenience by extending hours of operation in its 2003 Plan to Win that the company credited with turning around the lackluster performance of previous years.[28] After the longer hours were introduced, McDonald’s executives continuously cited the move as a key driver of sales growth.[29] From 2003 to 2007, more than 90 percent of McDonald’s stores extended their hours, such that by 2007, nearly 40 percent of McDonald’s stores operated 24 hours per day, compared to less than 1 percent of stores in 2002.[30]

Today, McDonald’s stores are open, on average, just under 21 hours per day in the United States, as depicted in Figure 2.[31] McDonald’s average hours of operation are nearly three hours longer than Taco Bell and Burger King, which have the second and third-longest hours of operation of any national chain in the industry. Sonic, Chick-Fil-A, and Wendy’s operate their stores 14 to 17 hours per day, on average. Approximately 40 percent of McDonald’s stores are open 24 hours, compared to 6 percent of Burger King stores and 1 percent of Taco Bell and Wendy’s stores. Sonic and Chick-Fil-A do not operate 24-hour stores.

The risks of workplace violence are well known

According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), violence is a substantial contributor to death and injury on the job, especially in the retail and service industries. NIOSH and OSHA have identified a number of factors that put late-night retail workers at risk for workplace violence. The risk factors that apply to late-night retail are virtually the same as those that apply to late-night fast food operations, including direct contact with the public, exchange of money, working alone or in small numbers, working late at night or during early morning hours, and a lack of worker training in potential security hazards and how to protect themselves.[32]

Further, OSHA’s Young Workers Initiative, launched over a decade ago, and its E-tool on protecting young workers in restaurants, also clearly identify workplace violence as a key hazard facing workers in restaurants and provide solutions for employers to implement, with specific recommendations for protecting workers in drive-thru areas of restaurants.[33]

Late-Night Workplace Violence

NIOSH’s research informed the development of OSHA’s Guidelines for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments, which the agency first published in 1998 and last revised in 2009.[34] In this publication, OSHA recommends a number of commonsense protections that employers can implement to help protect workers from risk of injury or death from workplace violence, including improving visibility and surveillance, controlling customers’ access, developing emergency procedures to use in case of a robbery or security breach, using drop safes and limiting the amount of cash in registers, and increasing staffing levels at stores with a history of robbery or assaults. These guidelines also recommend implementing a strong follow-up program for workers who experience an incident to help them to deal with any psychological trauma; and training and education to ensure that all staff members are aware of potential security hazards and how to protect themselves and their coworkers through established policies and procedures.[35]

In addition to OSHA’s recommendations, various state and local governments have implemented legislation since the 1990s aimed at preventing assault for late-night retail workers.[36] For example, Washington and Florida adopted regulations for retail establishments with late-night operations, focusing on the training of employees and addressing aspects of the retail environment that may affect the risk of robbery.[37]

Many of these public initiatives, and the research underlying them, date back to the 1980s and 1990s, prior to the rise of late-night fast food in the mid-2000s. In 2007, however, a USA TODAY report detailed how the extended hours at McDonald’s and its competitors were driving an increase in violence against fast food workers.[38] The report found that in 2006, the number of homicides in the fast food industry was slightly higher than homicides of taxi drivers, and slightly less than homicides in convenience stores, at a time when both industries had a greater reputation for late-night violence risks. A security consultant and security manager for Wendy’s told USA TODAY that “increasing store hours increases the hours that the bad guys can rob you…Darkness to dawn is the highest time of exposure to armed robbery.”[39]

The human cost of workplace violence

Workers who endure episodes of violence, as either victims or witnesses, may experience both physical and psychological injuries, which can have a deleterious effect on their work and personal lives. Even though these workers are injured as a direct result of workplace hazards, they have few rights or protections in the wake of violent incidents. In the United States, the majority of fast food workers receive no paid sick leave or health insurance.[40] As a result, these workers are at the mercy of managers who may pressure them to continue working immediately after a traumatic incident.

Physical Injury

Violence in the workplace can have debilitating effects on the people involved. The most visible and obvious of these involve physical injury or death. Of the 721 incidents covered by the media over the three-year period discussed earlier, 39 percent resulted in the physical injury of at least one person, and 12 percent in death.

Workers who have been injured may be forced to take time away from work to seek medical attention, heal, and regain strength and wellness. According to NIOSH, shooting and stabbing victims typically take up to a month away from work, while other minor injuries usually force workers to take between three and five days off of work.[41]

Psychological Injury

Experiencing or witnessing workplace violence can also have a devastating impact on the victim’s wellbeing, sense of security, and quality of life. Victims may experience emotional shock and denial, which can worsen decision-making abilities and hinder active participation in daily life. Victims may also experience acute stress disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder, both of which can lead to difficulty sleeping, anxiety, and/or additional symptoms of distress.[42]

Graciela Rivera, a McDonald’s worker from Chicago who was assaulted while cleaning the store’s bathroom, explains: “The scariest thing that happened at work occurred while I was cleaning the bathroom and a man came in before I was done. When he came in, I tried to hurry out but I accidentally dropped the broom. When I bent down to pick up the broom, the man urinated on me, exposing his penis, and also said obscenities to me. I told my managers but they didn’t do anything. One manager just said that I’m always complaining about something.” While the man’s actions did not cause lasting physical harm, the incident caused significant emotional distress. “I felt humiliated. I felt like they didn’t take what happened to me seriously. I asked the manager if they were waiting for me to get seriously injured in order to actually do something to protect us,” said Ms. Rivera.[43]

“I was eating in the lobby of the restaurant near the front of the store when a group of people started fighting. One guy then went around the lobby threatening everyone while reaching into his pocket and signaling that he had a gun.”

– Darrell Miller, Kansas City, MO

Some workers report that McDonald’s managers do not allow employees to go home or take time off work to cope with their often-terrifying experiences. In 2018, Atlanta local media covered the story of a McDonald’s employee who was forced to continue working after she had a gun pointed in her face: “I can hardly sleep. If I do, it’s just flashbacks. I was traumatized because I never endured a situation like that before, period.” The worker told local WBS-TV Atlanta that her boss made her experience more difficult by pressuring her to stay on the clock: “I wanted to go home to my kids because I could have lost my life that day. My kids could have been motherless. [My managers] told me that they have been through storms, tornadoes, floods. I didn’t want to leave because I’m afraid of losing my job. If I walk out and lose my job, who is going to care for me and my kids?”[44]

Brenda Carbajal, a McDonald’s worker from Chicago, was disciplined by her manager for leaving the store after experiencing a second gun-related incident within a span of a few months. “I was coming back from my lunch break when all of a sudden the girls working at the front of the restaurant started running and yelling ‘He has a gun!’ and then I saw the man as he was walking around pointing the gun at my coworkers.” Ms. Carbajal and some of her coworkers hid in the freezer until the gunman left and resumed work once the police came to her store and investigated the incident. In the second incident, Ms. Carbajal witnessed a man pull a gun on a woman who was in the lobby as the woman was screaming for help. “They wanted us to keep working after the incident was over but I was so scared. The stress made me feel sick and all I wanted was to go home. I asked my manager if I could go home and she said no, but I decided to leave anyway. The following day when I came to work, they wrote me up for leaving.”[45]

“I was coming back from my lunch break when all of a sudden the girls working at the front of the restaurant started running and yelling ‘He has a gun”

– Brenda Carbajal, Chicago, IL

As Ms. Carbajal’s experience shows, violent incidents impact not just those who are directly victimized, but also those who bear witness to the violence. Darrell Miller, a McDonald’s worker from Kansas City, Missouri who witnessed a shooting at a McDonald’s, said: “I was eating in the lobby of the restaurant near the front of the store when a group of people started fighting. One guy then went around the lobby threatening everyone while reaching into his pocket and signaling that he had a gun. The fight then spilled outside and then people started shooting.” Mr. Miller added, “That was one of the worst and scariest experiences of my life. Everyone at the restaurant was scared for their life.”[46]

Maria Paez, a worker from San Francisco who also witnessed a shooting outside a McDonald’s store, recounted her experience: “I was leaving the store and suddenly someone started shooting outside of the store. I just ran and hid behind a car and covered my head. It was very surreal and for a moment I thought that I was dead. Ever since that incident, I feel traumatized. I don’t feel safe at work at all. I get really scared every time I hear customers arguing or yelling. You never know when someone might pull out their gun and start shooting.”[47]å

McDonald’s is not taking safety seriously

Under OSHA’s general duty clause, employers are required to provide a safe work environment for employees that is free of known hazards.[48] As a franchisor, McDonald’s exerts a high level of control over its franchisees’ operations, with detailed rules for all aspects of store design and operation, including required operating procedures, methods of inventory control, days and hours of operation, bookkeeping and accounting, business practices and policies, and advertising, among others.[49] Despite controlling most aspects of its franchisees’ operations, the alarmingly high number of violent incidents at McDonald’s stores across the country, and statements from McDonald’s workers, strongly suggest that the company has failed to effectively establish and enforce a standard violence prevention program across all of its stores. McDonald’s workers report a lack of standardized prevention tools such as accessible panic buttons and drop safes as well as lack of violence training and post-incident follow-up.

Interviewed workers report that they receive little to no training in violence prevention or instruction on how to deal with incidents when they arise. Martina Ortega, a worker from Chicago, explained: “I was in the kitchen when a woman who was in the lobby started screaming. The woman then jumped the counter and started grabbing the hot coffee pots and throwing them around. The woman then made her way to the back and started grabbing the bread and the biscuits and also threw them all around before she started removing her clothes. My coworkers and I ran outside. We had no idea what to do.” Ms. Ortega, who has worked at the same McDonald’s location for three years, also noted that she and her coworkers never received any violence training: “McDonald’s management should really be training us on how to deal with violent incidents, especially the cashiers who work face to face with the customers. We should be able to know where we need to run or what to do.”

Ms. Ortega’s case also suggests that supervisors and other store managers get little to no training in dealing with these types of incidents. She reported that after an incident took place, a store manager told employees that they could defend themselves by throwing hot coffee or hot oil at an attacker. Ms. Ortega, who understood that escalating situations might make them worse, pushed back against her manager’s advice: “That woman who attacked us obviously had some mental health issues. If we had thrown hot coffee or hot oil at her, we could have hurt her and maybe made her more aggressive.”

Interviewed workers report that they are often asked by management to confront patrons who are loitering, acting inappropriately, or are present at closing time, and escort them out of the store. Yet these workers have not received appropriate training on how to handle customers who may be belligerent, threatening, or who otherwise refuse to leave. In many cases, workers who have attempted to escort such customers out of the store have been attacked and, in some cases, killed. Christian McCoy, a former McDonald’s worker from a store in downtown Chicago, reported that on one occasion, his manager instructed him to escort out a homeless person who was soliciting money in the store’s lobby. When Mr. McCoy asked the man to leave, the man verbally threatened and then punched him.[50] This incident is reminiscent of a 2015 tragedy in which a 28-year-old McDonald’s employee was stabbed multiple times in the chest and neck by a vagrant whom the employee escorted from a Bronx, New York store. He died from injuries sustained in the attack.[51]

In addition to failing to provide training, many stores do not follow recommended hazard controls or administrative procedures around cash handling, visibility, and incident reporting. For example, McDonald’s does not appear to have a common set of cash handling procedures, including mandatory drop safes and limiting the amount of money held in cash registers, which reduces the amount of cash that employees can access, making these stores less valuable targets for thieves.[52] Cash control policies are one of the most effective robbery prevention methods. In the 1980s and 1990s, cash control and other hazard prevention policies helped convenience store chain 7-Eleven reduce robberies by 70 percent.[53]

Other safeguards, such as maintaining clear lines of sight such that employees have an unobstructed view of the street, and so police can observe what is occurring inside the store from the outside, are regularly ignored by McDonald’s, whose store windows are often plastered with marketing materials that obstruct visibility.[54] Moreover, McDonald’s stores with large drive-thru windows make it easy for criminals to gain access to the building, even if lobbies are closed. This is especially hazardous during late-night hours of operation when stores are run by skeleton crews. In a series of robberies in the St. Louis area in 2016, robbers took advantage of this vulnerability to enter and rob four different McDonald’s stores during late-night or early-morning hours of operation.[55]

There also appears to be minimal and inconsistent reporting of threats or acts of violence to authorities. Workers say that incidents are often not reported to authorities unless they result in serious physical injuries, significant property damage, or theft. Elvira Elena, a Chicago McDonald’s worker, said: “When we want to call the police, management just blows us off and says, ‘What do you want me to do? We will get in trouble if we call the police.’”

McDonald’s workers interviewed report a general disregard for worker safety at the stores they work at. By failing to institute proper violence prevention programs—from training and physical safeguards, to procedures for reporting—McDonald’s lack of a coordinated and effective plan places workers at risk and makes them feel powerless and vulnerable. Sonia Acuña, a worker from Chicago, explained: “I have raised my concerns and complained to my managers, but they won’t do anything. McDonald’s won’t do anything. We feel like we have to defend ourselves.”

Recommendations and conclusion

McDonald’s inadequate attention to the risk of violence and its consequences has invited danger into the workplaces and lives of McDonald’s workers across the country. McDonald’s needs to take the hazards of violence seriously and create a comprehensive program that covers all workers who wear the McDonald’s uniform. Specifically, the company needs to create a systemwide culture of violence prevention aimed at reducing the risk of violent incidents and minimizing the severity of physical and psychological injuries sustained by workers.

Below are recommendations that are informed by OSHA’s recommendations for workplace violence prevention programs, including the agency’s specific recommendations to protect workers in late-night retail and restaurants. Adoption of these practical measures can significantly address these serious threats to worker safety at McDonald’s.[56]

Recommendations

Hazard Prevention

Hazard prevention strategies can be classified into two categories: (1) engineering and environmental controls, and (2) administrative and work practice controls.

The following engineering and environmental controls should be implemented across the McDonald’s system:

- Improve visibility such that signs and other marketing materials located in windows do not block the line of sight for workers to the outside, or from authorities looking into the stores;

- Install a comprehensive surveillance and security system that includes video cameras, alarms, and panic buttons that all workers can access, along with drop safes—that employees cannot access—to limit the availability of cash and ensure that these security measures cover all work areas, including back entrances and trash receptacles;

- Install safer drive-thru windows that prevent unauthorized individuals from entering a store. In high-risk locations, such as stores with a history of robberies or assaults, and stores located in high-crime areas, install bullet-resistant drive-thru windows or pass-through windows;

- Prominently display security signage, such as cash-drop policies or CCTV monitoring, at all doors and front counters; and

- Implement store design elements that create barriers between employees and customers, thereby controlling customers’ access to the kitchen and other employee-only areas.

Administrative and work practice controls can include the following strategies:

- Ensure that all workers are properly trained on established policies and procedures;

- Adopt proper emergency procedures for employees to use in case of robbery or a security breach. These standard operating procedures should include guidance on when to call the police, when to trigger an alarm, and how to file charges after an incident;

- Increase staffing whenever possible, especially in stores with a history of robberies or in high-crime areas; and

- Require workers to report all assaults or threats of assault to a supervisor, and keep a log of such incidents.

Training

McDonald’s must ensure that all store workers are properly trained in violence prevention policies and procedures to minimize their risk of assault and injury. McDonald’s must provide sufficient resources to ensure that these trainings are conducted by qualified instructors who have a demonstrated knowledge of the subject. Training must include an overview of the risks of assault, recognizing and managing escalating hostile and aggressive behavior, operational procedures designed to reduce worker risk, the location and operation of safety devices and alarms, and policies and procedures for obtaining medical care, counseling, workers’ compensation, or legal assistance after a violent episode or injury. Moreover, McDonald’s should ensure that training is delivered in languages appropriate for the individuals being trained. At a minimum, OSHA recommends that employers provide training annually, or more frequently for establishments with high employee turnover.[57]

In addition to the general training for all staff, McDonald’s should provide supplemental training to supervisors, managers, and security personnel. Supervisors and managers should be able to recognize high-risk situations and make any necessary changes in the physical worksite and/or policies and procedures to eliminate those risks. Where present, security personnel need to be trained in handling aggressive and abusive store patrons, and strategies for de-escalating hostile situations.

Post-incident response

Post-incident response procedures are an essential part of an effective violence prevention program, and they must address the potential for both physical and psychological injury to workers. First, McDonald’s procedures should ensure that workers receive appropriate medical attention, guidance on reporting incidents to the police, and guidance on when to close the premises after an incident. Second, McDonald’s should provide access to free mental health services to workers who experience a psychological injury. Third, to avoid causing further distress to workers, McDonald’s should offer workers’ compensation and paid time off to victimized workers who are unable to return to work immediately after a violent incident due to physical or psychological injury. Lastly, McDonald’s should maintain records of all violent incidents, injuries, illnesses, hazards, corrective actions, and trainings. McDonald’s should use these records to evaluate the effectiveness of its violence prevention program, determine the severity of risks, and identify ongoing training needs.

Conclusion

Workplace violence is a preventable hazard. And McDonald’s workers—who for years have been raising their voices about low pay, sexual harassment, and other issues—are speaking up about the dangers posed by frequent violence on the job. Workers believe that McDonald’s is not doing enough to protect them from workplace violence and are now starting to call on the company to do better. In the aftermath of an attack on a female employee in St. Petersburg, Florida on New Year’s Eve 2018, workers from that city, along with those in Tampa and Orlando, led a walkout to demand better protection from workplace attacks. [58] “No one should have to fear for their own safety when they report to work each day, but it’s very clear I’m not safe at McDonald’s,” said Gail Rogers, one of the workers who participated in the strike.[59] “At McDonald’s, we’re subjected to all types of behavior that has no place at work. We won’t back down until McDonald’s takes responsibility for protecting all workers on the job.”[60]

[flipbook pdf=”https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Behind-the-Arches-McDonalds-Workplace-Violence.pdf”]

[1] Andrea Butler. “Report: Man threw hot coffee in McDonald’s worker’s face after waiting too long for fries.” WACH FOX 57. January 9, 2019. Available at: https://wach.com/news/local/report-man-threw-hot-coffee-in-mcdonalds-workers-face-after-waiting-too-long-for-fries

[2] Alexander Deabler. “McDonald’s customer threatened employee with shotgun for not getting hot sauce with fries.” Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/food-drink/mcdonalds-customer-threatened-employee-with-shotgun-for-not-getting-hot-sauce-with-fries

[3] “Florida McDonald’s employees to strike after viral video of St. Petersburg colleague attacked by customer.” Associated Press. January 7, 2019. Available at: https://www.abcactionnews.com/news/region-pinellas/florida-mcdonalds-employees-to-strike-after-viral-video-of-st-petersburg-colleague-being-attacked-by-customer

[4] “McDonald’s robbed at gunpoint.” WOWT NBC Omaha. January 22, 2019. https://www.wowt.com/content/news/McDonalds-robbed-at-gunpoint-504725831.html

[5] Ian Richardson, Tyler J Davis. “Police release images of 2 men accused of stabbing Des Moines McDonald’s employee over $11 drive-thru order.” Des Moines Register. April 3, 2019. Available at: https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/crime-and-courts/2019/04/03/des-moines-crime-mcdonalds-employee-stabbed-dispute-customer-over-order-police/3351697002/

[6] “Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments.” Presentation. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/dte/library/wp-violence/latenight/wpvnightretail.pdf

[7] We compared McDonald’s hours of operation against national competitors, those who have stores in most states, who serve breakfast lunch and dinner. Hours of operation means any time the store’s lobby or drive-thru are open. The chains analyzed included: Taco Bell, Burger King, Wendy’s, Sonic, and Chick-Fil-A. Data retrieved in April 2019.

[8] McDonald’s reported $38.5 billion in sales at U.S. stores in 2018, of which $2.665 billion was from company-owned stores and $35.860 billion was from franchised stores. See McDonald’s Corporation. Form 10-K. February 2, 2019. Pg. 22-23.

[9] The U.S. fast food market generated $256 billion in revenue in 2018. “Fast Food Restaurants in the US.” IBISWorld. October 2018. Available at: https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-trends/market-research-reports/accommodation-food-services/fast-food-restaurants.html

McDonald’s Corporation. Form 10-K. February 2, 2019. Pg. 22-23.

[10] Akin Oyedele and Skye Gould. “These are the 10 biggest employers in the world.” Business Insider. June 23, 2015. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/biggest-workforces-in-the-world-2015-6

[11] McDonald’s USA, LLC. Franchise Disclosure Document. May 1, 2019. Item 20.

[12] McDonald’s USA, LLC. Franchise Disclosure Document. May 1, 2019. Item 11.

[13] Chase Purdy. “McDonald’s isn’t just a fast-food chain—it’s a brilliant $30 billion real-estate company.” Quartz. April 25, 2017. Available at: https://qz.com/965779/mcdonalds-isnt-really-a-fast-food-chain-its-a-brilliant-30-billion-real-estate-company/

[14] Researchers used Google News to search for media accounts of violent incidents at McDonald’s restaurants using the following search terms: “McDonald’s robbery,” “McDonald’s shooting,” “McDonald’s fight,” “McDonald’s arrest,” “McDonald’s violence,” “McDonald’s sexual assault,” and “McDonald’s rape.” For each incident, we recorded the following details: date reported in the media, time and date of incident, McDonald’s address, nature and location of violence, weapons used, and reported injuries and/or deaths. Results from the Google News search were cross-checked the with the listing of gun violence incidents maintained by the Gun Violence Archive, a not-for-profit that provides public access to information about gun violence.

Available at: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/

[15] Analysis of Standard Location Reports released by Chicago’s Office of Emergency Management and Communications from April 16, 2016 to April 15, 2019. Standard Location Reports are based on the address of the occurrence. To exclude reports from addresses where multiple businesses operate from the same building, such as those located on the ground floor of skyscrapers or other mixed-used buildings, this analysis only includes data from stores that have a drive-thru.

[16] Id.

“Security Guard Assaulted Outside Downtown McDonald’s, Dramatic Cell Phone Video Shows.” NBC 5 Chicago. April 9, 2019. Available at: https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/Security-Guard-Assaulted-Outside-Downtown-McDonalds-Dramatic-Cell-Phone-Video-Shows–508323711.html

“Teen hit in face with hammer during fight over spot in line at McDonald’s.” ABC 13 Eyewitness News. June 27, 2018. Available at: https://abc13.com/teen-hit-with-hammer-in-fight-over-spot-in-fast-food-line/3663738/

[17] Researchers identified the three news stories searching Google and LexisNexis.

City of St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. Crime data from January 2016 to December 2018. Retrieved April 2019. Available at: https://www.slmpd.org/Crimereports.shtml

Paul Schankman. “Would-be robbers squeeze through drive-thru window at McDonald’s.” Fox 2 Now St. Louis. August 11, 2016. Available at: https://fox2now.com/2016/08/11/would-be-robbers-squeeze-through-drive-thru-window-at-mcdonalds/

Alexandra Martellaro, Kiya Edwards. “3 McDonald’s robbed through drive thrus.” KSDK-TV. June 27, 2016. Available at: https://www.ksdk.com/article/news/crime/3-mcdonalds-robbed-through-drive-thrus/63-257194799

Denise Hollinshed. “Police looking for gunman who robbed McDonald’s in St. Louis.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 19, 2018. Available at: https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/crime-and-courts/police-looking-for-gunman-who-robbed-mcdonald-s-in-st/article_c79f0fb9-580a-5603-ae22-069a100b5bcc.html

[18] Denise Hollinshed. “Police looking for gunman who robbed McDonald’s in St. Louis.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 19, 2018. Available at: https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/crime-and-courts/police-looking-for-gunman-who-robbed-mcdonald-s-in-st/article_c79f0fb9-580a-5603-ae22-069a100b5bcc.html

The robberies occurred at the 1919 S Jefferson Ave McDonald’s store. City of St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department crime data from April 16, 2016 to April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 2019. Available at: https://www.slmpd.org/Crimereports.shtml

[19] The incidents occurred at the 1119 N Tucker Ave McDonald’s store. Id.

[20] Interview with Elena Gonzalez in April 2019.

[21] Standard Location Report for the McDonald’s store at 1004 W Wilson Ave, Chicago, lists eleven different incidents involving shootings or reports of people with guns. Chicago Office of Emergency Management and Communications from April 16, 2016 to April 15, 2019.

Taylor Hartz. “Boy, 15, shot outside fast food restaurant in Uptown.” Chicago Sun-Times. October 14, 2018. Available at: https://chicago.suntimes.com/news/boy-15-shot-outside-fast-food-store-in-uptown/

“Man Gets Kicked Out Of Uptown McDonald’s, Shot.” CWB Chicago. April 14, 2017. Available at: http://www.cwbchicago.com/2017/04/man-gets-kicked-out-of-uptown-mcdonalds.html

[22] Joshua Rhett Miller. “Customer shoots McDonald’s manager over frappé order.” New York Post. June 2, 2017. Available at: https://nypost.com/2017/06/02/customer-shoots-mcdonalds-manager-over-frappe-order/

[23] Interview with Gail Rogers in April 2019.

[24] Josh Carter. “Armed robber enters Brandon McDonald’s through drive-through window.” WLBT. March 25, 2019. Available at: http://www.wlbt.com/2019/03/26/heavy-police-presence-responds-mcdonalds-brandon/

Amanda Burke. “Driver reports being shot at in Fall River McDonald’s drive-thru.” Providence Journal. April 4, 2019. Available at: https://www.providencejournal.com/news/20190404/driver-reports-being-shot-at-in-fall-river-mcdonalds-drive-thru

“Police arrest man for allegedly waving a loaded gun in McDonald’s parking lot.” Manchester Ink Link. March 18, 2019. Available at: https://manchesterinklink.com/police-arrest-man-for-allegedly-waving-a-loaded-gun-in-mcdonalds-parking-lot/

[25] Researchers reviewed each article covering the incident and identified the time and location of the incident. The figures add up to more than 100 percent because some incidents could take place in more than one locations (e.g. a fight that starts in the lobby and spills to the parking lot).

[26] Reports for 91 percent of the incidents indicated the time of the incident’s occurrence.

[27] Researchers compared McDonald’s hours of operation against national competitors, those who have stores in most states, who serve breakfast lunch and dinner. Hours of operation means any time the store’s lobby or drive-thru are open. The chains analyzed included: Taco Bell, Burger King, Wendy’s, Sonic, and Chick-Fil-A. Data retrieved in April 2019.

[28] McDonald’s 2005-Q4 Earnings Call. January 24, 2006.

[29] McDonald’s 2007 Annual Report. March 17, 2008. Pg.25. Available at: https://www.mcdonalds.com/dam/AboutMcDonalds/Investors/C-%5Cfakepath%5Cinvestors-2007-annual-report.pdf

McDonald’s 2008 Annual Report. March 12, 2009. Pg. 22. Available at: https://www.mcdonalds.com/dam/AboutMcDonalds/Investors/C-%5Cfakepath%5Cinvestors-2008-annual-report.pdf

McD Q2 2006 Earnings call transcript. July 25, 2006.

McD Q4 2007 Earnings call. January 28, 2008.

[30] Michael Arndt. “McDonald’s goes 24/7.” Bloomberg BusinessWeek. January 26, 2007. Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/16828944/ns/business-us_business/t/mcdonalds-goes/

[31] See Note 27. Hours of operation means any time the store’s lobby or drive-thru are open. To calculate the average hours of operation for each chain, researchers first calculated the weekly average opening and closing times for each store. Researchers then estimated the average hours of operation by subtracting the average opening time from the average closing time for each store. Lastly, researchers averaged the hours of operation for each chain.

[32] Id. Pg. 4 and “Violence in the Workplace.” The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). July 1996. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/96-100/risk.html

“Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2009. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3153.pdf

[33] “Young Workers – You Have Rights!” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/youngworkers/

Young Workers Safety in Restaurants E-Tool.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/youth/restaurant/index.html

[34] “Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2009. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3153.pdf

[35] Id.

[36] Robert C. Barish. “Legislation and Regulations Addressing Workplace Violence in the United States and British Columbia.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine, Volume 20, Number 2. 2001. Available at: https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(00)00291-9/pdf

[37] Id.

[38] Bruce Horovitz. “Late shift proves deadly to more fast-food workers; Deaths increase as restaurants stay open longer.” USA TODAY. December 13, 2007. Available on Lexis.

[39] Id.

[40] Only 37 percent of accommodation and food service workers have access to paid sick leave. Employee Benefits Survey. Bureau of Labor Statistics. March 2018. Available at:

https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2018/ownership/private/table32a.htm

Only 32 percent of accommodation and food service workers have access to paid sick leave, and only 20 percent of those workers actually participate in their employer’s healthcare program. Employee Benefits Survey. Bureau of Labor Statistics. March 2018. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2018/ownership/private/table09a.htm

[41] “Violence in the Workplace.” The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). July 1996. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/96-100/risk.html

[42] “ABCT Fact Sheets – Trauma.” Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Available at: http://www.abct.org/Information/?m=mInformation&fa=fs_TRAUMA

[43] Interview with Graciela Rivera in April 2019.

[44] Carl Willis. “Worker feared she’d be fired if she left after McDonald’s Robbery.” February 19, 2018. Available at: https://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/atlanta/worker-boss-wouldnt-let-her-leave-after-mcdonalds-held-up-at-gunpoint/703206615

[45] Interview with Brenda Carbajal in May 2019.

[46] Interview with Darrell Miller in April 2019.

[47] Interview with Maria Paez in April 2019.

[48] “Workers’ Rights.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2017. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3021.pdf

[49] McDonald’s USA, LLC. Franchise Disclosure Document. May 1, 2019. Item 11.

[50] Interview with Christian McCoy in April 2019.

[51] “McDonalds’s employee stabbed to death in Bronx.” Fox 5 News. January 4, 2016. Available at: http://www.fox5ny.com/news/mcdonalds-employee-stabbed-to-death-in-bronx

[52] Many media reports of robberies, including those of the 2016 robberies in St. Louis discussed above, indicate that robbers forced workers to retrieve money from the store’s safe, which indicates that those stores were likely not using drop-safes.

Paul Schankman. “Would-be robbers squeeze through drive-thru window at McDonald’s.” Fox 2 Now St. Louis. August 11, 2016. Available at: https://fox2now.com/2016/08/11/would-be-robbers-squeeze-through-drive-thru-window-at-mcdonalds/

Alexandra Martellaro, Kiya Edwards. “3 McDonald’s robbed through drive thrus.” KSDK-TV. June 27, 2016. Available at: https://www.ksdk.com/article/news/crime/3-mcdonalds-robbed-through-drive-thrus/63-257194799

David Hurst. “Westwood McDonald’s robbed at gunpoint, Police say.” The Tribune-Democrat. July 30, 2018.

[53] Scot Lin, Rosemary Erickson. “Stores Learn to Inconvenience Robbers: 7-Eleven Shares Many of its Robbery Deterrence Strategies.” Security Management. November 1998. Available at: https://www.questia.com/magazine/1G1-53286782/stores-learn-to-inconvenience-robbers-7-eleven-shares

[54] Google Streetview shows numerous stores whose windows are plastered with marketing materials.

[55] Alexandra Martellaro, Kiya Edwards. “3 McDonald’s robbed through drive thrus.” KSDK-TV. June 27, 2016. Available at: https://www.ksdk.com/article/news/crime/3-mcdonalds-robbed-through-drive-thrus/63-257194799

[56] “Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2009. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3153.pdf

[57] Id. Pg. 11.

[58] Danielle Wayda. “Florida Fast Food Workers Plan Strike in Response to Violent McDonald’s Incident.” Vice. January 7, 2019. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/ev33j4/florida-fast-food-workers-plan-strike-in-response-to-violent-mcdonalds-incident

[59] Id.

[60] Id.

“monitoring”by Yuya Tamai is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Related to

Related Resources

All resourcesWhen ‘Bossware’ Manages Workers: A Policy Agenda to Stop Digital Surveillance and Automated-Decision-System Abuses

Report

Delivering Precarity: How Amazon Flex Harms Workers and What to Do About It

Policy & Data Brief

REI Workers Speak Out: Racial Discrimination, Inequity, and the Fight for a Fair Workplace

Report