Thank you, Rep. Helen Head, Rep. Thomas Stevens and members of the House Committee on General, Housing and Military Affairs, for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Yannet Lathrop, and I am a researcher and policy analyst for the National Employment Law Project (NELP). NELP is a non-profit, non-partisan research and advocacy organization specializing in employment policy. We are based in New York with offices across the country. Our staff are recognized as policy experts on a wide range of workforce issues, such as unemployment insurance, wage and hour enforcement, and—as is relevant for today’s hearing—the minimum wage. We have worked with dozens of city councils, state legislatures and the U.S. Congress on measures to boost pay for low-wage workers and improve labor standards. We track both, the economic experience of state and local jurisdictions that have increased their wage floor, and the academic research on the minimum wage. As a result, we have developed a strong expertise on the analysis of minimum wage policy.

NELP testifies today in support of S.40, “An act relating to increasing the minimum wage,” which would raise Vermont’s minimum wage to $15 by 2024 and index it to inflation in subsequent years. This policy will help 87,000 struggling workers in Vermont better meet their basic needs. NELP also testifies against the adoption of a minimum wage exemption for young workers enrolled in secondary school, which a separate bill (H.712) under consideration by this Committee would do.

If Vermont approves a $15 minimum wage, the state would join a growing number of jurisdictions across the country that have enacted or are pushing for similar policies. Two of the nation’s biggest states—New York and California—with strong economies similar to Vermont, approved statewide $15 minimum wage policies last year, while Oregon adopted a slightly lower wage floor of $14.75 for most of the state. A growing number of other states—including Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maryland and Pennsylvania—are currently or will soon be considering similar $15 minimum wage legislation. In addition, more than two-dozen cities and counties from Washington, D.C. to Minneapolis to Flagstaff, Arizona have approved $15 minimum wage legislation of their own, or have campaigns underway.

The vast majority of the most rigorous modern research on the impact of higher minimum wages—including robust increases to $13 or more—shows that these policies boost worker earnings with little to no adverse impact on employment. The few analyses showing adverse effects—such as the University of Washington’s study of Seattle’s minimum wage increase—have been shown to have serious flaws that compromise the veracity of their findings, and tend to be driven by ideological concerns.

A robust minimum wage benefits now only low-wage workers, but also businesses and the economy as a whole. The benefits of higher minimum wages have been significant for affected low-wage workers and their families. They have raised pay for these workers in the face of larger economic trends that have led to stagnant and falling wages across the bottom of our economy. These measures also have been shown to reduce economic hardship, lifting workers out of poverty, and improving other life outcomes. The increased consumer spending triggered by higher wages can have the effect of boosting demand for goods and services and keeping money circulating in the economy, creating a virtuous cycle that benefits workers, businesses and the economy.

These positive benefits have led a growing number of business owners and economists to endorse a $15 minimum wage. In Washington, D.C., Senator Bernie Sanders introduced a $15 minimum wage bill, the Raise the Wage Act (S.1242), which was co-sponsored by 32 other U.S. Senators, including Senator Patrick Leahy. Its companion bill in the U.S. House of Representatives (H.R.15) was similarly strongly received, with more than 160 co-sponsors, including Congressman Peter Welch. The Raise the Wage Act, S.1242/H.R.15, would not only raise the federal minimum wage to $15, but would also gradually phase out the sub-minimum tipped and disability wages, and index it to the rise in the median wage.

In what follows, I will expand on these and other key points, and will summarize the economic evidence on the impact of the minimum wage.

The Need for a $15 Minimum Wage in Vermont

Workers throughout Vermont need to earn at least $15 per hour today, just to afford the basics; by 2024, they will need much more

Facing some of the highest costs of living in the nation, workers throughout Vermont need to earn more than $15 per hour today just to afford the basics. By 2024, they will need even more. As Appendix 1 shows, even single workers in the least expensive counties of Vermont (Essex and Orleans) need more than $19 per hour today. By 2024, these workers will need to earn an hourly wage of $22 or more. In these counties, single and married workers caring for at least one child—as well as all workers in Burlington, regardless of marital or parental status—need to earn significantly more.

Housing expenses, alone, can quickly drain the budgets of low-income families. The benchmark for affordable housing is 30 percent of income.[i] Yet, in Vermont, with housing costs continuously climbing while paychecks remain flat, an increasing number of low- and middle-income families are having to spend more than 30 percent of their total household budgets on housing.[ii]

Today, in rural Vermont, rent for a modest one-bedroom apartment averages $797 per month, or 44 percent of pre-tax earnings from full-time work at the current state minimum wage.[iii] In the Burlington metropolitan area, a one-bedroom apartment averages $1,080, or 59 percent of gross minimum wage full-time earnings.[iv] Rent for apartments with two or more bedrooms, which parents raising children would need, cost more and account for even larger percentages of gross monthly earnings. (See Appendix 2 for additional estimates by county or region, and apartment size).

The typical worker earning less than $15 in Vermont is a woman over 25 who works full-time and is likely to have at least some college experience

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) estimates that the overwhelming majority (86 percent) of Vermont’s workforce who would benefit from a $15 minimum wage are 20 or older, and 41 percent are 40 or older.[v] Additional key demographic characteristics of Vermont’s workforce impacted by this policy include:

- Gender: More than half (56 percent) are women.[vi]

- Race and ethnicity: While only 10 percent are workers of color, these workers tend to benefit more significantly. Looking at each racial or ethnic group separately, EPI finds that 63 percent of African Americans in Vermont, 28 percent of Latinos, and 40 percent of workers of Asian or other racial or ethnic backgrounds would benefit from a $15 minimum wage increase.[vii]

- Work hours: The majority (59 percent) work full-time.[viii]

- Education: A significant share (44 percent) of impacted workers have some level of post-secondary education: 28 percent have some college experience or have earned an Associate’s degree, and an additional 16 percent have a Bachelor’s degree or higher.[ix]

- Family income: Half of workers live in households with a family annual income of less than $50,000.[x]

The Case Against Minimum Wage Youth Exemptions

Vermont should reject harmful proposals that would exempt young workers from the full minimum wage

When minimum wage increases are proposed, some employers and lobbyists for low-wage industries argue that a lower minimum wage for young workers is necessary to encourage employers to hire teens despite their limited work experience, or to cushion the impact of a higher minimum wage on businesses. For example, H.712, which is also under consideration by this Committee, proposes expanding Vermont’s minimum wage exemption for workers enrolled in secondary school, from a school-year exemption to a year-round exemption.

Vermont should reject this and any other proposal than would enact a lower minimum wage for young workers, since it threatens real harm to teen and adult workers alike, while benefitting few employers.

As mentioned above, the vast majority (86 percent) of workers who would benefit from a higher wage floor are adults 20 or older, while teens make up only 14 percent of these workers.[xi] Given their small numbers, the benefits of a young worker exemption would be very modest for most Vermont businesses. Nonetheless, this policy would harm young and adult workers alike, as it could incentivize an increasing number of employers to hire young workers in place of adults and to adopt a high-turnover staffing model to maintain a young workforce. An indirect consequence of this policy would be to drive down wages for low-wage adult workers.

I expand on these points in the following sections.

Profitable fast food and retail chains with high-turnover staffing models would be the main beneficiaries of a young worker exemption in Vermont

A young worker exemption in Vermont would create a loophole in the law that would mainly benefit high-turnover businesses, and would encourage other employers to pursue that same harmful business model at the expense of good, stable jobs for workers.

Businesses that commonly adopt high-turnover staffing models are fast food and retail chains. Often, these employers pay some of the lowest wages, while posting high profits.[xii] According to some estimates, the rate of turnover for these businesses can be as high as 200 percent on an annual basis.[xiii] This is the equivalent of replacing their entire staff once every six months.

A young worker exemption would not only benefit large fast food and retail chains at the expense of teens, but it would also be unfair to small businesses and conscientious employers who already struggle to compete with big businesses while treating their employees of any age fairly.[xiv]

Expanding the state’s young worker exemption would harm all workers in Vermont, and would unwittingly advance corporate attacks against the minimum wage

In a recently leaked memo, corporate lobbyist and well-known minimum opponent, Rick Berman, outlined a multi-million dollar corporate strategy to undermine the nation’s growing support for a $15 minimum wage. That strategy includes pushing for young worker exemptions from the higher minimum wage.[xv]

Berman’s memo makes it clear that corporations view young worker exemptions not as policies that would create more employment opportunities or lead to better wages for young workers, but as a means to undermine public support for minimum wage increases and to drive down wages for all low-wage workers.[xvi]

Exempting young workers would harm college-bound teens from low- and middle-income families, who hope to use their earnings to pay some of their college expenses

In Vermont, as throughout the country, many young people struggle to meet the increasing costs of a post-secondary education. Although the proposed expansion of Vermont’s current young worker exemption would be limited to secondary school students, this policy could nonetheless have a negative effect for college-bound young workers from low- and middle-income families, who work long hours during their summer break to save for college.

High tuition and decreasing funds for grants and scholarships forces many college students to work long hours, which can compromise their graduation rates. Earning at least $15 per hour would enable many college-bound teens in Vermont to save money for tuition and other expenses, which would allow them to limit their work hours to 20 hours a week once they are in college. Choosing to do the opposite—exempting high school students from a $15 minimum wage—would hurt their career prospects and futures, as they would be forced to take out larger amounts of student loans, or work close to full time when in college, which would put them at risk of dropping out.[xvii]

According to the latest U.S. Census data, 9,000 young people in Vermont aged 19 and under worked in 2017.[xviii] Nationally, approximately half of all 18 and 19 year olds are students enrolled in two- or four-year college or university programs.[xix] The overwhelming majority of them (70 percent) work,[xx] as they struggle with rising tuition and cost of living, and the prospect a future mired by crushing student loan debt.

Low wages can put students at risk of poverty, adverse health outcomes and homelessness. Research also shows that many working college students struggle with poverty. A worrying two-thirds of the country’s community college students are food insecure, and 50 percent are housing insecure.[xxi] Food and housing insecurity can significantly affect college students’ health, wellbeing and ability to graduate.

A $15 Minimum Wage is a Pathway, Not a Cliff

The nation’s major public benefits programs generally incorporate gradual phase-outs, not “benefits cliffs;” as workers’ wages increase, their net incomes also increase

The nation’s broadest safety net programs—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP)—are designed to promote work and self-sufficiency. Therefore, rather than abruptly ending when workers’ incomes exceed a threshold, these benefits gradually phase out as workers’ incomes continue to rise.

In Vermont, raising the minimum wage to $15 is not going to lead to a ‘benefits cliff’ for most workers. EPI estimates that the majority of low-wage workers who would benefit are single or married adults without dependent children (80 percent), who work 40 or more hours per week (59 percent).[xxii] Childless adults are categorically ineligible for the Child Tax Credit; and workers with full-time (or close to full-time) hours generally earn too much to qualify for significant EITC, SNAP or Medicaid benefits. Thus, the vast majority of Vermont’s low-wage workers have very little by way of benefits to lose as their wages increase.

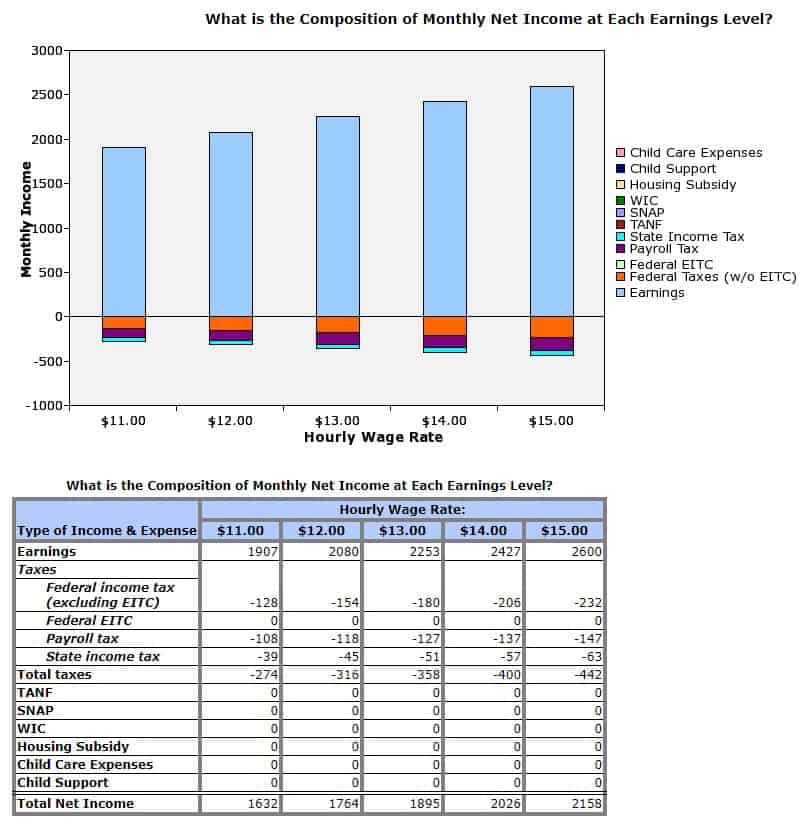

Figure 1, drawn from the Urban Institute’s Net Income Change Calculator (NICC),[xxiii] shows the net income change for a typical worker affected by the minimum wage—a childless adult working full-time—as the minimum wage rises to $15 per hour, factoring in federal and state taxes. The calculator shows that these workers earn too much to qualify for SNAP, even at a low wage of $11 per hour. It also shows that these workers retain the lion’s share of their higher wages—roughly 80 percent—as net income increases.

About 20 percent of workers affected by a $15 minimum wage are parents to dependent children.[xxiv] These parents are eligible for the Child Tax Credit, and some of them may also be eligible for other public assistance programs—mainly, the EITC and SNAP. These working parents may be vulnerable to the loss of benefits as their incomes increase. However, even these workers are net better off, as the benefits they may lose are more than offset by an increase in earnings.

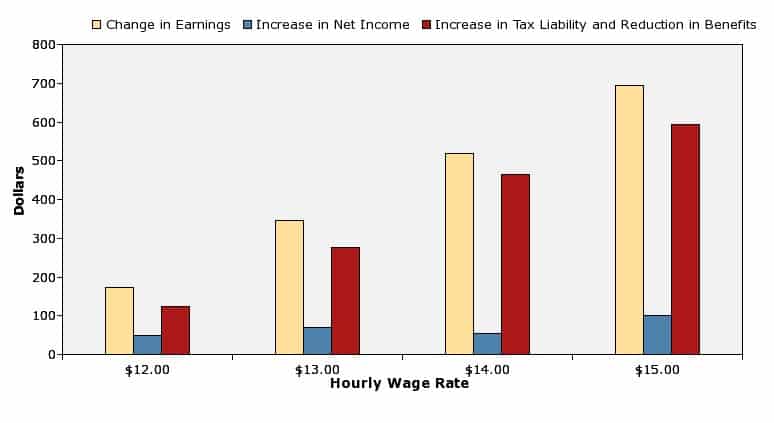

How much or how little they could lose depends significantly on the number of hours they work. A single adult working full-time, raising one child, and receiving EITC, SNAP and child care subsidies, will retain roughly 15 percent of her higher income as the minimum wage increases to $15 and her benefits—mainly SNAP and child care subsidies—phase down (Figure 2).

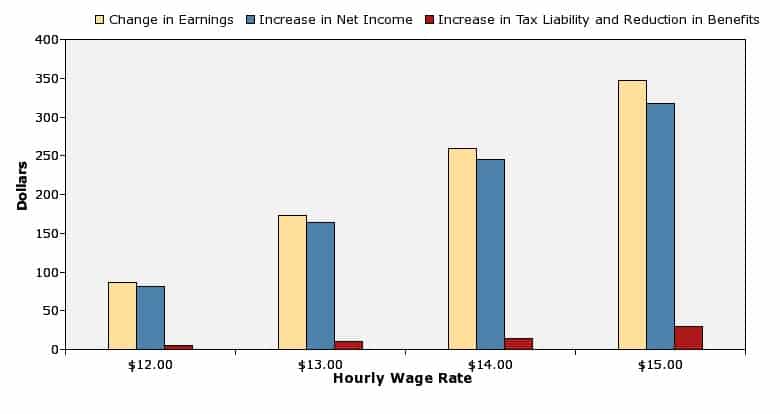

In contrast, a single worker raising one child, working 20 hours per week, and receiving all three benefits, will retain close to 100 percent of her higher income (Figure 3).

In reality, very few working households are at risk of facing cliff-like scenarios. Those who are, tend to be single parents raising two or more children in or near poverty (i.e., with earnings below 150 percent of the federal poverty line), and receiving EITC, SNAP and either cash or housing assistance (or both). According to analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, these cliff-affected families account for only 3 percent of all near-poor single-parent households with two children.[xxv]

Whenever cliff-like scenarios occur for working families, rather than placing blame on the higher minimum wage, those eligibility cliffs should be understood as the result of poor policy design. Vermont should use such occasions to review eligibility criteria for safety net programs, and make the required changes to ensure that working families with continued need of public support will retain their benefits.

The EITC is a complement to, not a substitute for, a $15 minimum wage

Opponents of a higher minimum wage sometimes argue that a better tool to increase the incomes of minimum wage workers is to expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which in Vermont functions as a refundable tax credit worth 32 percent of the federal EITC.[xxvi] Although no such proposals have been made in Vermont, it is worth considering this type of proposal briefly.

An expanded EITC—which is beneficial policy and worth pursuing—is a complement to, not a substitute for, a $15 minimum wage. A $15 minimum wage for Vermont would deliver an average income boost of $2,000 or more for 87,000 residents.[xxvii] Combined with an expanded state EITC, the higher minimum wage can have the greatest impact in helping working Vermonters make ends meet.

An expanded EITC by itself does not serve one of the additional functions of a higher minimum wage: Raising labor standards across the bottom of the economy, helping push up stagnant pay scales for workers earning moderately above the minimum wage, and ensuring that employers do their part in providing for their workforces. In particular, while the EITC is an important source of income for many low-wage workers (especially, those with dependent children), relying entirely on this tax credit to boost workers’ income essentially functions as a taxpayer subsidy to low-wage employers[xxviii]—which rewards and reinforces their choice to use a poverty-wage business model to realize profits.

Moreover, the EITC, as currently designed, leaves many low-income workers behind—in particular childless adults who work full-time. In Vermont, childless adults who earned more than $14,880 in 2016[xxix] (the equivalent of income from roughly 30 hours of work per week at the 2016 minimum wage rate of $9.60) did not qualify for the tax subsidy. And if these workers were younger than 25 or older than 65, they did not qualify at all, regardless of income.

That is why an expanded EITC and a $15 minimum wage work best together. A higher minimum wage raises pay broadly for workers at the bottom, and the EITC provides an additional income boost, chiefly for families raising children. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities explains, “Families modestly above the poverty line often can’t meet basic needs. Improving state EITCs and minimum wages together not only helps more families climb out of poverty, but also helps working families get further down the road to economic security.”[xxx]

That’s why the same states that are expanding their EITC programs are also raising their minimum wages, including Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington, D.C., Maryland and Minnesota.[xxxi]

The National Movement to Raise the Wage Floor, and the Benefits of a Higher Minimum Wage

A growing list of jurisdictions are enacting $15 minimum wage increases, reflecting continued concerns with low wages and popular support for bold change

With job growth skewed towards low-paying occupations over the past decade, there has been growing national momentum for action to raise the minimum wage. Although the U.S. median household income is slowly climbing from the depths of the Great Recession,[xxxii] hourly wages continue to stay flat or decline for most of the labor force.

The worsening prospects and opportunities for low-wage workers have prompted a record number of cities, counties, and states to enact higher minimum wage rates for their residents, often with overwhelming support from voters. Polling data shows that approximately two out of three individuals support a $15 minimum wage, and support among low-wage workers is even higher.[xxxiii] A poll of low-wage workers commissioned by NELP found that approximately 75 percent of low-wage workers support a $15 minimum wage and a union.[xxxiv]

Since November 2012, an estimated 19 million workers throughout the country have earned wage increases through a combination of states and cities raising their minimum wages; executive orders by city, state and federal leaders; and individual companies raising their pay scales.[xxxv] Of those workers, nearly 10 million will receive gradual raises to $15 per hour.[xxxvi]

More than two-dozen states and localities have adopted, and are currently phasing in, $15 minimum wage laws. Two of the nation’s biggest states—California and New York— approved statewide $15 minimum wage policies last year, while Oregon adopted a slightly lower wage floor of $14.75 for the majority of workers in the state. A growing number of states—including New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Maryland—are currently considering similar $15 minimum wage legislation.[xxxvii] In addition, more than two-dozen cities and counties from Washington, D.C. to Minneapolis to Flagstaff, Arizona have approved $15 minimum wage legislation of their own, or have campaigns underway.[xxxviii]

The trend in localities and states pushing for higher minimum wage rates is likely to continue as wages decline or stagnate, inequality worsens or remains high, and Congress fails to take bold action to ensure that hard-working individuals can make ends meet. (See Appendix 3).

Higher earnings resulting from minimum wage increases can have significant income, health and educational benefits for low-income individuals and their families

By raising pay broadly across the bottom of the economy, substantial minimum wage increases can have very direct and tangible impacts on the lives of affected workers and their families, and can be an effective strategy for addressing declining wages and opportunities for low-wage workers.

For example, analysis of San Francisco’s minimum wage policy—which, over the past decade, has remained significantly above the California and federal rates—shows that the City’s minimum wage boosted pay by more than $1.2 billion for more than 55,000 workers, and permanently raised citywide pay rates for the bottom 10 percent of its labor force.[xxxix] (San Francisco voters first approved an $8.50 minimum wage in 2003,[xl] at the time one of the highest in the nation. The widely recognized success of this measure led Mayor Ed Lee to broker an agreement with business and labor to place a new increase—this time to $15—on the November 2014 ballot, which voters overwhelmingly approved).[xli]

Research also shows that higher incomes resulting from a minimum wage increase can also translate to a range of other important improvements in the lives of struggling low-paid workers and their households:

- Decreased poverty: For workers with the lowest earnings, a study shows that the additional pay can increase their net incomes and lift them and their families out of [xlii]

- Decreased rates of child abuse and neglect: An analysis of child maltreatment rates found “evidence that increases in minimum wage reduce the risk of child welfare involvement, particularly for neglect reports and especially for young and school-aged children. Immediate access to increases in disposable income may affect family and child well-being by directly affecting a caregiver’s ability to provide a child with basic needs.”[xliii]

- Improved educational outcomes: A National Institutes of Health study determined that for children in low-income households, “[a]n additional $4000 per year for the poorest households increases educational attainment by one year at age 21.”[xliv]

- Improved graduation rates: A study by University of Massachusetts researchers found that high dropout rates among low-income children can be linked to parents’ low-wage jobs, and that youth in low-income families have a greater likelihood of experiencing health problems.[xlv]

- Improved health and wellbeing: A California study estimated that an increase in the state’s minimum wage to $13 per hour by 2017 “would significantly benefit [the] health and well-being” of Californians, and that they “would experience fewer chronic diseases and disabilities; less hunger, smoking and obesity; and lower rates of depression and bipolar illness. In the long run, raising the minimum wage would prevent the premature deaths of hundreds of lower-income Californians each year.”[xlvi]

Overview of the Economic Research on the Impact of Minimum Wage Increases

Decades of rigorous research shows that raising the minimum wage boosts workers’ incomes without adverse employment effects

The most rigorous minimum wage research over the past two decades, which examines scores of state and local increases across the U.S., demonstrates that these measures have raised workers’ incomes without reducing employment. The substantial weight of the scholarly evidence reflects a significant shift in the views of the economics profession, away from the simplistic view that higher minimum wages cost jobs. As Bloomberg News summarized in 2012:

[A] wave of new economic research is disproving those arguments about job losses and youth employment. Previous studies tended not to control for regional economic trends that were already affecting employment levels, such as a manufacturing-dependent state that was shedding jobs. The new research looks at micro-level employment patterns for a more accurate employment picture. The studies find minimum-wage increases even provide an economic boost, albeit a small one, as strapped workers immediately spend their raises.[xlvii]

One of the most sophisticated studies coming out of this new wave of minimum wage research, “Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders,” was published in 2010 by economists from the universities of California, Massachusetts, and North Carolina in the prestigious Review of Economics and Statistics.[xlviii] That study carefully analyzed minimum wage impacts across state borders by comparing employment patterns in more than 250 pairs of neighboring counties in the U.S. that had different minimum wage rates between 1990 and 2006.[xlix] Consistent with a long line of similar research, the study found no difference in job growth rates in the 250 pairs of neighboring counties—such as Washington State’s Spokane County compared with Idaho’s Kootenai County where the minimum wage was substantially lower—and found no evidence that higher minimum wages harmed states’ competitiveness by pushing businesses across the state line.[l]

The study’s innovative approach of comparing neighboring counties on either side of a state line is generally recognized as especially effective at isolating the true impact of minimum wage differences, since neighboring counties otherwise tend to have very similar economic conditions. The study was lauded as state-of-the-art by the nation’s top labor economists, such as Lawrence Katz of Harvard University, and David Autor and Michael Greenstone from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[li] (By contrast, studies often cited by minimum wage opponents, which compare one state to another—and especially those comparing states in different regions of the U.S.—cannot as effectively isolate the impact of the minimum wage, because different states face different economic conditions, of which varying minimum wage rates is but one.)

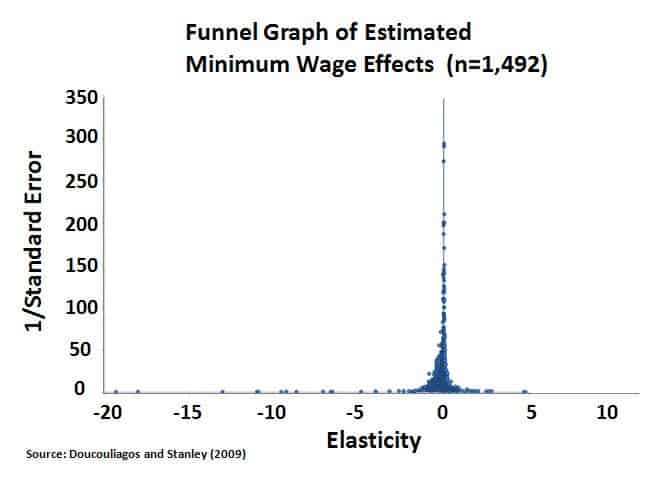

However, it is not simply individual studies, but the whole body of the most rigorous modern research on the minimum wage that now indicates that higher minimum wages have had little impact on employment levels. This is most clearly demonstrated by several recent “meta-studies” surveying research in the field. For example, a meta-study of 64 individual studies on the impact of minimum wage increases, published in the British Journal of Industrial Relations in 2009 by economists Hristos Doucouliagos and T. D. Stanley, shows that the bulk of the studies find close to no impact on employment.[lii]

This is vividly illustrated in Figure 4, below, which arrays the 1,492 different findings from 64 different studies, mapping their conclusions on employment impacts against the statistical precision of the findings. As economist Jared Bernstein summarizes, “the strong clumping around zero [impact on jobs] provides a useful summary of decades of research on this question [of whether minimum wage increases cost jobs].”[liii]

Drawing on the methodological insights of Doucouliagos and Stanley, a more recent meta-study by Dale Belman and Paul Wolfson reviews more than 70 studies and 439 distinct estimates to come to a very similar conclusion: “[I]t appears that if negative effects on employment are present, they are too small to be statistically detectable. Such effects would be too modest to have meaningful consequences in the dynamically changing labor markets of the United States.”[liv]

A recent study by University of California economists analyzed over three decades (1979 to 2014) of teen and restaurant employment data, comparing states with high average minimum wages and those with low average minimum wages (typically, equal to the federal minimum wage). The data did not show disemployment effects among restaurant workers—who comprise a large share of low-wage workers affected by a minimum wage policy—and the effect on teen employment was only a fraction of the already negligible impact claimed by minimum wage opponents.[lv]

Previously, in 2011, this same team of economists had analyzed the impact of the minimum wage on teen employment in a peer reviewed study, “Do Minimum Wages Really Reduce Teen Employment?”[lvi] The study carefully examined the impact of all U.S. minimum wage increases between 1990 and 2009—including those implemented during the recessions of 1990–1991, 2001 and 2007–2009—and found that the even during downturns in the business cycle, and in regions with high unemployment, the impact of minimum wage increases on teen employment was negligible.[lvii]

Similarly, in an analysis released near the end of the Obama Administration by the White House Council of Economic Advisors, economists examined all U.S. minimum wage increases since the Great Recession. Like the lion’s share of recent rigorous research on the minimum wage, they found that the post-recession increases delivered significant raises to low-wage workers with little negative effect on job growth.[lviii]

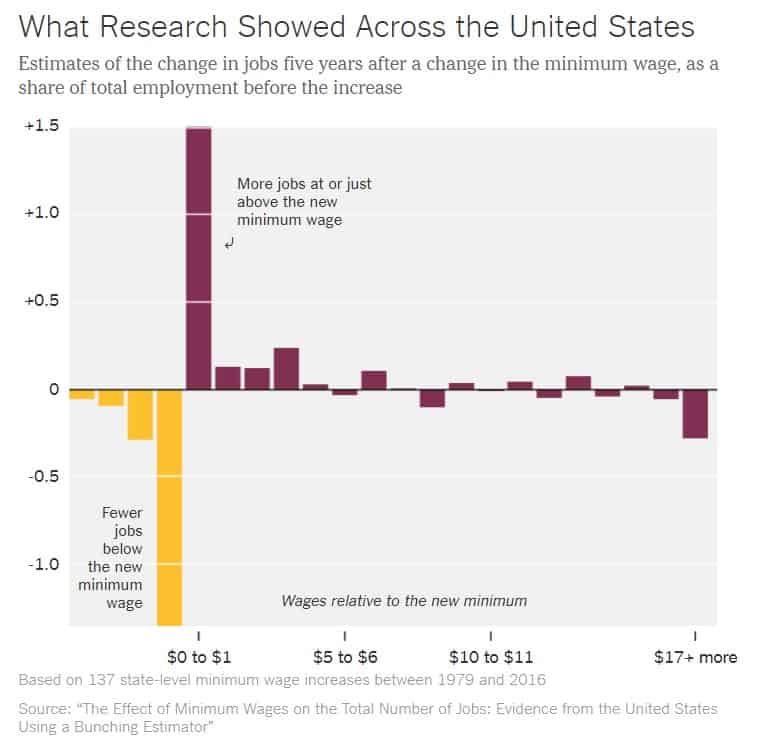

Finally, a more recent 2017 joint study by economists from the University of Massachusetts, the University College London and the Economic Policy Institute, examined nearly four decades of data (1979–2016), and came to similar conclusions. These researchers used a methodology that compares the number of jobs in various wage categories (rather than looking at total employment) prior to and following a minimum wage increase (“bunching method”), and found that jobs were not adversely impacted. The researchers concluded that any of the observed “job losses” were in fact the disappearance of jobs paying at or below the old minimum wage, with an equivalent increase in jobs at or slightly above the new higher minimum wage.[lix]

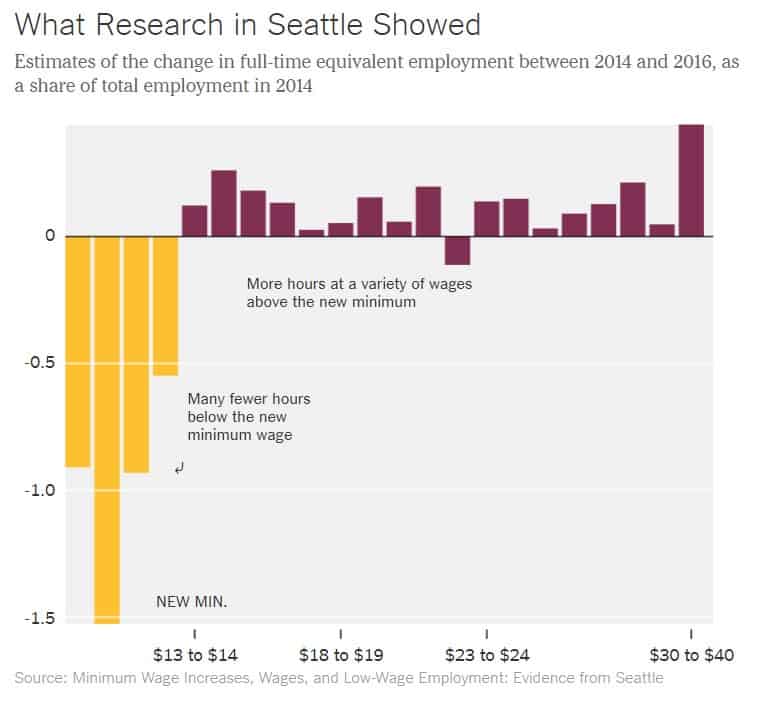

The University of Washington study of Seattle’s minimum wage ordinance has serious issues leading to dubious conclusions; it cannot serve as guide for policymaking

Last year, two separate teams of researchers—from the University of California at Berkeley, and the University of Washington—released conflicting analyses of the employment effects of the first two steps of Seattle’s $15 minimum wage ordinance. (The initial step increased the minimum wage from $9.47 to $11 for large employers in 2015, and from $11 to $13 in 2016). The study by the University of California, which focused on the restaurant industry during the 2015-2016 period, and which employed sophisticated controls, did not find negative employment effects.[lx] The University of Washington study, which has been criticized by leading economists for its serious methodological flaws,[lxi] found a reduction in low-wage jobs and hours worked.[lxii]

Chief among the study’s problems—which even the authors themselves admit that they “worry” about—are:

- Outsized Low-Wage Job Losses. The study’s main conclusion of substantial job losses is, ironically, also one of the first indicators that something is amiss with the analysis. The authors’ job loss estimates are far greater than those found for a synthetic control group, which they constructed made up of similar areas in Washington State where the minimum wage did not increase. Incredibly, the authors find a 9 percent decline in full-time-equivalent jobs paying under $19 an hour, compared with only a 3 percent increase in wages. This is the equivalent of a 3 percent job loss from a small 1 percent minimum wage increase. That is a job loss estimate that is far above what other researchers—including perennial minimum wage critic, David Neumark—have found in the handful of past studies showing a negative impact.[lxiii] Usually, if economists find a disemployment effect from an increase in the minimum wage, it is statistically insignificant or close to the zero mark.[lxiv] While one may be tempted to rationalize these outsized findings by pointing to the high nominal value of a $13 minimum wage, in reality this wage level is modest for a city like Seattle, which has been experiencing a boom in jobs and wages in recent years. One measure economists use to determine the strength of the minimum wage is the “Kaitz index,” or the ration of the minimum wage to the median hourly wage for full-time workers. A Kaitz index up to 55 percent is considered to be within the normal observed range, and in 2016, when the Seattle’s minimum wage rose to $13, ratio was approximately 51 percent.[lxv] Thus, with a minimum-to-median wage ratio in the range of normal, it is reasonable to expect that any observed employment effects will also be within the bounds of past minimum wage research. But as explained above, a 3 percent job loss from a 1 percent wage increase is an outsized disemployment estimate that is far greater—up to 10 times greater, according to one estimate[lxvi]—than past research. And that points to fundamental problems with the study’s methodology and data.

- Large Growth in High-Wage Jobs. While finding that low-wage jobs paying under $19 per hour saw a substantial decrease (9 percent) since the minimum wage ordinance went into effect, the authors also find a significant increase (21 percent) in higher-wage jobs that pay more than $19 per hour,[lxvii] including those in the $30 range[lxviii]—parts of the wage distribution which should not be influenced by a moderate minimum wage increase. This nonsensical conclusion points to a failure to control for Seattle’s booming economy, which has been experiencing rapid job growth and low unemployment rates over the past few years.[lxix] Tight labor markets, like Seattle’s, put pressure on employers to voluntarily raise wages in order to attract and retain staff, which results in a shift toward higher-paying jobs, independent of the minimum wage law. Hence, a more logical interpretation of the observed decrease in lower-wage jobs and increase in higher-wage jobs is not that Seattle’s $15 minimum wage ordinance was causing job losses, but rather, that market forces were naturally changing the city’s wage distribution towards higher wages without significant reductions in employment. Economists point to the study’s lack of a “spike” in the number of hours worked at the new minimum wage as evidence supporting this interpretation. They write,

- “Rather than a smooth distribution of workers at and above any statutory minimum wage, a regular feature of local, state, and federal minimum wages is that there are noticeably more workers who earn exactly any new minimum wage than there are just above the new minimum. This reflects the tendency of a new higher minimum wage to sweep workers who were below the new minimum just up to the new higher level, while leaving many (though not all) workers just above the minimum wage at or near where they were. In graphs of the wage distribution, this phenomenon creates a ‘spike’ in employment at exactly the new minimum wage. The fact that…the authors fail to detect any new spike due to the minimum wage increase to $13.00, again suggests that the study is not estimating the true effects of the minimum wage and instead merely [reflects] wage growth in Seattle that is occurring regardless of [the] minimum wage increase.”[lxx]

Figure 5, below, shows a graphical representation of the University of Washington’s findings for Seattle (which does not show a spike), and of findings for 137 minimum wage increases over nearly 40 years, which do show a clear spike in the 5 years after the minimum wage increases.

Thus, the paradox of low-wage job losses in tandem with higher-wage job increases, and the lack of a spike, both point to the University of Washington researchers’ erroneous interpretation of the data and the unreliability of their findings.

- Exclusion of 40 Percent of the Workforce from Its Analysis. Another feature of the study that casts serious doubts on its conclusion is the authors’ exclusion of nearly 40 percent of the state workforce. Because the data did not allow the researchers to identify whether individual workers employed by businesses with multiple locations throughout Washington, work within or outside of Seattle, they left those workers out of the analysis. As a result, the study paints an incomplete picture of the true effects of the minimum wage increase, and fails to determine if the ordinance might have been switching employment from single-location businesses to multiple-locations establishments. (In fact, economic theory suggests that minimum wage increases can result in the elimination of the lowest-paid jobs, such as those that may be more typical in single-location businesses, and their replacement with jobs in higher-wage businesses).[lxxii]

Experts find other areas of concern with the University of Washington study. However, these three flaws, by themselves, are significant enough that the study cannot be relied upon to paint an accurate picture of the employment effects of Seattle’s $15 minimum wage ordinance, or to guide Vermont’s debate over whether or not to adopt similar legislation.

Evidence from cities that were early adopters of high minimum wages similarly shows little adverse effects on jobs, and that implementation is manageable for employers

Beginning with SeaTac, Washington in 2012—joined later by Seattle, San Francisco, Minneapolis and dozens of other local jurisdictions—U.S. cities have been at the forefront of the movement to raise minimum wages to significant levels up to $15, forging a path for states to do the same. Academic studies and the media are beginning to report on the experience of these cities, documenting the effects these policies are having on local economies. To date, both research and business press reports suggest these measures are boosting pay with little negative impact on employment.

Seattle. This past June, the team of University of California economists released a study that explored the impact of Seattle’s higher minimum wage, which this year hit the $15 mark for large employers. The study focused on the restaurant industry—the largest low-paying sector where any negative effects on jobs would first appear. The study found that Seattle’s minimum wage, which ranged from $10.50 to $13 during the period analyzed, had raised pay for workers without any evidence of a negative impact on jobs.[lxxiii]

Another much-publicized Seattle study reached a conflicting conclusion, suggesting that the increase had cost jobs.[lxxiv] But the conflicting study has come under fire for its serious methodological errors, which cast doubt on its findings.[lxxv] These problems include the fact that the study excluded 40 percent of the workforce from its analysis, and failed to control for Seattle’s booming economy, which was naturally reducing the number of low-paying jobs as employers raised pay independent of the minimum wage to compete for scarce workers.[lxxvi] (For an expanded explanation, see section immediately above).

Business press reports on Seattle’s economy and job market confirm that it is continuing to thrive as the $15 minimum wage phases in. Today, Seattle has an unemployment rate of just 3.8 percent,[lxxvii] lower than both, Washington State[lxxviii] and the U.S unemployment rates.[lxxix] As Forbes reported in 2017, “Higher Seattle Minimum Wage Hasn’t Hurt Restaurant Jobs Growth After a Year.”[lxxx] Earlier reporting in the Puget Sound Business Journal was titled “Apocalypse Not: $15 and the Cuts that Never Came.”[lxxxi]

San Francisco. After SeaTac and Seattle, San Francisco was one of the first U.S. cities to adopt a higher minimum wage in 2003. Four years later, a study published in Cornell University’s Industrial and Labor Relations Review found that the city had raised pay without costing jobs.[lxxxii] Today, the city’s minimum wage is $14 and will rise to $15 next year. While an updated study of the impact of the city’s higher wage floor is expected in the coming months, all indicators suggest that it is going smoothly. The city’s unemployment rate dropped to 3.9 percent in July of this year[lxxxiii] from 5.7 percent in July 2014[lxxxiv]—the year in which the city adopted its $15 minimum wage—and its restaurant sector sales grew from 5.4 percent to 6.6 percent from 2014 to 2015, a faster pace than comparable cities like New York.[lxxxv]

San Jose. In 2012, voters in San Jose approved a $10 minimum wage by high margins, despite predictions of gloom and doom by opponents.[lxxxvi] Four years later, the City Council, acknowledging the need for more robust wages, unanimously voted to adopt a $15 minimum wage.[lxxxvii] In 2016, University of California researchers released a study of the city’s $10 minimum wage policy. The authors found that the $10 minimum wage had raised pay without costing jobs,[lxxxviii] which confirmed earlier observations reported by the media. As The Wall Street Journal reported a year after full implementation of the new minimum wage and two years before the study was released, “[f]ast-food hiring in the [San Jose] region accelerated once the higher wage was in place. By early [2014], the pace of employment gains in the San Jose area beat the improvement in the entire state of California.”[lxxxix]

Despite opponents’ claims to the opposite, businesses of all sizes are comfortable with minimum wage increases

The positive experiences of jurisdictions that are currently phasing in a $15 minimum wage are some of the reasons that, despite what minimum wage opponents often claim, the majority business owners and executives in firms of all sizes are comfortable with higher minimum wages.

According to polling conducted by LuntzGlobal—an opinion research firm headed by leading Republican pollster Frank Luntz—on behalf of the Council of State Chambers, 80 percent of CEOs, business owners and executives at companies of all sizes support raising the minimum wage in their states, while only 8 percent oppose it.[xc] Among small business owners, 59 percent favor raising the minimum wage, according to a poll by Manta.com.[xci]

Illustrative of the business community’s support for higher wage floors is the fact that a growing number of business owners, business associations, and economists are either voluntarily raising their minimum pay, or have publicly endorsed $15 minimum wage proposals:

- Business Associations: In states that are currently transitioning to a $15 minimum wage, business organizations representing more than 32,000 small businesses either endorsed the $15 wage floor proposal, or simply did not opposed it. These include the Greater New York Chamber of Commerce (endorsed), the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce (endorsed), the Northeast Organic Farmers Association—New York Chapter (endorsed), the Long Island and Westchester/Putnam African-American Chambers of Commerce (endorsed), the Restaurant Association of Metropolitan Washington (endorsed), and the Golden Gate Restaurant Association (did not oppose).[xcii]

- Retailers and Other Businesses: Target, which employs 323,000 workers nationwide,[xciii] recently became the first low-wage chain to announce it will raise its minimum pay to $15 by 2020, citing a need to attract and retain talent, and disproving the myth that a higher wage is an unsurmountable challenge for employers. [xciv] The retail giant is not alone, as a growing number other retailers, financial institutions, restaurants and other diverse businesses of all sizes have made similar announcements, or endorsed minimum wage campaigns.[xcv]

- Economists: Citing a link between low minimum wages, stagnating incomes and growing wealth inequality, a growing number of economists have similarly endorsed Senator Bernie Sanders’ $15 minimum wage bill, which would also gradually eliminate the sub-minimum tipped wage. Endorsers include economists from Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.[xcvi]

The Case for a Gradual Elimination of the Tipped Sub-Minimum Wage in Vermont

Eliminating the sub-minimum wage for tipped workers is crucial to making a real difference in the lives of low-wage workers

The elimination of the sub-minimum wage for tipped workers is crucial to improving the lives and economic prospects of low-wage workers. In a future legislative session, lawmakers in Vermont should consider a gradual elimination of the state’s tipped wage, currently set at 50 percent of the standard minimum wage. Without equal treatment for tipped workers, these workers will become increasingly vulnerable to poverty. As inflation erodes the real value of the tipped wage, tipped workers will become progressively more dependent on the generosity of customers to earn their livelihoods and avoid poverty.

A sub-minimum wage for tipped workers has not always existed. Until 1966, there was no federal subminimum wage for tipped workers.[xcvii] But with the 1966 expansion of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) to cover hotel, motel, restaurant, and other leisure and hospitality employees who had previously been excluded by the FLSA, the law was amended to allow employers to pay tipped workers a sub-minimum wage of 50 percent of the full minimum wage.[xcviii] In 1996, tipped worker’s pay decreased further when a Republican-controlled Congress raised the federal minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.15, but froze the tipped minimum wage at $2.13. This policy decoupled the tipped wage from the full minimum wage for the first time in the history of U.S. wage law, setting up over two decades of a frozen minimum wage for tipped workers[xcix] in most of the nation.

If Vermont adopts a gradual elimination of the tipped sub-minimum wage, it would join the seven “One Fair Wage” states—Alaska, California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington—that do not allow employers to pay their tipped staff a lower wage.[c] Tipped workers in these One Fair Wage states receive the full minimum wage directly from their employers, and their tips function as gratuities should: As supplemental income over and above their wages, in recognition of good service. Although not technically a One Fair Wage state, Hawaii also abolished the sub-minimum wage for most tipped workers, preserving a very limited tip credit of just 75 cents for tipped workers who average at least $7.00 an hour in gratuities.[ci]

This past May, U.S. Senator from Vermont, Bernie Sanders, introduced a $15 minimum wage bill, the Raise the Wage Act (S.1242), which was co-sponsored by 32 other Senators, including Senator Patrick Leahy. Its companion bill in the U.S. House of Representatives (H.R.15) was similarly strongly received, with more than 160 co-sponsors, including Congressman Peter Welch. The Raise the Wage Act, S.1242/H.R.15, would not only raise the federal minimum wage to $15, but would also gradually phase out the sub-minimum tipped wage nationwide.[cii]

Although minimum wage opponents in the restaurant industry often claim that most tipped workers earn high incomes and do not need a raise, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data shows that the typical tipped worker in Vermont earns just a few dollars above the state minimum wage. According to the most recent BLS data, between November 2014 and May 2017, the median wage for restaurant servers in Vermont was $14.40 per hour including tips, and the average was $15.41 per hour, also including tips.[ciii] During the period covered by the BLS data, the applicable minimum wage in Vermont was between $8.73 and $10.00 per hour,[civ] meaning that servers in the state earned between $4.40 and $6.68 above Vermont’s wage floor—hardly the type of high incomes that the restaurant industry claims to be typical.

In addition to restaurant serves, other tipped jobs include car wash workers, nail salon workers, and pizza delivery drivers—notorious sweatshop occupations where pay is often even lower than in the restaurant industry.[cv]

Tipped work is inherently uneven and often unpredictable. While most of us expect to be paid the same for every day or hour we work, for tipped workers this is often not the case. For example, restaurant servers can earn substantially more on Friday or Saturday nights, but much less on other days of the week. Bad weather, a sluggish economy, the changing of the seasons, a less generous customer, and a host of other factors can also cause sudden drops in their tipped income and lead to economic insecurity. Not surprisingly, tipped workers face poverty at twice the rate of non-tipped workers, with waiters and bartenders at even higher risk of poverty.[cvi]

Tipped workers across the country are also significantly more likely to rely on public assistance to make ends meet. Close to half (46 percent) of tipped workers and their families rely on public benefits compared with 36 percent of non-tipped workers.[cvii] Ultimately, shifting the responsibility to pay workers’ wages to customers under the tipped sub-minimum wage system allows employers in a few select industries to benefit from a customer-funded subsidy at the expense of workers’ economic security.

The complex sub-minimum wage system for tipped workers is difficult to enforce and results in widespread noncompliance

The sub-minimum tipped wage system is complex, difficult to implement and plagued by noncompliance. For example, both employers and employees find it difficult to track tip earnings, a task that is often complicated by tip sharing arrangements amongst workers. In addition, when tipped workers’ earnings fall short of the full minimum wage, many will forego asking their employers to make up the difference—as employers are legally required to do—for fear that the employer may retaliate by giving more favorable shifts to workers who do not make such demands.[cviii]

Given the implementation challenges inherent in the subminimum wage system, it is not surprising that a 2014 report by the Obama Administration’s National Economic Council and the U.S. Department of Labor found that one of the most prevalent violations amongst employers is failing to properly track employees’ tips and make up the difference between an employee’s base pay and the full minimum wage when tips fail to fill that gap.[cix] A survey found that more than 1 in 10 workers employed in predominantly tipped occupations earned hourly wages below the full federal minimum wage, including tips.[cx]

Vermont’s restaurant industry is strong, and can afford to adapt to a $15 minimum wage without a tip credit

While restaurant industry lobbyists often argue that eliminating the tipped sub-minimum wage would hurt restaurants and its workers, the facts belie those claims. In particular, the restaurant industry in One Fair Wage states is strong and projected to grow faster than in many of the states that have retained a sub-minimum tipped wage system.

According to projections by the National Restaurant Association (NRA), nationwide restaurant sales are expected to reach $799 billion in 2017, a 4.3 percent increase over 2016.[cxi] In Vermont, restaurant sales were expected to reach $1 billion in 2017. Restaurant and food service jobs currently make up 10 percent of employment in the state, and are expected to grow by a healthy 7 percent over the next ten years.[cxii]

Many of the states with the strongest restaurant job growth do not allow a tipped minimum wage for tipped workers, and require employers to pay tipped workers some of the country’s highest base wages. For example, restaurant employment in California—which has no subminimum wage for tipped workers and is phasing in a $15 minimum wage—is projected to grow by 10 percent during the 2018–2028 period.[cxiii] In California, the minimum wage is now $10.50 per hour for small employers (25 or fewer employees) and $11.00 for large employers (26 or more employees), and the minimum wage will reach $15 for all employers by 2023.[cxiv] In Oregon, where the minimum wage is currently between $10 and $11.25 and will increase to between $12.50 and $14.75 by 2022,[cxv] and which has no tipped sub-minimum wage, restaurant employment is projected to grow by 12.9 percent during that same period.[cxvi] And in Washington State, where the minimum wage is $11.50[cxvii] and will increase to $13.50 by 2020,[cxviii] restaurant employment growth during the same period is expected to grow by 11.4 percent.[cxix] According to the NRA’s own projections, restaurant employment in the seven states without a tipped minimum wage will grow in the next decade at an average rate of 10.7 percent.[cxx]

Moreover, a 2015 Cornell Hospitality Report looked at the impact of minimum wage increases on restaurant employment and business growth levels over twenty years across the United States. It found that raising the minimum wage (including the tipped wage) will raise restaurant industry wages but will not lead to “large or reliable effects on full-service and limited-service restaurant employment.”[cxxi]

You can download the full publication, including the appendices, below.

[i]. Urban Institute and National Housing Conference, The Cost of Affordable Housing: Does it Pencil Out? July 2016, http://apps.urban.org/features/cost-of-affordable-housing/.

[ii]. Public Assets Institute, “Part 2: Family Economic Security,” The State of Working Vermont 2017, December 2017, http://publicassets.org/library/publications/reports/state-of-working-vermont-2017/.

[iii]. National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2017: Vermont, http://nlihc.org/oor/vermont. Comparison to pre-tax monthly income assumes 2,080 hours of work per year.

[iv]. Ibid.

[v]. David Cooper, State Tables on $15 Minimum Wage Impact, Economic Policy Institute, April 26, 2017, https://www.epi.org/files/2017/MW-State-Tables.pdf.

[vi]. Ibid.

[vii]. Ibid.

[viii]. Ibid.

[ix]. Ibid.

[x]. Ibid.

[xi]. Ibid.

[xii]. For information on profits, see recent reporting such as Sarah Whitten, “McDonald’s Shares Surge as Strong Restaurant Sales Show Turnaround is Taking Hold,” CNBC, April 25, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/04/25/mcdonalds-reports-first-quarter-earnings-2017.html; and Jason del Rey and Rani Molla, “Amazon Just Turned a Profit for the Eighth Straight Quarter: A fast-Growing and Profitable Amazon Is a Scary Amazon,” Recode, April 27, 2017, https://www.recode.net/2017/4/27/15451726/amazon-q1-2017-earnings-profits-net-income-cash-flow-chart.

[xiii]. Wayne F. Cascio, “The High Cost of Low Wage,” Harvard Business Review, December 2006, https://hbr.org/2006/12/the-high-cost-of-low-wages. See also Erin White, “To Keep Employees, Dominos Decides It’s Not All About Pay,” Wall Street Journal, February 2005, http://www.post-gazette.com/business/businessnews/2005/02/18/To-keep-employees-Domino-s-decides-it-s-not-all-about-pay/stories/200502180276.

[xiv]. National Employment Law Center, Minimum Wage Basics: Employment and Business Effects of Minimum Wage Increases, September 2015, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Minimum-Wage-Basics-Business-Effects.pdf.

[xv]. Lee Fang and Nick Surgey, “Fearing 2018 Democratic Wave, Right-Wing Lobbyists Are Mobilizing Against a $15 Minimum Wage Push,” The Intercept, December 14, 2007, https://theintercept.com/2017/12/14/minimum-wage-rick-berman-democrats/.

[xvi]. Ibid.

[xvii]. Jack Temple, Tamara Draut and Heather McGhee, Beyond the Debt-for-Diploma system: 10 Ways Student Debt is Blocking the Economic Mobility of Young Americans, Demos, 2012, http://www.demos.org/publication/beyond-debt-diploma-system-10-ways-student-debt-blocking-economic-mobility-young-america.

[xviii]. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2017.

[xix]. National Center for Education Statistics, “Enrollment Trends by Age,” The Condition of Education, April 2016 [as archived April 28, 2017], https://web.archive.org/web/20170428063939/https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cea.asp.

[xx]. Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, Michelle Melton and Eric W. Price, Learning While Earning: The New Normal, Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce, 2015, https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/Working-Learners-Report.pdf.

[xxi]. Sara Goldrick-Rab, Jed Richardson and Anthony Hernandez, Hungry and Homeless in College: Results from a National Study of Basic Needs Insecurity in Higher Education, Association of Community College Trustees, March 2017, http://wihopelab.com/publications/hungry-and-homeless-in-college-report.pdf.

[xxii]. David Cooper, op. cit.

[xxiii]. Urban Institute, Net Income Change Calculator (NICC), http://nicc.urban.org/netincomecalculator/calculator.php.

[xxiv]. David Cooper, op. cit.

[xxv]. Issac Shapiro, Robert Greenstein, Danilo Trisi and Bryann DaSilva, It Pays to Work: Work Incentives and the Safety Net, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 3, 2016, http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-3-16tax.pdf.

[xxvi]. Vermont Department of Taxes, Tax Credits: Vermont Earned Income Tax Credit, [accessed September 29, 2017], http://tax.vermont.gov/individuals/income-tax-returns/tax-credits#veic.

[xxvii]. David Cooper, Raising the Minimum Wage to $15 by 2024 Would Lift Wages for 41 Million American Workers, April 26, 2017, http://www.epi.org/publication/15-by-2024-would-lift-wages-for-41-million/.

[xxviii]. Julie Vogtman & Katherine Gallagher Robbins, The Minimum Wage and the EITC: Complementary Strategies Helping Women Lift Their Families Out of Poverty, National Women’s Law Center, December 2014, https://www.nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/minimumwageandeitcdec2014.pdf.

[xxix]. Deb Brighton, Vermont General Assembly, Joint Fiscal Office, EITC Handouts and Parameters, September 6, 2017, http://www.leg.state.vt.us/jfo/Minimum_Wage_Study_Committee/MWSC%20-%20September%202017/EITC%20Handouts%20and%20Parameters%20-%20Brighton.pdf.

[xxx]. Erica Williams, State Earned Income Tax Credits and Minimum Wages Work Best Together, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 8, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-earned-income-tax-credits-and-minimum-wages-work-best-together.

[xxxi]. Ibid.

[xxxiii]. Hart Research, Support for a Federal Minimum Wage of $12.50 or Above, January 2015, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Minimum-Wage-Poll-Memo-Jan-2015.pdf.

[xxxiv]. Victoria Research, Results of National Poll of Workers Paid Less than $15 Per Hour, October 2015, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Low-Wage-Worker-Survey-Memo-October-2015.pdf.

[xxxv]. National Employment Law Project, Fight for $15: Four Years, $62 Billion, December 2016, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Fight-for-15-Four-Years-62-Billion-in-Raises.pdf.

[xxxvi]. Ibid.

[xxxvii]. National Employment Law Project, “State Campaigns,” Raise The Minimum Wage, https://raisetheminimumwage.com/state-campaigns/.

[xxxviii]. National Employment Law Project, “City Campaigns,” Raise The Minimum Wage, https://raisetheminimumwage.com/city-campaigns/.

[xxxix]. Michael Reich et al (eds.), University of California Press, When Mandates Work: Raising Labor Standards at the Local Level (2014), http://irle.berkeley.edu/publications/when-mandates-work/.

[xl]. San Francisco Public Library, “Proposition L, Minimum Wage (November 4, 2003),” San Francisco Ballot Propositions Database, (accessed September 15, 2017), https://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=2000027201&propid=1696.

[xli]. Ballotpedia, City of San Francisco Minimum Wage Increase Referred Measure, Proposition J (November 2014), https://ballotpedia.org/City_of_San_Francisco_Minimum_Wage_Increase_Referred_Measure,_Proposition_J_(November_2014).

[xlii]. Arindrajit Dube, “Minimum Wages and the Distribution of Family Incomes,” IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Discussion Paper Series (No. 10572), February 2017, http://ftp.iza.org/dp10572.pdf. The author writes, “I find robust evidence that higher minimum wages shift down the cumulative distribution of family incomes at the bottom, reducing the share of non-elderly individuals with incomes below 50, 75, 100, and 125 percent of the federal poverty threshold.”

[xliii]. Kerri M. Raissian and Lindsey Rose Bullinger, “Money Matters: Does the Minimum Wage Affect Child Maltreatment Rates?” Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 72 (2017): 60–70, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916303139.

[xliv]. Randall K.Q. Akee, William E. Copeland, Gordon Keeler, Adrian Angold and Elizabeth J. Costello, “Parents’ Incomes and Children’s Outcomes: A Quasi-Experiment,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Jan. 2010): 86-115, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2891175/.

[xlv]. Lisa Dodson, Randy Albelda, Diana Salas Coronado and Marya Mtshali, “How Youth Are Put at Risk by Parents’ Low-Wage Jobs,” Center for Social Policy Publications, Paper No. 68 (Fall 2012), http://scholarworks.umb.edu/csp_pubs/68/.

[xlvi]. Rajiv Bhatia, Health Impacts of Raising California’s Minimum Wage, Human Impact Partners, May 2014, http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/2014/SB935_HealthAnalysis.pdf.

[xlvii]. Editorial Board, “Raise the Minimum Wage,” Bloomberg, April 18, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-04-16/u-s-minimum-wage-lower-than-in-lbj-era-needs-a-raise.html.

[xlviii]. Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester and Michael Reich, “Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 92, No. 4 (November 2010): 945–964. A summary of the study prepared by NELP is available at http://nelp.3cdn.net/98b449fce61fca7d43_j1m6iizwd.pdf.

[xlix]. Ibid.

[l]. Similar new research has also focused in particular on teen workers—a very small segment of the low-wage workforce affected by minimum wage increases, but one that is presumed to be especially vulnerable to displacement because of their lack of job tenure and experience. However, the research has similarly found no evidence that minimum wage increases in the U.S. in recent years have had any adverse effect on teen employment. See Sylvia Allegretto et al, “Do Minimum Wages Reduce Teen Employment?” Industrial Relations, vol. 50, no. 2 (April 2011). NELP Summary available at http://nelp.3cdn.net/eb5df32f3af67ae91b_65m6iv7eb.pdf.

[li]. Ibid.

[lii]. Hristos Doucouliagos and T.D. Stanley, “Publication Selection Bias in Minimum-Wage Research? A Meta-Regression Analysis,” British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol 47. Issue 2 (May 2009). Abstract available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2009.00723.x/abstract.

[liii]. Jared Bernstein, “Raising the Minimum Wage: The Debate Begins…Again,” On the Economy Blog, February 14, 2013, http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/raising-the-minimum-wage-the-debate-begins-again/.

[liv]. Paul Wolfson and Dale Belman, What Does the Minimum Wage Do? Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2014.

[lv]. Sylvia Allegretto, Arindrajit Dube, Michael Reich, and Ben Zipperer, “Credible Research Designs for Minimum Wage Studies: A Response to Neumark, Salas, and Wascher,” ILR Review, 70(3): 559–592 (May 2017).

[lvi]. Sylvia Allegretto, Arindrajit Dube and Michael Reich, “Do Minimum Wages Really Reduce Teen Employment? Accounting for Heterogeneity and Selectivity in State Panel Data,” Industrial Relations 50: 205-240 (2011), http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/166-08.pdf.

[lvii]. Ibid.

[lviii]. Sandra Black, Jason Furman, Laura Giuliano and Wilson Powell, Minimum Wage Increases By US States Fueled Earnings Growth in Low-Wage Jobs, White House Council of Economic Advisors, December 2016, http://voxeu.org/article/minimum-wage-increases-and-earnings-low-wage-jobs.

[lix]. Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, Ben Zipperer, The Effect of Minimum Wages on the Total Number of Jobs: Evidence from the United States Using a Bunching Estimator, Society of Labor Economists, Apr. 2017, http://www.sole-jole.org/17722.pdf. (Updated Dec. 2017 version can be accessed from the American Economic Association, https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2018/preliminary/1530).

[lx]. Michael Reich, Sylvia Allegretto and Anna Godoey, Seattle’s Minimum Wage Experience 2015-16, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, June 2017, http://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2017/Seattles-Minimum-Wage-Experiences-2015-16.pdf.

[lxi]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, The “High Road” Seattle Labor Market and the Effects of the Minimum Wage Increase: Data Limitations and Methodological Problems Bias New Analysis of Seattle’s Minimum Wage Increase, Economic Policy Institute, June 2017, http://www.epi.org/publication/the-high-road-seattle-labor-market-and-the-effects-of-the-minimum-wage-increase-data-limitations-and-methodological-problems-bias-new-analysis-of-seattles-minimum-wage-incr/.

[lxii]. Ekaterina Jardim, Mark C. Long, Robert Plotnick, Emma van Inwegen, Jacob Vigdor and Hilary Wething, “Minimum Wage Increases, Wages, and Low-Wage Employment: Evidence from Seattle,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 23532, June 2017, http://www.nber.org/papers/w23532.

[lxiii]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, op. cit.

[lxiv]. Arindrajit Dube, “Minimum Wage and Job Loss: One Alarming Seattle Study Is Not the Last Word,” New York Times, July 20, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/20/upshot/minimum-wage-and-job-loss-one-alarming-seattle-study-is-not-the-last-word.html.

[lxv]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, op. cit.

[lxvi]. David Cooper, Testimony of David Cooper before the Massachusetts Joint Committee on Labor and Workforce Development in support of S.1004 and H.2365, Economic Policy Institute, September 25, 2017, http://www.epi.org/publication/testimony-of-david-cooper-before-the-massachusetts-joint-committee-on-labor-and-workforce-development-in-support-of-s-1004-and-h-2365/.

[lxvii]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, op. cit.

[lxviii]. Paul Sonn, “Minimum Wage Hike Alarmists Are Wrong,” New York Daily News, July 25, 2017, http://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/minimum-wage-hike-alarmists-wrong-article-1.3354063.

[lxix]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, op. cit.

[lxx]. Ibid.

[lxxi]. Arindrajit Dube, op. cit.

[lxxii]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, op. cit.

[lxxiii]. Michael Reich, Sylvia Allegretto and Anna Godoey, op. cit.

[lxxiv]. Ekaterina Jardim, et al, op. cit.

[lxxv]. Ben Zipperer and John Schmitt, op. cit.

[lxxvi]. Paul Sonn, op. cit.

[lxxvii]. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economy at a Glance: Seattle, Bellevue-Everett, WA, https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.wa_seattle_md.htm. Refers to preliminary unemployment rate for February 2018.

[lxxviii]. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, Unemployment Rates for States, Seasonally Adjusted, https://www.bls.gov/web/laus/laumstrk.htm. Despite title of page, refers to the preliminary unemployment rate for Washington State for February 2018.

[lxxix]. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Unemployment Rate, https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000. Refers to seasonally adjusted U.S. unemployment rate for February 2018.

[lxxx]. Erik Sherman, “Higher Seattle Minimum Wage Hasn’t Hurt Restaurant Jobs Growth After a Year,” Forbes, January 7, 2017, http://www.forbes.com/sites/eriksherman/2017/01/07/seattle-restaurant-jobs-keep-growing-with-higher-minimum-wages-after-a-year/#3df5b8d71e9f. See also Coral Garnick, “Seattle Jobless Rate Hits 8-Year Low in August,” The Seattle Times, September 16, 2015, http://www.seattletimes.com/business/local-business/state-jobless-rate-stays-steady-at-53-percent-in-august/.

[lxxxi]. Jeanine Stewart, “Apocalypse Not: $15 and the Cuts That Never Came,” Puget Sound Business Journal, October 23, 2015, http://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/print-edition/2015/10/23/apocolypse-not-15-and-the-cuts-that-never-came.html. See also Paul Constant, “You Should Read This Story About Seattle’s ‘Minimum Wage Meltdown That Never Happened,’” Civic Skunk Works, October 23, 2015, http://civicskunkworks.com/you-should-read-this-story-about-seattles-minimum-wage-meltdown-that-never-happened/.

[lxxxii]. Arindrajit Dube et al., “The Economic Effects of a Citywide Minimum Wage,” ILRReview, Vol. 60, No. 4 (2007), http://www.berkeleyside.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Economic-Effects-of-a-Citywide-Minimum-Wage.pdf.

[lxxxiii]. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Metropolitan Area Employment and Unemployment—July 2017, August 30, 2017, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/metro_08302017.htm.

[lxxxiv]. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Metropolitan Area Employment and Unemployment—July 2014, August 27, 2014, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/metro_08272014.htm.

[lxxxv]. First Data, SpendTrend Report: NYC, San Francisco Restaurant Scenes Grow, Albeit in Different Ways, February 2016, http://www.firstdata.com/en_us/all-features/spendtrend-restaurant-report.html.

[lxxxvi]. Ballotpedia, San Jose Minimum Wage Increase Initiative, Measure D (November 2012), https://ballotpedia.org/San_Jose_Minimum_Wage_Increase_Initiative,_Measure_D_(November_2012).

[lxxxvii]. Office of the City Manager, City of San Jose, Minimum Wage Ordinance, (accessed September 15, 2017), https://www.sanjoseca.gov/minimumwage.

[lxxxviii]. Michael Reich, Claire Montialoux, Sylvia Allegretto, Ken Jacobs, Annette Bernhardt and Sarah Thomason, The Effects of a $15 Minimum Wage by 2019 in San Jose and Santa Clara County, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, June 2016, http://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2016/The-Effects-of-15-Minimum-Wage-by-2019-in-San-Jose-and-Santa-Clara-County.pdf.

[lxxxix]. Eric Morath, “What Happened to Fast Food Workers When San Jose Raised the Minimum Wage?” Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2014, http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2014/04/09/what-happened-to-fast-food-workers-when-san-jose-raised-the-minimum-wage/.

[xc]. Mitchell Hirsch, “Leaked Poll for Chambers of Commerce Shows Business Execs Overwhelmingly Support Raising the Minimum Wage,” RaiseTheMinimumWage.com Blog, April 12, 2016, https://raisetheminimumwage.com/leaked-poll-for-chambers-of-commerce-shows-business-execs-overwhelmingly-support-raising-the-minimum-wage/.

[xci]. Kitty French, “Small Business Owners in Favor of Raising Minimum Wage,” Manta.com, April 7, 2016, http://www.manta.com/resources/small-business-trends/small-business-owners-in-favor-of-raising-minimum-wage/.

[xcii]. National Employment Law Project, The Case for a $15 Minimum Wage in Vermont, February 2017, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Case-for-15-Minimum-Wage-Vermont.pdf.

[xciii]. Lauren Thomas, “Target to Raise Its Minimum Wage to $11 Per Hour, Promising $15 By 2020,” CNBC, September 25, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/25/target-to-raise-its-hourly-minimum-wage.html.

[xciv]. Paul Sonn, “Target’s Move to $15 An Hour ‘Blows Up’ This Myth About Raising Minimum Wage,” CNBC, September 27, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/27/targets-15-an-hour-move-busts-minimum-wage-myths-commentary.html.

[xcv]. Business for a Fair Minimum Wage, Business Support for a $15 Minimum Wage, [accessed September 29, 2017], https://www.businessforafairminimumwage.org/news/001151/business-support-15-minimum-wage. See also, National Employment Law Project, The Case for a $15 Minimum Wage in Vermont, February 2017, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Case-for-15-Minimum-Wage-Vermont.pdf.

[xcvi]. Economic Policy Institute, Economists in Support of a Federal Minimum Wage of $15 By 2024, April 25, 2017, http://www.epi.org/files/2017/EPI-minimum-wage-letter-5-30-17.pdf.

[xcvii]. William G. Whitaker, The Tip Credit Provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act, Congressional Research Service, Report for Congress, Order Code RL33348, March 24, 2006, http://www.mit.edu/afs.new/sipb/contrib/wikileaks-crs/wikileaks-crs-reports/RL33348.pdf.

[xcviii]. Ibid.

[xcix]. Ibid.

[c]. Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC) and the National Employment Law Project (NELP), The Case for Eliminating the Tipped Minimum Wage in Washington, D.C., May 2016, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Report-Case-Eliminating-Tipped-Minimum-Wage-Washington-DC.pdf.

[ci]. Hawaii currently allows employers to take a 75 cent tip credit when employees earn $16.25 or more an hour in base wage plus tips. In 2018, the minimum wages plus tips threshold will rise to $17.10. See State of Hawaii Department of Labor and Industrial Relations, Notice to Employees: Tip Credit under the Hawaii Wage and Hour Law, June 2014, http://labor.hawaii.gov/wsd/files/2014/06/Tip-Credit-Notice-with-exhibits-June-2014.pdf.

[cii]. Raise the Wage Act, S.1242, 115th Congress (2017-2018), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1242/cosponsors. See also Raise the Wage Act, H.R.15, 115th Congress (2017-2018), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/15/cosponsors

[ciii]. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, May 2017 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, Vermont, revised March 30, 2018, https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_vt.htm.

[civ]. Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of Labor, Changes in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-Farm Employment Under State Law: Selected Years 1968 to 2017, revised December 2017, https://www.dol.gov/whd/state/stateMinWageHis.htm.

[cv]. ROC and NELP, The Case for Eliminating the Tipped Minimum Wage in Washington, D.C., op. cit.

[cvi]. Sylvia A. Allegretto and David Cooper, Twenty-three Years and Still Waiting for Change: Why It’s Time to Give Tipped Workers the Regular Minimum Wage, Economic Policy Institute, July 2014, http://www.epi.org/files/2014/EPI-CWEDBP379.pdf. According to this analysis, “the poverty rate of non-tipped workers is 6.5 percent, while it is 12.8 percent for tipped workers in general and 14.9 percent for waiters and bartenders.”

[cvii]. Ibid.

[cviii]. ROC and NELP, The Case for Eliminating the Tipped Minimum Wage in Washington, D.C., op. cit.

[cix]. National Economic Council, the Council of Economic Advisers, the Domestic Policy Council, and the Department of Labor, The Impact of Raising the Minimum Wage on Women and the Importance of Ensuring a Robust Tipped Minimum Wage, March 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/20140325minimumwageandwomenreportfinal.pdf.

[cx]. Ibid.

[cxi]. National Restaurant Association, 2017 National Restaurant Association Restaurant Industry Outlook, (last viewed April 17, 2018) http://www.restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/News-Research/2017_Restaurant_outlook_summary-FINAL.pdf.

[cxii]. National Restaurant Association, Vermont Restaurant Industry at a Glance, (last viewed April 17, 2018), http://www.restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/State-Statistics/Vermont.pdf.

[cxiii]. National Restaurant Association, California Restaurant Industry at a Glance, (last viewed April 17, 2018), http://www.restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/State-Statistics/California.pdf.

[cxiv]. Department of Industrial Relations, State of California, Minimum Wage, December 2016, https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/faq_minimumwage.htm.

[cxv]. Bureau of Labor and Industries, State of Oregon, Oregon Minimum Wage, (last viewed April 17, 2018), http://www.oregon.gov/boli/WHD/OMW/Pages/Minimum-Wage-Rate-Summary.aspx.

[cxvi]. National Restaurant Association, Oregon Restaurant Industry at a Glance, http://www.restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/State-Statistics/Oregon.pdf (last viewed April 17, 2018).

[cxvii]. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, Minimum Wage, (last viewed April 17, 2018), http://www.lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Minimum/default.asp.

[cxviii]. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, Initiative 1433: An Overview of the New Minimum Wage and Paid Sick Leave Requirements, (last viewed April 17, 2018), http://www.lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Minimum/1443.asp.

[cxix]. National Restaurant Association, Washington Restaurant Industry at a Glance, (last viewed April 17, 2018), http://www.restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/State-Statistics/Washington.pdf.

[cxx]. ROC and NELP, The Case for Eliminating the Tipped Minimum Wage in Washington, D.C., op. cit. Refers to the period, 2016-2026.

[cxxi]. Michael Lynn and Christopher Boone, Have Minimum Wage Increases Hurt the Restaurant Industry? The Evidence Says No!, Cornell Hospitality Report, Vol. 15, No. 22 (2015), http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=chrreports.

© 2017 National Employment Law Project. This report is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs” license fee (see http://creativecommons.org/licenses). For further inquiries, please contact NELP (nelp@nelp.org).