Executive Summary

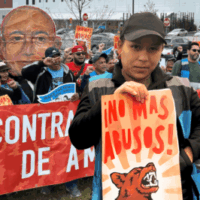

Workers across the economy—from fast food employees to journalists—are protesting employers who fire them without either advance notice, a good reason for doing so, a fair process, or even severance pay. A new nationwide survey of 1,849 adults in the U.S. workforce by the National Employment Law Project (NELP) and YouGov documents just how widespread unfair and abrupt firings are for U.S. workers and how harmful the impact is for workers and their families. Survey results also show that the threat of losing a job causes many to accept abusive or illegal working conditions. Finally, the survey finds strong support among workers across the political spectrum for greater job security protections.

Key findings from the survey include the following:

- More than two out of three workers who have been discharged received no reason or an unfair reason for the termination, and three out of four received no warning before discharge.

- Just one in three discharged workers receives severance pay. At the same time, more than 40 percent of currently employed workers—including more than half of Black workers—have only enough savings to cover one month or less of expenses if they were fired today.

- Half of all workers have been subject to electronic monitoring at work, and a majority have tolerated poor and often illegal working conditions due to concern about being fired for complaining.

- Two-thirds of workers support the adoption of “just cause” laws that would ensure workers receive a good reason and a fair process before losing their jobs. By a similar two-thirds margin, they support guaranteeing severance pay for all workers who are discharged.

The context for the new survey is the reality that almost everywhere in the United States, employees may be fired without a good reason, advance notice, or severance pay. This default rule, known as “at will” employment, can wreak havoc on the lives of workers and their families, when the paycheck they depend on is there one day and gone the next.

Workers in the new gig economy face similar hazards. The giant app corporations that employ rideshare drivers and delivery workers frequently “deactivate” employees—effectively ending their ability to work—without advance notice, explanation, or a fair process. This leaves workers with bills to pay, including lease and insurance payments for their work vehicles, but no source of ongoing income.

At-will employment also makes it easy for employers to retaliate against workers who speak up about concerns such as health and safety hazards, harassment, discrimination, and wage theft. In theory, laws prohibit employers from retaliating against workers who speak up and insist on their rights. But when workers can be fired for any reason or no reason at all, proving that a discharge was retaliatory is very difficult—and all but impossible for the majority of workers who cannot afford to hire a lawyer to help them. Because just cause protections “flip the script” by requiring employers to provide good reasons for discharges, they give workers more effective protection from being fired when speaking up about workplace concerns.

This new survey comes at a time when workers are organizing to replace at-will employment with a just cause standard. In 2019, parking lot workers in Philadelphia won the right to fight unfair firings with a just cause law.[1] In 2020, fast food employees in New York City won similar protections.[2] Workers in unions have continued to fight for just cause in their contracts. In recent years, journalists at publications ranging from the New Yorker to the New York Times’ Wirecutter to BuzzFeed have successfully fought for and won just cause protections in their union contracts.[3] And rideshare drivers won new legislation—first in Seattle and then in Washington statewide—protecting them against unfair terminations.[4]

Meanwhile, just cause is the employment law standard in much of the rest of the world and in most of the world’s other wealthy countries, including the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, Germany, and Japan. They all require employers to provide workers with a good reason and a fair process before terminating them.[5]

Amidst growing evidence of the harms caused by unfair firings—and growing public support for action to end them—federal, state, and local leaders should join with worker organizations to replicate and expand the new just cause laws to protect workers in all industries across the country.

Download the full report to read more.

Endnotes

[1] Juliana Feliciano Reyes, “City Council approves ‘just-cause,’ a cutting-edge worker protection law, for the parking industry,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 16, 2019, https://www.inquirer.com/news/just-cause-firing-bill-philadelphia-parking-lot-workers-seiu-32bj-20190516.html.

[2] Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, “No One Should Get Fired on a Whim’: Fast Food Workers Win More Job Security,” New York Times, December 17, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/17/nyregion/nyc-fast-food-workers-job-security.html; “Fired on a Whim: The Precarious Existence of NYC Fast-Food Workers,” Center for Popular Democracy, National Employment Law Project, Fast Food Justice, and SEIU 32BJ, February 2019, https://populardemocracy.org/fired-on-a-whim.

[3] Hannah Aizenman, Stefanie Frey, and Mai Schotz, “We Finally Won Just Cause Protection at The New Yorker after AOC and Warren Refused to Cross Our Picket Line,” Labor Notes, October 23, 2020, https://labornotes.org/2020/10/we-finally-won-just-cause-protection-new-yorker-after-aoc-and-warren-refused-cross-our.

[4] ”Seattle rideshare drivers gain legal protections from wrongful termination,“ King 5, July 1, 2021,

https://www.king5.com/article/news/local/seattle/seattle-rideshare-drivers-legal-protections-wrongful-termination/281-d289fe9b-2d87-42d1-b8f1-48412f660971; Tushar Khurana, “Hailed As Rideshare Driver Victory, New Law Lets Uber and Lyft Limit Labor Rights,” South Seattle Emerald, June 30, 2022, https://southseattleemerald.com/2022/06/30/state-rideshare-law-victory-for-drivers-or-national-campaign-to-deny-employee-rights/.

[5] See Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) s 387 (Austl.); KSchG § 1(2) (Ger.); Unfair Dismissals Act 1977 § 6(4) (Ir.); Labor Contract Act, art. 16 (Japan); Employment Rights Act, c. 18, § 98 (Gr. Brit.).