Explore the Issues

NELP leads the fight for a good-jobs economy. Learn more about our priority issues and how we work to achieve our mission: good jobs for everyone.

Our Priority Issues

Fight Workplace Discrimination in All Its Forms

Your race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, age, conviction record, family or immigration status, or disability should not limit your job opportunities.

Climate Justice at Work

Climate change is shifting what a good job looks like. When danger strikes, workers must be able to take control over their own safety in the workplace.

Strengthen Contracted Workers’ Rights and Employer Accountability

Employers often use contracted labor arrangements to shed responsibility for job quality. NELP works to ensure that employers are accountable to every worker powering their businesses.

Hold Corporations Accountable for Workers’ Rights

Corporations must respect workers’ rights and treat workers fairly and humanely—and be held accountable when they fail to do so.

Upholding Workers’ Rights Is Central to a Good-Jobs Economy

We aim to shift the power balance between workers and employers so that workers can assert their rights and improve their workplace conditions.

Make Workplaces Safer and Healthier

Workers are demanding safe and healthy workplaces and are organizing to make it happen.

Uplift and Protect the Rights of Workers

All workers, regardless of their status, should have the opportunity to thrive in good jobs.

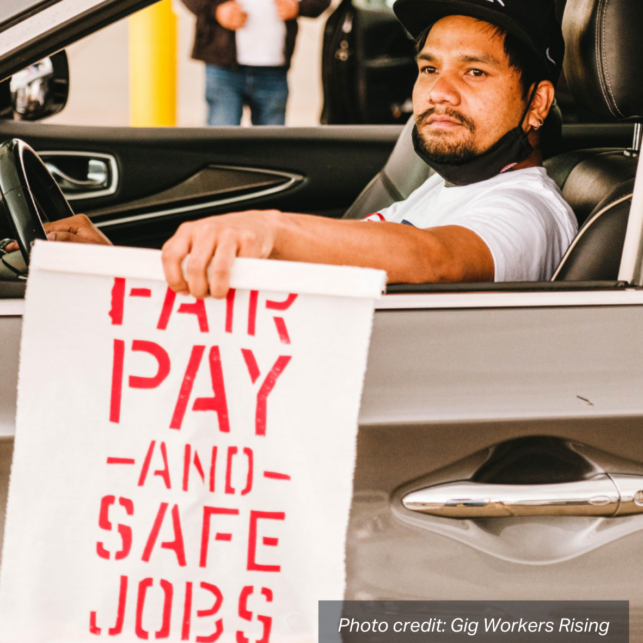

Every Job Should Pay a Living Wage

NELP is fighting to raise the wage floor so it reaches a true living wage that people and families can live on.

Expand Unemployment Insurance for People Out of Work

Workers deserve economic security between jobs. Yet exclusionary and under-resourced unemployment insurance systems leave jobseekers struggling to get by.

Workers Are Building Power Together

In a good-jobs economy, workers build power to collectively shape working conditions and influence the rules and structures of work so that their communities can thrive.

Workers with Records: Reclaiming Rights, Dreams, and Dignity

Workers with records must have access to good jobs that will enable them to sustain themselves, their families and communities, and their dreams.

We're Building a Good-Jobs Economy

Nearly half of all workers in the U.S. make less than $15 per hour. More people than ever are working in jobs that pay too little and offer too few benefits.

We’re leading the fight for a good-jobs economy, in which every single job is a good job, everyone who wants a job can get one, and everyone has economic security between jobs. A good-jobs economy is a just and inclusive economy in which all workers have the opportunity to thrive.

We won’t stop until every job is a good job.

Join the Fight for Good Jobs

There are many ways you can get involved in the good-jobs movement. Take action right now by funding our research, writing to your congressperson, or simply listening and learning about the work we do.

Want to join the fight for a just and inclusive economy where all workers have expansive rights and thrive in good jobs? Find out how to take action now.

Your donation transforms

- tomorrow's laws

- workers' jobs

- people's futures

- families' economic security

Everyone deserves a good job. By giving today, you can support our work as we fight for a good-jobs economy in which every single job is a good job, everyone who wants a job can get one, and everyone has economic security between jobs.