Ride-hailing giant Uber and aspiring “Uber of home services” Handy, along with other tech-companies-cum-service-providers, have joined powerful corporate allies and lobbyists on a far-reaching, multi-million-dollar influence campaign to rewrite worker classification standards for their own benefit—and to workers’ detriment. Their goal: to pass policies that lock so-called “gig” workers who find jobs via online platforms into independent contractor status, stripping them of the basic labor rights and protections afforded to employees and allowing the companies to evade payroll taxes and worker lawsuits. This report sketches the policy campaign, the cast of characters involved, when and where they have mounted efforts, what might be driving them, and the tactics they are using to advance their cause. It concludes with some examples of successful resistance to these efforts, from which lessons can be drawn for the fights to come.

Gig company carve-outs

The emergence of technology-mediated gig work

In the last decade, companies that straddle the technology and service sectors have emerged. These so-called “gig” companies use internet-based technology platforms, accessible via personal computing devices like smartphones, to coordinate and manage on-demand piecework in a variety of service industries, from taxi to food delivery to domestic work.[1] Ride-hailing giant Uber, food delivery service Postmates, and home services provider Handy are well-known examples.

Tech-mediated gig work is the latest iteration of a 50-year-old pattern of workplace fissuring.

Tech-mediated gig work is the latest iteration of a 50-year-old pattern of workplace fissuring—the rise of “nonstandard” or “contingent” work that is subcontracted, franchised, temporary, on-demand, or freelance.[2] Gig companies are simply using new-fangled methods of labor mediation to extract rents from workers, and shift risks and costs onto workers, consumers, and the general public. This recognition helps to debunk a narrative put forward by gig companies that their ”innovation economy” represents an inevitable future of work that must be protected and nurtured exactly as is, at all costs, lest we foil our economic destiny.

According to the latest estimates, gig workers comprise only a small share—about one percent—of the U.S. workforce.[3] In many cities, that share is likely larger—a recent analysis found that if Uber classified its drivers as employees, it would be the single largest private-sector employer in New York City.[4]

Many gig workers, who are disproportionately black and Latino,[5] work in occupations that have long been plagued by industry efforts to erode labor standards—in the form of misclassification and legal carve-outs.[6] In parts of the economy such as the taxi industry and the domestic work sector, the impact of the encroaching gig model reverberates far beyond those engaged by these companies, applying downward pressure on job quality for a much larger set of workers. And gig companies have been joined by more traditional companies to push polices designed to scale up their model across the U.S. economy. Many of the service industries in which gig companies operate have been bastions of organized labor, especially in cities, where gig work is most prevalent.

Gig companies’ misclassification business model

The business model used by many gig companies is based on a deception: to engage the people who actually carry out the core business, and over whose work significant control is exerted, as independent contractors instead of employees. These companies want it both ways: to act like employers but not to be held accountable as such. They impose take-it-or-leave-it non-employee contracts on their workers while setting fee rates, extracting penalties, and dictating when and how workers interact with customers. Due to their practices, they have come under fire for employee misclassification (see sidebar below for more on what employee misclassification entails).

Employee misclassification

Under the current U.S. labor regulatory regime, employee status confers to workers a host of labor rights and protections hard-won by the labor movement beginning in the 19th century. Independent contractor status does not confer those rights and protections; independent contractors are more vulnerable to economic insecurity and workplace mistreatment and physical harm.

Worker classification standards that differentiate employees from independent contractors vary somewhat across U.S. labor laws and regulations, but their core inquiry is usually concerned with whether a worker is truly operating an independent business, free of control by another party.

Since the early days of U.S. labor regulation, businesses have willfully misclassified employees as independent contractors to avoid complying with labor standards and tax laws. Companies have substantial economic incentive to misclassify and can pocket as much as 30 percent of payroll costs when they misclassify workers. Companies that break the law often weigh payroll savings, reaped from eliminating social insurance contributions and obligations to meet labor standards, against the risk of litigation and governmental fines and penalties—risks that have long been quite low due to legal barriers to workers filing claims and proving cases, meager penalty schemes, and under-developed and under-resourced enforcement systems.

Employee misclassification, itself, is a freestanding legal violation in some jurisdictions, and is often an antecedent to payroll fraud and a host of labor standards violations.

Recent years have seen an uptick in employee misclassification claims by workers and innovative efforts by government entities and worker advocates to crack down on the practice. Still, employee misclassification remains pervasive, especially in sectors such as transportation, building services, logistics, home care, and construction. In the last decade, companies that straddle those sectors and the technology sector have emerged. Gig companies like Uber and Handy use (and hide behind) digital technologies to dispatch workers and control their work, while imposing independent contractor agreements on their workers. Many gig companies make filing misclassification claims cost-prohibitive by slipping forced arbitration clauses with class-action waivers into employment contracts.

In addition to its extensive worker impacts, employee misclassification disadvantages responsible businesses that pay their share of payroll taxes and abide by labor standards, shifts liability onto consumers who become sole employers, and depletes social insurance systems.

Handy Technologies is a case in point. Founded in 2012, the New York City–based company has rapidly expanded its reach into residential cleaning, repairs, and other home services. Though the company has enlisted tens of thousands of domestic workers, handymen, and others across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom to provide home services via its platform, it only calls a few hundred people its employees.[7] Like the other gig companies, its business model is built on directly employing as few people as possible, engaging the people who actually carry out its core business—providing home-based services—as independent contractors.

Like many other gig economy players, Handy has faced resistance to its business model. The company exerts significant control over the work of those providing services through its platform, down to the fees they should charge, when and how they can interact with customers, and protocols for using the bathroom. At the same time, the company foists independent contractor agreements on its workers. Due to its practices, Handy workers have filed five class-action lawsuits against the company, alleging misclassification and charges such as underpayment of wages (off-the-clock, minimum wage, and overtime violations), unlawful deductions, and failure to offer rest and meal breaks.[8] In 2017, the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint against Handy alleging that, since at least June 4, 2015, the company “misclassified its cleaners as ‘independent contractors,’ while they were in fact statutory employees.”[9]

Gig company carve-out policies

Rather than change their practices to comply with basic labor standards and take responsibility for the work they control and the conditions they create, Handy, Uber, and several other gig companies have mounted a multijurisdictional policy campaign to rewrite the rules of worker classification to carve themselves out of labor standards and to codify misclassification. At the federal and state levels, they are pushing both legislative and administrative changes that designate all workers who find work via so-called “marketplace platforms” as independent contractors who are not covered by labor and employment protections.

Handy, Uber, and several other gig companies have mounted a multijurisdictional campaign to exempt themselves from labor standards and to codify misclassification.

Uber and Handy’s chief political strategist, Bradley Tusk, summed up the strategy: “What is ultimately a better business decision? To try to change the law in a way that you think works for your platform, or to make sure your platform fits into the existing law?”[10]

The recent gig company carve-out effort can be considered a second phase of carve-outs following a highly successful effort by transportation network companies (TNCs) like Uber and Lyft to exempt TNCs from state and local labor standards.[11] The TNC effort was guided by Mr. Tusk, who has been dubbed “Silicon Valley’s favorite fixer.”[12] Tusk, along with Uber and other TNCs, are back again to push for gig company carve-outs that exempt any “qualified marketplace platform” from a range of labor standards. At a hearing of the first state gig company carve-out bill in 2016 in Arizona, an Uber lobbyist said, “we just passed the same thing in Utah,” referring to a TNC carve-out policy that passed a week earlier. Utah would not pass a gig company carve-out until 2018.[13]

Gig company carve-out policies create a “test” for independent contractor status that simply restates the elements of the current business models of the gig companies.

Gig company carve-out policies create a “test” for independent contractor status that simply restates the elements of the current business models of the gig companies. Indeed, the “test” is rigged so that gig companies will always earn a passing grade and an exemption from labor standards governing the employer-employee relationship. None of the elements of these tests addresses the crucial issue of how gig companies are setting terms of work for those who carry out their core business. Excluded from examination are the main characteristics of a true independent contractor relationship: that a worker is free from the control of the company, provides a service outside the normal scope of the company’s work, and operates a separate business.[14]

In some states, including California, Alabama, and New York, gig companies have sought to sweeten their legislative offer and deflect attention from the labor standards carve-outs by including or informally offering lawmakers (usually Democrats) a small “portable benefits” contribution for gig workers.[15] Thus, for a short-term lobbying expense, and a contribution of around 2 percent of their workers’ incomes, the companies save up to 15 times that amount in the payroll costs they would have borne as employers.[16] These programs offer workers meager benefits, and they undermine existing social insurance systems.

In Texas, an administrative rule change carving gig companies out of state unemployment insurance regulations was proposed by a majority (two of three commissioners) of the Texas Workforce Commission (TWC) in December 2018 and is pending approval.[17] According to documents obtained by the Texas-based Workers Defense Project via a public records request, Handy and Tusk Strategies, both unregistered as lobbyists in Texas at the time, had been in communication with the TWC regarding the carve-out beginning December 2017, supplying model language for the policy.[18]

The federal New Economy Works to Guarantee Independence and Growth (NEW GIG) Act of 2017 (S. 1549/H/R. 4165) is a revision of the Internal Revenue Code that would provide safe harbor to gig companies and other businesses to classify workers as independent contractors if they pass three tests, focusing on the following:

(1) the relationship between the parties (i.e., the provider incurs expenses; does not work exclusively for a single recipient; performs the service for a particular amount of time, to achieve a specific result, or to complete a specific task; or is a sales person compensated primarily on a commission basis);

(2)the place of business or ownership of the equipment (i.e., the provider has a principal place of business, does not work exclusively at the recipient’s place of business, and provides tools or supplies); and,

(3)the services are performed under a written contract that meets certain requirements (i.e., specifies that the provider is not an employee, the recipient will satisfy withholding and reporting requirements, and that the provider is responsible for taxes on the compensation).[19]

The federal bill also includes an income tax withholding provision meant to offset revenue losses that result when employees are reclassified as independent contractors.[20]

Key players

Backed by big finance, Handy, Uber, and Tusk Strategies and a Goliath team of corporations, public affairs strategists, lobbyists, media outlets, policy organizations, and policymakers are pushing for gig company carve-outs at the federal and state levels.

Finance Capital: Before Handy was acquired by ANGI/IAC in late 2018, Revolution Ventures, Tusk Ventures, and 10 other firms invested $110.7 million in the company.[21] Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, Softbank Vision Fund, Morgan Stanley, Toyota, and Tusk Ventures[22] are among Uber’s 97 investors, which have poured more than $24.2 billion into the company.[23] Google parent Alphabet’s CapitalG and General Motors are among Lyft’s 65 backers, investing a total of $4.9 billion.[24] Blackrock, Tiger Global Management, and Founders Fund, are among the 31 entities that have invested $678 million in Postmates.[25] YourMechanic’s top investor is Data Point Capital; 30 investors have contributed $38.2 million to the company.[26] Thumbtack has received $273.2 million from 21 investors, including Baillie Gifford.[27] Airbnb’s $4.4 billion has come from 52 investors, including JPMorganChase, TCV, and CapitalG.[28] Grubhub’s top post-IPO investment of $200 million is from Yum Brands.[29]

Corporations: Gig companies including Handy, Uber, Lyft, GrubHub, Postmates, Thumbtack, YourMechanic, and IKEA-owned TaskRabbit were involved in drafting state-level gig carve-out legislation.[30] Either directly or via third-party lobbyists, Handy, Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, peer-to-peer platform Airbnb, Alticor (owner of gig economy pioneer Amway, the world’s largest direct-selling company[31]), hotel chains Marriott and Hilton, and tech lobby group TechNet (whose membership includes Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Apple, Verizon, and AT&T)[32] have lobbied in support of gig company carve-outs at the federal level.[33] Tech behemoth Amazon has also thrown its considerable weight behind the carve-outs.[34] In October 2018, Handy was purchased by online home services giant ANGI Homeservices (owner of Angie’s List and HomeAdvisor), a subsidiary of media and internet conglomerate IAC.[35]

Public Affairs Strategists: Public affairs firm Tusk Strategies worked with Uber and Handy to devise gig company carve-out policies. Tusk Strategies enlisted Definers Public Affairs to support the gig company carve-out push at the federal level.[36]

Lobbyists: To push for gig company carve-outs at the federal level, Handy and Uber hired Washington, D.C.’s largest lobbying firm specializing in tax issues, Capitol Tax Partners.[37] Uber also hired lobbying firm Invariant LLC, as did TaskRabbit and Marriott.[38] Ballard Partners, a firm led by Trump lobbyist Brian Ballard, successfully lobbied for a gig company carve-out in Florida.[39] Handy and Uber have hired more than 66 lobbyists in 11 states to push gig company carve-outs.[40] The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a right-wing “bill mill,”[41] and the most powerful business lobby group in the United States, is circulating a model gig company carve-out policy.[42] ALEC’s membership includes corporations, policymakers, and lobbyists.Right-Wing Media Outlets: Conservative media outlets including The American Spectator,[43] The Daily Wire,[44] The Daily Caller,[45] The Resurgent,[46] and Salem Radio Network (on the Hugh Hewitt Show[47]), Reason,[48] and Definers Public Affairs’[49] NTK News Network[50] have run pieces supportive of gig company carve-outs.

Right-Wing Think Tanks & Policy Organizations: Leaders from conservative think tanks and policy organizations, including the Cato Institute, the R Street Institute, the Tea Party Patriots Citizens Fund, and the Family Research Council, publicly endorsed marketplace contractor reforms at the federal level in 2017.[51]

Policymakers: Around the country, at least 951 individual policymakers have recorded formal support—in the form of federal or state legislative sponsorship, state legislative yes-votes, gubernatorial signatures, or state rulemaking body yes-votes—for gig company carve-outs.[52]

Multiple fronts

The legislative carve-out effort began at the state level, in Arizona, in 2016

In 2016, Tusk, Uber, and Handy began their legislative march in the state of Arizona, attracted by a favorable political environment and a sizeable market:

We started in Arizona: a state with relatively little union political influence, a tech-friendly governor and legislature, and a market just big enough to matter (Phoenix)…Most campaigns are difficult. This one wasn’t. The inside game worked, our lobbyist got the amendment through.[53]

In 2016, Tusk, Uber, and Handy began their legislative march in the state of Arizona, attracted by a favorable political environment and a sizeable market.

At an Arizona Senate committee hearing in March 2016, Uber’s lobbyist emphatically stated that the bill was penned collaboratively by a coalition of gig companies ready to move it in many more states.

Let me be clear: there’s a coalition of companies—on-demand companies—that have worked on this legislation…companies like Grubhub, Handy, Lyft, Postmates, Thumbtack, YourMechanic, TaskRabbit—all involved with drafting this legislation and putting it forward in over ten states.[54]

However, the political environment in other states was more challenging. In New York, for example, attempts to move legislation were halted by opponents.[55] With gig companies’ largest markets—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago—located in states controlled by Democrats, where Tusk anticipated an “uphill fight at best,” the coalition decided that they needed to pursue a federal strategy. “Our whole thesis was that you can move issues in cities and states where you’d just get stuck forever in the morass of Washington, D.C.,” said Tusk. “But what if the politics make state government an impossible route?”

The legislative carve-out effort continued at the federal level in 2017

In 2017, with Republicans in control of Congress and the White House, the focus shifted to the federal level.

In 2017, with Republicans in control of Congress and the White House, the focus shifted to the federal level. Tusk Strategies Managing Director and Handy point-person Marla Kanemitsu got to work studying federal tax law on worker classification.[56] Below, Tusk recounts the genesis of what would eventually become the federal New Economy Works to Guarantee Independence and Growth (NEW GIG) Act of 2017, and a plan to hide the reform in the 2017 federal tax bill.[57]

Marla Kanemitsu studied the federal tax laws around worker classification. “In theory, we could amend them so that the people who work on sharing-economy platforms are clearly considered independent contractors.”

“This is a law that’s been around since FDR. You want to run a campaign to change it? In Washington, D.C.? In this political climate?”

“Well, aren’t the Republicans talking about tax reform?”

“They always talk about tax reform. That’s what Republicans do.”

“But we’ve got a Republican majority in the House. And the Senate. And a Republican in the White House.”

“I’m not sure he’s really that type of Republican.”

“His whole shtick is being rich. If Congress wants to cut taxes, he’s not going to say no.” She had a point.

“So write an amendment to the tax code, try to stick it into the broader tax bill, and see what happens?”

She nodded. “It’s worth a shot.”[58]

The Senate and House versions of the NEW GIG Act, which is a revision of the Internal Revenue Code that would provide safe harbor to gig companies and other businesses to classify workers as independent contractors, were formally introduced in mid-2017.[59] Their provisions were slipped into the Senate version of the tax bill in December 2017 but were removed at the 11th hour for violating the Byrd Rule, which prohibits the adoption of legislative amendments with a budgetary impact during the reconciliation process.[60]

Federal lobbying records show that, throughout 2018, Handy, Uber, IKEA’s TaskRabbit, Lyft, Airbnb, Alticor, Marriott, and the TechNet coalition continued to lobby Congress on the NEW GIG Act.[61]

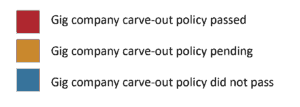

Legislative and administrative carve-out efforts in the states in 2018 and 2019

After the federal defeat, state legislative campaigns were back on the agenda in 2018. Since 2017 saw one public relations disaster after another for Uber,[62] the gig giant became a silent partner, with Handy assuming the role of public face of the campaign. Eleven state bills were introduced in 2018. Bills passed in Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Utah; bills stalled in Colorado, Georgia, and North Carolina; and a California bill was withdrawn by its sponsor.[63] By the middle of 2018, seven states had gig company carve-outs on the books.

At the end of 2018, the Texas Workforce Commission proposed an administrative rule change that would carve gig companies out of the state’s unemployment insurance regulations.[64] Records indicate that a lobbyist had been working the commissioners for several years on gig economy worker classification issues, and had convinced the commissioner representing business to draft the administrative rule.[65] A four-week comment period ended in January, and a decision is forthcoming.[66]

Missouri and West Virginia introduced the first gig company carve-out policies of 2019 in late January.[67] The bills use ALEC’s model language.[68]

Endgame

Enshrining tax breaks and forestalling legal challenges to the gig business model

Carve-out policies seek in part to ensure that gig companies bear no responsibility for employer payroll taxes, which can amount to 30 percent of payroll.[69] On top of those base savings, gig companies may no longer be required to adhere to state wage- and-hour, anti-discrimination and harassment, and health and safety laws; they can further drive down costs by practicing wage theft, pay discrimination, and sacrificing worker safety—all with impunity, since workers will have no grounds for filing claims against those practices.

Gig company carve-out laws in Arizona (2016), [70] Kentucky (2018),[71] and Iowa (2018)[72] are retroactive, so they shut down any pending challenges to the gig business model.

In 2016, Handy CEO Oisin Hanrahan admitted that the gig company carve-outs his company is pushing “would definitely help with some of the litigation that’s in play.”[73] Workers in California, Massachusetts, and Georgia claim in five class-action lawsuits that Handy misclassifies them, underpays wages (e.g., off-the-clock, minimum wage, and overtime violations), unlawfully deducts from pay, and fails to offer rest and meal breaks.[74]

Limiting worker-led organizing and policy efforts to improve gig jobs

Passage of the gig company carve-outs threatens to shut down worker-led innovation in cities and states to address problems created by insecure gig work. Wholesale exemptions in the state laws discourage pro-worker local innovations, such as the Seattle Domestic Worker Bill of Rights, noted below. And the carve-outs would directly undermine attempts to clearly cover on-demand workers as “employees” under a more expansive employee standard offered by the “ABC test” (see final section for more on this test).

Reshaping the future of work and labor regulation

The reach of gig company carve-outs could have broad implications for the future of work and worker protection in the United States. Gig company carve-outs could incentivize a broad range of companies to tweak their business models to use the internet to dispatch workers so that massive swaths of the workforce—entire occupations—could be classified as independent contractors when they are not running a separate independent business.

Occupations that entail on-demand, dispatched work comprise at least one in ten jobs in the United States in 2017.

Occupations that entail on-demand, dispatched work comprised at least one in ten jobs in the United States in 2017. One in five jobs projected to be added to the U.S. market between 2016 and 2026 is in an occupation already commonly dispatched via an online platform.[75]

The world’s largest corporation, e-commerce and cloud-computing giant Amazon,[76] is quietly supporting the carve-outs.[77] Much of its e-commerce delivery operations are powered by on-demand drivers the company classifies as independent contractors. Amazon Flex and Amazon Prime Now workers have filed misclassification lawsuits against the company in recent years.[78] In 2018, Amazon relaunched “Amazon Home Services” using an employee model for its delivery drivers—the company proudly declares, “All our technicians are employees”—but behind the scenes, it is supporting gig company carve-out policies that could turn its employees into independent contractors.[79]

The world’s largest corporation, Amazon, is quietly supporting gig economy carve-outs.

Lobbying records reveal that several companies outside what we think of as the gig economy are supporting the carve-outs. Two of the world’s biggest hotel chains, Hilton and Marriott, have lobbied for a federal bill that includes a gig company carve-out.[80] This backing could signal plans by the hotel industry to make use of gig workers for its hotel cleaning and other operations in the coming years. The hotel industry’s unexpected support for the carve-outs raises the specter of “traditional” employers using carve-out exemptions as a vehicle to deregulate the workplace.[81]

Marriott lobbied for a federal bill that includes a gig company carve-out as its union workforce went on strike in eight cities across the country, eventually winning pay raises, protections against sexual harassment and assault, and bargaining rights over new technology and automation in the workplace.[82] All of those gains could be erased if gig company carve-outs are established and the hotel chain alters the way it dispatches workers to qualify as a “marketplace platform.”

Two of the world’s biggest hotel chains, Hilton and Marriott, have lobbied for a federal bill that includes a gig company carve-out.

Marriott lobbied for a federal bill that includes a gig company carve-out as its union workforce went on strike…

In a conversation with his political strategist, Bradley Tusk, Uber founder Travis Kalanick clearly stated his vision of a driverless future: “I still vividly remember him saying to me, ‘One day, Tusk, no one’s going to own a car. All cars will drive themselves. And you’ll be able to get one just by pressing a button.’”[83] Autonomous transportation and delivery vehicles, digital concierges, and other labor-displacing technologies could be on the horizon in a range of industries that have lobbied for the gig company carve-outs. And, without employee (or independent contractor) rights to form unions, workers do not have bargaining power to shape how job-displacing technology is deployed.

Tactics

Misleading and manipulative messaging

Proponents of the carve-outs have used misleading terms and manipulative messaging about what gig companies do, what the policies they are pushing accomplish, and what it means to oppose them.

Definers Public Affairs, recently revealed to be spreading racist and anti-Semitic stories about critics (including Color of Change and George Soros) of its client Facebook, has used its own in-house conservative media outlet, NTK Network, to talk up a gig economy carve-out at the federal level.

Although often presented as “startups” and “new players,” gig companies are flush with capital from traditional moneyed interests and large venture capital players. Tens of millions in venture capital investment dollars have allowed Handy and Uber to pour resources into message development and media outreach supporting their gig company carve-out campaign. Handy investor Revolution Ventures urged the company to hire Tusk Strategies to mitigate litigation risk and shore up its investment.[84] Tusk later hired Definers Public Affairs as “another front to the war.” Definers Public Affairs is the opposition strategy firm recently revealed to be spreading racist[85] and anti-Semitic[86] stories about critics (including Color of Change and George Soros) of its client Facebook. Definers has used its own conservative media outlet, NTK Network, which a former staffer outed as an “in-house fake news shop,”[87] to talk up a gig company carve-out at the federal level. NTK’s editorial board described the federal carve-out effort as a shield against partisan attempts to destroy the gig economy: “The Obama National Labor Relations Board, trial lawyers, and unions want to see new gig economy companies go out of business by forcing them to classify all their workers as employees and not contractors. This bill ends that.” [88] NTK also published a compilation of right-wing support for the bills.[89]

Misleading messaging on what gig companies do

In lobbying materials for carve-outs, Handy refers to itself as a “modern-day Yellow Pages,”[90] but this characterization is disingenuous and disguises the relationship between the company and its workers. Marketplaces such as the Yellow Pages or the classifieds section of a newspaper are places where true entrepreneurs can post their availability for jobs that they design for customers with whom they may choose to have an ongoing relationship, at a fee that they set. Far from being a neutral “bulletin board,” Handy and other gig companies exert extensive control over their workforces and, in many ways, behave as employers.

Misleading messaging on the aims of gig company carve-outs

Clarity: Carve-out proponents say the gig company carve-outs provide badly needed clarity to businesses that want to accurately determine who is an employee and who is an independent contractor. But their solution for clarity is to devise a test that suits their own business model, hurts workers, and ignores legal standards that other businesses have to meet. Gig companies have actively lobbied against[91] the ubiquitous and decades-old “ABC test” that provides clarity and considers the power dynamic between businesses and workers when attempting to determine whether the worker is truly running a separate business.

Flexibility: Carve-out proponents suggest that only gig companies that classify workers as independent contractors can provide the flexible jobs that workers’ lives demand. During a March 2016 hearing on the first marketplace contractor bill in Arizona, an Uber lobbyist claimed, “The hallmark of the on-demand industry is the flexibility it provides the people who work in it.” She went on to cite an Uber driver survey that found, “90 percent of our drivers pick Uber because they enjoy the flexibility it provides them to have a family, to pursue higher education, to care for a loved one.”[92] But the founder of gig company Managed by Q, which provides on-demand office management services using employees, explained, “There’s a false choice between flexibility and good jobs.” Managed by Q employees control their own schedules and receive training and benefits. Employee delivery drivers at gig company Enjoy can select which days of the week they wish to work.[93] Furthermore, employee status is completely compatible with flexible work arrangements. True flexibility comes with employee benefits like paid time off—for example, paid family leave, sick time, and vacation. These benefits allow workers to balance work and family responsibilities without foregoing pay or putting in overtime. And, employer-funded training and loan support programs facilitate workers’ pursuit of education and training.

Benefits: Proponents of the gig company carve-outs also suggest that the policies are the best way to provide gig workers with access to health, retirement, and other benefits. Retirement security is particularly difficult to achieve through platform-style benefits provision. Avoiding the employer-sponsored model sidesteps many worker protections, including non-discrimination rules, fiduciary protections, leakage (pre-retirement withdrawal) disincentives, and even safeguards against creditors. And it ignores the fact that many of these workers, if properly classified as employees, would already have unemployment insurance, Social Security, and other safety net benefits provided to employees under state and federal laws.

Manipulative messaging on what it means to oppose the carve-outs

Proponents of the carve-outs are pushing the narrative that opponents of the carve-outs are Luddites thwarting economic progress. Bradley Tusk advises gig companies to play on legislators’ fears of being labelled anti-tech and anti-innovation:[94]

[M]ost politicians don’t want to be branded as anti-tech and anti-innovation, so if giving you a win helps them achieve that, you may be in luck.[95]

Did the same politician just crack down on a different startup and doesn’t want to be branded as anti-tech? Can you side with them on another fight to back them off of your issue?[96]

Lobbying and political contributions

Gig companies have invested millions of dollars in rewriting the rules of worker classification in their favor. Since 2015, Handy, alone, has hired at least 66 lobbyists, spending over $970,000 to push for state legislative changes.[97]

Federal lobbying records show that Handy, Uber, IKEA’s TaskRabbit, Lyft, Airbnb, Alticor, Marriott, Hilton, and the TechNet coalition spent almost $4.5 million on lobbyists who advocated for the federal NEW GIG Act in 2017 and 2018.[98]

The TechNet coalition, whose members include gig companies Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Instacart, and DoorDash,[99] spent $280,000 on lobbyists who engaged the U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives, the White House, the U.S. Treasury Department, and the Office of Management and Budget on the NEW GIG Act between the third quarter of 2017 and the fourth quarter of 2018.[100] The coalition may be a channel for gig companies to organize support for state legislative and administrative carve-out campaigns. TechNet’s state policy agenda clearly expresses support for gig company carve-out policies:[101]

The modern workforce requires a flexible employment environment that allows workers to find opportunities that best match their skills, interests, and availability. TechNet opposes efforts to eliminate or severely restrict this essential flexibility, including restrictions on the use of independent contractor and consultant classifications, inflexible overtime rules, and indiscriminate expansion of collective bargaining rules. TechNet supports efforts to develop new avenues and “safe-harbors” that empower companies to voluntarily provide benefits to workers where appropriate without impacting classification outcomes.[102]

The most powerful business lobby in the United States—the American Legislative Exchange Council (better known as ALEC)—has circulated the “uniform worker classification act,” a model policy that facilitates the use of independent contractors by gig and other companies, to its membership.[103] In January 2019, West Virginia introduced a carve-out bill that is a near-replica of the ALEC model.[104]

Several of Handy’s major investors and board members are major political campaign donors, building their sway with elected officials by giving to influential politicians in both major political parties.[105]

Looking ahead

Playing defense

2019 is likely to see multiple attempts to carve gig companies out of labor standards. “We’re working multiple angles to get this done federally…We’re working on legislation and rules in 13 more states too,” revealed Bradley Tusk, in the fall of 2018.[106] An administrative rule that would carve gig workers out of the unemployment insurance program is pending in Texas, and gig company carve-out legislation is pending in West Virginia and Missouri. As gig companies and their allies actively work to erode labor rights and undermine social insurance systems, they will face challenges from worker organizations and their allies, whose successful efforts and tactics to-date are detailed below.

Lessons from successful gig company carve-out pushback efforts

In states such as California, Colorado, Georgia, and North Carolina, three major factors have prevented carve-out bills from becoming law: strong community and labor pushback against the bill, timely national news coverage of the issue, and concerns about fairness and preferential treatment for Handy, Uber, and other gig companies.

Strong community and labor pushback: In states such as California, Colorado, and Georgia, advocacy groups and labor unions have quickly mobilized against the bill, testifying against it in committee hearings, gathering petition signatures, drawing public and media attention to the issue, and lobbying elected officials. The National Domestic Workers Alliance coordinated opposition from national and local groups to the bill and provided legislators with information countering Handy’s claims about the bill. In California, letters from labor groups flooded the bill sponsor, and the bill was eventually withdrawn.[107] In Colorado, at an hours-long hearing of the House Labor Committee, workers and advocates presented testimony about the harm the bill would cause. Though the bill narrowly passed the committee, it was never brought to the floor.[108] In Georgia, several labor unions—the Communication Workers of America, the Southeastern Carpenters Regional Council, and the International Association of Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation (SMART)—provided lengthy testimony detailing the potential negative impacts of the bill.[109] The only group other than Handy that testified in support of the bill was the Georgia Chamber of Commerce.[110]

Raising concerns about anti-competitive effects of policies: During debates within legislatures, elected officials in multiple states have raised concerns about Handy’s active role in setting hourly pay rates and vetting service providers, and about the impact of the proposed bill on local businesses. In Georgia, State Representative Sam Park, who represents Lawrenceville and Gwinnett County, made an impassioned request to his colleagues to oppose the bill, stating, “Government should not be in the business of picking winners and losers.” He added, “The bill…has the potential to put thousands of service-providing small businesses in Georgia at a significant disadvantage to the handful of companies that have asked for this no accountability bill.”[111]

In North Carolina, State Senator Tommy Tucker voiced concerns about the bill’s impact on small businesses like his own. Citing a conversation in which he learned that Handy had taken a 41 percent cut from a $135 handyman job, leaving the worker with $80, he said, “This kind of work…is in direct competition with my HVAC company… I can assure you, you can’t…pay workers’ comp, pay Medicare match, pay Social Security match, and health insurance match, and do all the things that I do with what you’re doing.”[112] The North Carolina bill stalled in the Senate.[113]

Media coverage: In March of 2018, as bills were pending in 10 states, CNN published a news story about the Handy bills wending their way through various state legislatures.[114] The article quoted a brick-and-mortar small business owner and national advocacy groups about the bill’s negative impacts. During the Georgia State Senate committee hearings, legislators referenced the news story and directly questioned Handy’s representative about the criticisms of the bill raised in the article.[115]

Going on offense

Worker organizations and their allies are developing strategies to expand protections for workers engaged by gig companies. Since carve-outs can shut down some of these efforts, connecting defensive strategies and proactive strategies is critical.

Building worker power

Many of the legislative victories related to gig company carve-outs are the result of organizing by unions, worker centers, and community groups. In Seattle, the National Domestic Worker Alliance, Casa Latina, Working Washington, and SEIU 775 led the campaign for the domestic worker ordinance, and the Teamsters and allies won passage of the Drivers’ Collective Bargaining ordinance.[116] In New York, decades-long organizing by the Taxi Workers’ Alliance resulted in standards for transportation network company drivers. In California and Washington, a coalition of unions and worker centers are campaigning for passage of laws clarifying who is an employee under state law. In addition, the Tech Workers Coalition has demanded that Silicon Valley employers afford contract workers the same rights and benefits as their direct hires.[117]

Expanding worker voice in labor regulation

Labor standards boards are tripartite negotiations between employers, workers, and government that many other countries use to set standards for workers in a given sector.[118] Recently, after state- and city-sanctioned wage boards in New York and elsewhere delivered the $15 hourly minimum wage to low-wage workers, there has been renewed interest in these bodies.[119] At least two cities have begun to experiment with them. In Seattle, the City Council approved a domestic worker bill of rights and the creation of a wage and standards commission that includes representation by domestic workers themselves and explores “portable benefits.”[120] In Portland, the City Council passed a resolution giving both Uber and Lyft drivers and affected communities a voice in transportation network company regulation.[121] The resulting Portland standards board will focus on data collection, public safety, driver safety, equitable dispute resolution, and accessibility across the for-hire sector.

Establishing a more expansive definition of employee

In the spring of 2018, the California Supreme Court issued a seminal ruling in the Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court of Los Angeles, No. S222732 (Cal. Sup. Ct. Apr. 30, 2018) class-action misclassification lawsuit, establishing a clearer and more expansive employee classification standard for California—the “ABC test.”[122]

Unlike other worker classification tests, the ABC test places the burden of proof on employers, creating a rebuttable presumption of employment. A worker is an independent contractor if she passes a three-factor test: (A) she is free from control by the putative employer; (B) she is doing work that is outside the usual course of business of the putative employer; and (C) she is engaged in an independently established business.[123]

Workers engaged by gig companies like Handy would not typically pass the ABC test. That’s why Handy and dozens of fellow gig companies have formed a coalition that is seeking administrative and legislative pathways to undermine the Dynamex ruling. Following the decision in April 2018, the coalition sent a letter to the California governor and state legislature urging them to “suspend the application/impact of the Dynamex decision,” citing fears of “an onslaught of litigation” and harm to “the business model of a broad swath of industries and billions of venture capital dollars that are increasingly invested in businesses.”[124] It pressed for a last-minute end-of-session legislative override of the decision. Groups including Uber, Lyft, Caviar, DoorDash, Handy, Instacart, and Postmates created an “I’m Independent” campaign, funded by the Chamber of Commerce, to lobby for a gig company carve-out.[125] In a potential violation of state law, DoorDash e-mailed its employees to ask them to lobby against the bill.[126]

In Washington State, a similar bill with a broad ABC test for who is an employee was introduced, along with a bill establishing a wage and standards board for true independent contractors in transportation, delivery, domestic, and other work.[127] A similar ABC bill is also pending in Oregon.[128]

Ensuring minimum wage protections for gig workers

In New York, the City Council passed a suite of bills that set a $15-equivalent minimum rate of pay for app-based taxi and on-demand drivers. The bills set a floor to stop Uber and other transportation network companies from cutting driver pay and leaving workers with sub-minimum wage take-home pay, as they have done in many markets. The laws also created a cap on vehicles on the road, after a report came out showing that app-based drivers in New York spend 25 minutes of every hour idle, waiting for a fare.[129] Uber has sued the city to overturn the cap, and Lyft and Juno have sued to block the pay minimum wage standard.[130]

Including contract workers in labor standards

In cases where gig workers are true independent contractors, running their own independent businesses, states and cities can include them in existing labor standards or create new ones.

While the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down Seattle’s collective bargaining ordinance in part, it paved the way for states to create and pass their own collective bargaining laws for independent contractors, as they have done for other workers left out of the National Labor Relations Act.[131]

In New York City, a new law ensures that independent contractors are covered by anti-discrimination protections in the New York City Human Rights Law.[132] In 2017, the New York City Council passed a groundbreaking “freelancing isn’t free” law that protects contract workers from wage theft.[133]

[1] Sarah A. Donovan, David H. Bradley, and Jon O. Shimabukuro, “What does the gig economy mean for workers?” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report R44365, Feb 5, 2016, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44365.pdf.

[2] David Weil, The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It, May 2017, http://www.fissuredworkplace.net/ and http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674975446.

[3] The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) added four questions to the May 2017 Contingent Worker Supplement, to measure “electronically mediated work,” which BLS defined as “short jobs or tasks that workers find through websites or mobile apps that both connect them with customers and arrange payment for the tasks,” which is the same basic definition of gig or on-demand work that this brief uses. The BLS estimates that 1.6 million workers, or about 1.0 percent of the workforce, does electronically mediated work, In September 2018, the BLS released its estimate that that 990,000 workers (0.6 percent of the workforce) do electronically mediated work where they provide services in person (working for companies like Uber, Handy, TaskRabbit, etc.). The BLS only asks about gig work in the week prior, so its survey likely underestimates the number of people engaging in this work. The BLS data showed that Black workers and Latino workers are overrepresented in in-person electronically mediated work, and that this type of work is more unstable than work overall (8.7 percent of in person electronically mediated workers report that they do not expect their job to last beyond a year, compared to 3.8 percent of workers overall). More than 72 percent of electronically mediated workers are doing the work as a main job. See Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, “Electronically mediated work: new questions in the Contingent Worker Supplement,” Monthly Labor Review, Sep 2018, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/electronically-mediated-work-new-questions-in-thecontingent-worker-supplement.htm. The JPMorgan Chase Institute also conducted a study of payments directed through online platforms to Chase bank accounts, and found that 1.6 percent of its sample had received gig payments in the first quarter of 2018, while 4.5 percent had received gig payments in the last year. See Diana Farrell, Fiona Greig, and Amar Hamoudi, “The Online Platform Economy in 2018: Drivers, Workers, Sellers, and Lessors,” JPMorganChase, Sep 2018, https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/document/institute-ope-2018.pdf.

[4] James A. Parrott and Michael Reich, “An Earnings Standard for New York

City’s App-based Drivers: Economic Analysis and Policy Assessment,” Report for the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission, Jul 2018, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53ee4f0be4b015b9c3690d84/t/5b3a3aaa0e2e72ca74079142/1530542764109/Parrott-Reich+NYC+App+Drivers+TLC+Jul+2018jul1.pdf.

[5] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, “Electronically mediated work: new questions in the Contingent Worker Supplement,” Monthly Labor Review, September 2018, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/electronically-mediated-work-new-questions-in-thecontingent-worker-supplement.htm.

[6] Sarah Leberstein and Catherine Ruckelshaus, “Independent Contractor vs. Employee: Why independent contractor misclassification matters and what we can do to stop it,” National Employment Law Project, May 2016, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Brief-Independent-Contractor-vs-Employee.pdf.

[7] Handy Overview, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/handybook.

[8] Zenelaj v. Handybook, Inc., 82 F. Supp. 3d 968 (N.D. Cal. 2015)(settled); Washington, et al. v. Handy Technologies, Inc., Case No. CGC-15-546980 (S.F. County Superior Court) filed July 21, 2015; Easton v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (Superior Court of California in and for the County of San Diego) Docket: 2016-00004419; Emmanuel v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (United States District Court District of Massachusetts) Docket: 1:15cv12914; District of Columbia v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (Superior Court of the District of Columbia) Docket: 2016 CA 006729 B (settled); Edwards v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (State Court of DeKalb County, Georgia) Docket: 1:16cv2619 (terminated April 2017); NLRB v. Handy Technologies, Inc., 01-CA-158125.

[9] NLRB v. Handy Technologies, Inc., 01-CA-158125, http://apps.nlrb.gov/link/document.aspx/09031d45825f69ea, see Attachment 1.

[10] Lydia DePillis, “For gig economy workers in these states, rights are at risk,” CNN Money, Mar 14, 2018, https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/14/news/economy/handy-gig-economy-workers/index.html.

[11] Joy Borkholder, Mariah Montgomery, Miya Saika Chen, and Rebecca Smith, “Uber State Interference: How Transportation Network Companies Buy, Bully, and Bamboozle Their Way to Deregulation,” National Employment Law Project and Partnership for Working Families, Jan 18, 2018, https://www.nelp.org/publication/uber-state-interference/.

[12] Connie Loizos, “Silicon Valley’s favorite fixer: Bradley Tusk,” Techcrunch, Jul 1, 2016, https://techcrunch.com/2016/07/01/silicon-valleys-favorite-fixer-bradley-tusk/.

[13] Arizona State Senate, “Senate Commerce and Workforce Development Part 2,” video, Mar 14, 2016, http://azleg.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=13&clip_id=17290, at 2:45:50. Utah HB 201, “Transportation Network Company Amendments,” passed March 10, 2016, https://le.utah.gov/~2016/bills/static/SB0201.html. Utah “marketplace contractor” carve-out not passed until 2018: Utah HB 364 (2018), “Employment Law Amendments,” https://le.utah.gov/~2018/bills/static/HB0364.html.

[14] For example, TN HB 1978 said, “A marketplace contractor is an independent contractor if: (1) The marketplace platform and marketplace contractor agree in writing that the contractor is an independent contractor with respect to the marketplace platform; (2) The marketplace platform does not unilaterally prescribe specific hours during which themarketplace contractor must be available to accept service requests from third-party individuals or entities. If a marketplace contractor posts the contractor’s voluntary availability to provide services, the posting does not constitute a prescription of hours for purposes of this subdivision (a)(2); (3) The marketplace platform does not prohibit the marketplace contractor from using any online-enabled application, software, website, or system offered by other marketplace platforms; (4) The marketplace platform does not restrict the marketplace contractor from engaging in any other occupation or business; (5) The marketplace platform does not require marketplace contractors to use specific supplies or equipment; and (6) The marketplace platform does not provide on-site supervision during the performance of services by a marketplace contractor.” In Georgia, HB 789 contained the same first four elements, but added that the contractor must bear her own expenses, must not be restricted geographically, and does not work from a physical address operated by the platform. TN HB 1978 available at http://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/110/Bill/HB1978.pdf; GA HB 789 available at http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/20172018/177242.pdf.

[15] Sarah Kessler, “The Uber of home-cleaning proposed a law that would retroactively solve its legal issues,” Quartz, Jan 13, 2017, https://qz.com/882656/the-uber-of-home-cleaning-proposed-a-law-that-would-retroactively-solve-its-legal-issues/; CA AB-2765, “Employment benefits: digital marketplace: contractor benefits,” https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB2765; AL SB 363, “Portable benefit plans established for contractors of market place platforms,” https://legiscan.com/AL/text/SB363/id/1753340.

[16] Sarah Kessler, “Handy is Quietly Lobbying State Lawmakers to Declare its Workers Aren’t Employees,” Quartz at Work, Mar 30, 2018, https://work.qz.com/1240997/handy-is-tryingto-change-labor-law-in-eight-states/. See, Alabama SB 363, CA AB 2765, Rebecca Smith and Nell Abernathy, “Little Financial Security if ‘Gig Economy’ Benefits Plan,” Albany Times-Union, Feb 27, 2017.

[17] Justin Miller, “Are Silicon Valley Giants Responsible for a Mysterious New Texas Labor Rule?” Texas Observer, Jan 31, 2019, https://www.texasobserver.org/are-silicon-valley-giants-responsible-for-a-mysterious-new-texas-labor-rule/.

[18] Communication between Texas Workforce Commissioner Ruth R. Hughs and her staff, and third parties engaged in the development, consideration, and/or drafting of the Texas Workforce Commission’s proposed amendments to Subchapter C, Tax Provisions, of §815.134 of the Texas Administrative Code dated December 4, 2018. Obtained by Workers Defense Project via public records request.

[19] NEW GIG Act of 2017, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1549.

[20] Senate Congressional Record, November 29, 2017, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2017/11/29/CREC-2017-11-29-pt1-PgS7408.pdf.

[21] ANGI Homeservices Overview, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/handybook#section-acquisition-details; Handy Funding Rounds, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/handybook#section-investors

[22] Julie Bort, “Regulation-buster and Uber investor Bradley Tusk: Dara Khosrowshahi’s kinder, gentler approach makes Uber seem weak to its foes,” Business Insider, Aug 11, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/bradley-tusk-ubers-gentler-approach-makes-it-seem-weak-to-its-foes-2018-8.

[23] “Uber: Funding Rounds,” Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/uber#section-funding-rounds

[24] “Lyft: Funding Rounds,” Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/lyft#section-funding-rounds.

[25] Postmates Funding Rounds, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/postmates#section-funding-rounds.

[26] YourMechanic Funding Rounds, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/yourmechanic#section-funding-rounds.

[27] Thumbtack Funding Rounds, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/thumbtack#section-funding-rounds.

[28] Airbnb Funding Rounds, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/Airbnb#section-funding-rounds.

[29] Grubhub Funding Rounds, Crunchbase, accessed Feb 21, 2018, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/grubhub#section-funding-rounds.

[30] Arizona State Senate, “Senate Commerce and Workforce Development Part 2,” video, Mar 14, 2016, http://azleg.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=13&clip_id=17290 At 2:46:00.

[31] Petey Menz, “Did Amway Create the Gig Economy?” The Awl, Jul 5, 2017, https://www.theawl.com/2017/07/did-amway-create-the-gig-economy/.

[32] TechNet website, “Members,” accessed Feb 21, 2018, http://technet.org/membership/members

[33] NELP analysis of United States Lobbying Disclosure Act Quarterly Lobbying Reports (Form LD-2). Following publication of this report, NELP was contacted by a Marriott representative, who stated the following: “The hotel industry has been fighting for years to ensure tax and regulatory accountability for short-term rental platforms like Airbnb. Our interest in the NEW GIG Act is to compel the rental platforms to issue 1099-K forms at a dollar threshold that ends the currently rampant under-reporting of income generated by their commercial rental operators. The relevant reporting provisions are in section 2(d) of the bill (p. 14 of the official pdf version). Note, the information contained in 1099 forms can also serve as a critical tool for state revenue agencies (which receive a copy) to track and enforce sales and lodging tax obligations – which, when uncollected, create an unfair pricing advantage for illegal rentals over hotels. We take no position on the independent contractor sections in the bill. Our business model does not lend itself to widespread use of independent contractors and we have no plans to fundamentally alter it or our longstanding relationship with our 110,000+ employees in the U.S.”

[34] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018. p146.

“Obviously, Handy wasn’t’ the only startup who cared about worker-classification reform. Uber jumped in on our side. Amazon did too. Most of the other major sharing-economy platforms were willing to devote dollars to help us push the idea over the finish line.“

[35] Andrew Dodson, “ANGI Homeservices acquires on-demand services startup to attract millennial renters,” Denver Business Journal, Oct 12, 2018, https://www.bizjournals.com/denver/news/2018/10/12/angi-homeservices-acquires-handy.html.

[36] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[37] NELP analysis of United States Lobbying Disclosure Act Quarterly Lobbying Reports (Forms LD-2).

[38] NELP analysis of United States Lobbying Disclosure Act Quarterly Lobbying Reports (Forms LD-2).

[39] Lawrence Mower, “Florida lawmakers approve last-minute change on behalf of powerful lobbyist,” Tampa Bay Times, Mar 12, 2018, https://www.tampabay.com/florida-politics/buzz/2018/03/12/florida-lawmakers-approve-last-minute-change-on-behalf-of-powerful-lobbyist/.

[40] NELP analysis of state lobbying expenditures using public filings compiled by the National Institute on Money in Politics.

[41] Nancy Scola, “Exposing ALEC: How Conservative-Backed State Laws Are All Connected,” The Atlantic, Apr 14, 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/04/exposing-alec-how-conservative-backed-state-laws-are-all-connected/255869/.

[42] American Legislative Exchange Council, “Uniform Worker Classification Act,” Cached webpage Aug 25, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20180825021800/https:/www.alec.org/model-policy/uniform-worker-classification-act/.

[43] Brian McNicoll, “Minimum Wage Gimmicks Are Costing Governments Big Time,” The American Spectator, May 24, 2018, https://spectator.org/minimum-wage-gimmicks-are-costing-governments-big-time-2/.

[44] Jacob Airey, “Senator Thune’s New GIG Act May Be Added To GOP Tax Reform,” The Daily Wire, Nov 7, 2017, https://www.dailywire.com/news/23260/senator-thunes-new-gig-act-may-be-added-gop-tax-jacob-airey.

[45] Ken Blackwell, “A Tax Reform Tweak with Big-Time Benefits,” The Daily Caller, Nov 8, 2017, https://dailycaller.com/2017/11/08/a-tax-reform-tweak-with-big-time-benefits/.

[46] Autumn Price, “Conservatives encourage adding Thune Bill to tax reform legislation,” The Resurgent, Nov 7, 2017, https://theresurgent.com/2017/11/07/conservatives-encourage-adding-thune-bill-to-tax-reform-legislation/.

[47] Hugh Hewitt. “Conservatives encourage adding Thune Bill to tax reform legislation http://theresurgent.com/conservatives-encourage-adding-thune-bill-to-tax-reform-legislation/ … via @AutumnDawnPrice,” Twitter, Nov 8, 2017, https://twitter.com/hughhewitt/status/928351756685316096.

[48] Eric Boehm, “Why the Senate Tax Reform Bill Is a Big Deal for Gig Economy Workers,” Hit & Run Blog, Reason, Nov 10, 2017, https://reason.com/blog/2017/11/10/republican-tax-plan-sharing-economy.

[49] Michael Cappetta, Ben Collins and Jo Ling Kent, “Facebook hired firm with ‘in-house fake news shop’ to combat PR crisis” NBC News, Nov 15, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-hired-firm-house-fake-news-shop-combat-pr-crisis-n936591.

[50] “Key Conservatives Back GOP Effort to Boost Gig Economy in Tax Reform,” NTK Network, Nov 9, 2017, https://ntknetwork.com/key-conservatives-back-gop-effort-to-boost-gig-economy-in-tax-reform/.

[51] “Key Conservatives Back GOP Effort to Boost Gig Economy in Tax Reform,” NTK Network, Nov 9, 2017, https://ntknetwork.com/key-conservatives-back-gop-effort-to-boost-gig-economy-in-tax-reform/.

[52] NELP analysis of state legislative voting records.

[53] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[54] Arizona State Senate, “Senate Commerce and Workforce Development Part 2,” video, Mar 14, 2016, http://azleg.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=13&clip_id=17290.

[55] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[56] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[57] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[58] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[59] The NEW GIG Act of 2017 (S. 1549/H/R. 4165) amends the Internal Revenue Code to create safe harbor for employers to classify workers as independent contractors if they pass three tests, focusing on (1) the relationship between the parties (i.e., the provider incurs expenses; does not work exclusively for a single recipient; performs the service for a particular amount of time, to achieve a specific result, or to complete a specific task; or is a sales person compensated primarily on a commission basis); (2)the place of business or ownership of the equipment (i.e., the provider has a principal place of business, does not work exclusively at the recipient’s place of business, and provides tools or supplies); and, (3)the services are performed under a written contract that meets certain requirements (i.e., specifies that the provider is not an employee, the recipient will satisfy withholding and reporting requirements, and that the provider is responsible for taxes on the compensation). See NEW GIG Act of 2017, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1549

[60] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[61] S.1549 https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1549; H.R. 4165 https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4165.

[62] Sam Levin, “Uber’s scandals, blunders and PR disasters: the full list,” Guardian,Jun 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jun/18/uber-travis-kalanick-scandal-pr-disaster-timeline.

[63] Arizona HB 2652 (2016), “An Act Amending Title 23, Arizona Revised Statutes, by Adding Chapter 10; Relating to Employment Relationships,” https://apps.azleg.gov/BillStatus/BillOverview – 2016 Legislative Session, Bill no. 2652;

Alabama SB 363 (2018), “Portable benefit plans established for contractors of market place platforms,” https://legiscan.com/AL/bill/SB363/2018;

California AB 2765 (2018), “Employment benefits: digital marketplace: contractor benefits,” https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB2765;

Colorado SB 18-171 (2018), “Marketplace Contractor Workers’ Compensation Unemployment,” https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb18-171;

Florida CS/HB 7087 (2018), “An act relating to taxation, https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2018/7087/BillText/er/PDF;

Georgia HB 789 (2018), “Labor and industrial relations; marketplace contractors to be treated as independent contractors under state and local laws; provisions,” http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/en-US/display/20172018/HB/789;

Indiana HB 1286 (2018), “An Act to amend the Indiana Code concerning labor and safety,” http://iga.in.gov/legislative/2018/bills/house/1286#;

Iowa Senate File 2257 (2018), “A bill for an act defining marketplace contractors and designating marketplace contractors as independent contractors under specified circumstances,” https://www.legis.iowa.gov/legislation/billTracking/billHistory?billName=SF%202257&ga=87; Kentucky HB 220 (2018), “An Act relating to marketplace contractors,” http://apps.sos.ky.gov/Executive/Journal/execjournalimages/2018-Reg-HB-0220-2381.pdf;

North Carolina SB 735 (2018), https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2017/Bills/Senate/PDF/S735v5.pdf;

Tennessee SB 1967 (2018), https://legiscan.com/TN/bill/SB1967/2017; and,

Utah HB 364 (2018), “Employment Law Amendments,” https://le.utah.gov/~2018/bills/static/HB0364.html.

[64] Texas Workforce Commission, Proposed amendment to Subchapter C. Tax Provisions, §815.134 https://twc.texas.gov/files/agency/pr-ch-815-status-test-approved-12-4-18-twc.pdf

[65] Texas Workforce Commission, Meeting minutes, Dec 4, 2018, https://twc.texas.gov/files/twc/commission-meeting-minutes-120418-9am-twc.pdf; Texas Workforce Commission, Meeting minutes, Jul 31, 2018, https://twc.texas.gov/files/twc/commission-meeting-minutes-073118-9am-twc.pdf

[66] Justin Miller, “Are Silicon Valley Giants Responsible for a Mysterious New Texas Labor Rule?” Texas Observer, Jan 31, 2019, https://www.texasobserver.org/are-silicon-valley-giants-responsible-for-a-mysterious-new-texas-labor-rule/.

[67] Missouri SB 313 “AN ACT to repeal section 285.500, RSMo, and to enact in lieu thereof two new sections relating to the misclassification of workers,” https://legiscan.com/MO/text/SB313/id/1879711; West Virginia HB 2786, “Uniform Worker Classification Act.” http://www.wvlegislature.gov/Bill_Status/bills_text.cfm?billdoc=hb2786%20intr.htm&yr=2019&sesstype=RS&i=2786.

[68] American Legislative Exchange Council, “Uniform Worker Classification Act,” Cached webpage Aug 25, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20180825021800/https:/www.alec.org/model-policy/uniform-worker-classification-act/; http://www.wvlegislature.gov/Bill_Text_HTML/2019_SESSIONS/RS/bills/hb2786%20intr.pdf;

[69] Catherine Ruckelshaus and Ceilidh Gao, “Independent Contractor Misclassification Imposes Huge Costs on Workers and Federal and State Treasuries,” National Employment Law Project, December 2017, https://www.nelp.org/publication/independent-contractor-misclassification-imposes-huge-costs-on-workers-and-federal-and-state-treasuries-update-2017/.

[70] Arizona HB 2652 (2016), “An Act Amending Title 23, Arizona Revised Statutes, by Adding Chapter 10; Relating to Employment Relationships,” https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/52leg/2r/laws/0210.PDF.

[71] Kentucky HB 220 (2018), “An Act relating to marketplace contractors,” http://apps.sos.ky.gov/Executive/Journal/execjournalimages/2018-Reg-HB-0220-2381.pdf.

[72] Iowa Senate File 2257 (2018), “A bill for an act defining marketplace contractors and designating marketplace contractors as independent contractors under specified circumstances,” https://www.legis.iowa.gov/legislation/BillBook?ba=SF%202257&ga=87.

[73] Josh Eidelson, “U.S. Labor Board Complaint Says On-Demand Cleaners Are Employees,” Bloomberg, Aug 30, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-31/u-s-labor-board-complaint-says-on-demand-cleaners-are-employees.

[74] Zenelaj v. Handybook, Inc., 82 F. Supp. 3d 968 (N.D. Cal. 2015)(settled); Washington, et al. v. Handy Technologies, Inc., Case No. CGC-15-546980 (S.F. County Superior Court) filed July 21, 2015; Easton v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (Superior Court of California in and for the County of San Diego) Docket: 2016-00004419; Emmanuel v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (United States District Court District of Massachusetts) Docket: 1:15cv12914; District of Columbia v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (Superior Court of the District of Columbia) Docket: 2016 CA 006729 B (settled); Edwards v. Handy Technologies, Inc. – (State Court of DeKalb County, Georgia) Docket: 1:16cv2619 (terminated April 2017); NLRB v. Handy Technologies, Inc., 01-CA-158125.

[75] NELP analysis of Occupational Employment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor.

[76] David Streitfeld, “Amazon Hits $1,000,000,000,000 in Value, Following Apple,” New York Times, Sep 4, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/04/technology/amazon-stock-price-1-trillion-value.html.

[77] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018. See p146.

[78] Dan Levine, “Amazon Prime Now drivers sue for unpaid overtime,” Reuters, Oct 27, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-drivers-lawsuit-idUSKCN0SL34120151027; Erica E. Phillips, “Delivery Drivers Sue Amazon, Alleging Violation of Labor Laws,” Wall Street Journal, Oct 6, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/delivery-drivers-sue-amazon-alleging-violation-of-labor-laws-1475714956.

[79] Spencer Soper and Josh Eidelson, “Amazon Takes Fresh Stab at $16 Billion Housekeeping Industry,” Bloomberg, Mar 28, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-28/amazon-takes-fresh-stab-at-16-billion-housekeeping-industry; Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[80] NELP analysis of United States Lobbying Disclosure Act Quarterly Lobbying Reports (Form LD-2).

[81] See note from Marriott at endnote 34.

[82] Samantha Winslow, “Marriott Hotel Strikers Set a New Industry Standard,” Labor Notes, Dec 20, 2018, https://www.labornotes.org/2018/12/marriott-hotel-strikers-set-new-industry-standard.

[83] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018. See p104.

[84] Connie Loizos, “Silicon Valley’s favorite fixer: Bradley Tusk,” Techcrunch, Jul 1, 2016, https://techcrunch.com/2016/07/01/silicon-valleys-favorite-fixer-bradley-tusk/.

[85] Michael Harriot, “Korryn Gaines, Color of Change and How We Know Facebook Doesn’t Care About Black People,” The Root, Nov 30, 2018, https://www.theroot.com/korryn-gaines-color-of-change-and-how-we-know-facebook-1830757887.

[86] Jack Nicas and Matthew Rosenberg, “A Look Inside the Tactics of Definers, Facebook’s Attack Dog,” New York Times, Nov 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/15/technology/facebook-definers-opposition-research.html.

[87] Michael Cappetta, Ben Collins and Jo Ling Kent, “Facebook hired firm with ‘in-house fake news shop’ to combat PR crisis” NBC News, Nov 15, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-hired-firm-house-fake-news-shop-combat-pr-crisis-n936591.

[88] “Key Conservatives Back GOP Effort to Boost Gig Economy in Tax Reform,” NTK Network, Nov 9, 2017, https://ntknetwork.com/key-conservatives-back-gop-effort-to-boost-gig-economy-in-tax-reform/.

[89] “Key Conservatives Back GOP Effort to Boost Gig Economy in Tax Reform,” NTK Network, Nov 9, 2017, https://ntknetwork.com/key-conservatives-back-gop-effort-to-boost-gig-economy-in-tax-reform/.

[90] Handy presentation materials, for North Carolina Revenue Laws Committee meeting, Apr 11, 2018, https://www.ncleg.gov/DocumentSites/committees/revenuelaws//Meeting%20Documents/2017-2018/04-11-2018/Agenda%20Item%20VII%20-%20Handy.pdf.

[91] Letter regarding Dynamex Operations West. v. Superior Court (April 30, 2018) from businesses and business groups to members of the California State Legislature and Governor, Jun 20, 2018, https://www.electran.org/wp-content/uploads/Dynamex-Coalition-Letter.pdf.

[92] Arizona State Senate, “Senate Commerce and Workforce Development Part 2,” video, Mar 14, 2016, http://azleg.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=13&clip_id=17290.

[93] Alana Semuels, “What Happens When Gig-Econoy Workers Become Employees,” Atlantic, Sep 14, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/09/gig-economy-independent-contractors/570307/.

[94] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[95] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[96] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[97] NELP analysis of state lobbying expenditures and public filings compiled by the National Institute on Money in Politics.

[98] S.1549 https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1549; H.R. 4165 https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4165

[99] “Members,” TechNet website, accessed Feb 21, 2018, http://technet.org/membership/members.

[100] TechNet Quarter 3, 2017 federal lobbying report, https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=F686163F-419F-4054-B3F4-C0290EDA3114&filingTypeID=69;

TechNet Quarter 4, 2017 federal lobbying report, https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=16F15877-18C0-4776-B3D2-C8E07428C52E&filingTypeID=78;

TechNet Quarter 2, 2018 federal lobbying report, https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=8DBE3E54-DDC1-48BE-9FE1-8F0DC2703858&filingTypeID=60;

TechNet Quarter 3, 2018 federal lobbying report, https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=63696237-B2BB-445F-AD43-C177BC2A6A8F&filingTypeID=69;

TechNet Quarter 4, 2018 federal lobbying report, https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=11D390AB-2DEA-4DBB-9EF6-34AEC91B9957&filingTypeID=78.

[101] “Public Policy: New Technologies and the Future of Work,” TechNet website, accessed Feb 21, 2018, http://technet.org/state-policy/new-technologies-and-future-of-work.

[102] “Public Policy: New Technologies and the Future of Work,” TechNet website, accessed Feb 21, 2018, http://technet.org/state-policy/new-technologies-and-future-of-work.

[103] American Legislative Exchange Council, “Uniform Worker Classification Act,” Cached webpage Aug 25, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20180825021800/https:/www.alec.org/model-policy/uniform-worker-classification-act/; https://www.alec.org/meeting-session/26038/

[104] West Virginia HB 2786, “Uniform Worker Classification Act,” http://www.wvlegislature.gov/Bill_Text_HTML/2019_SESSIONS/RS/bills/hb2786%20intr.pdf.

[105] NELP analysis of state and federal campaign contribution filings compiled by the National Institute on Money in Politics. Handy Board Member and venture capitalist Joel Cutler, of General Catalyst, has given at least $52,000 to candidates since 2010, with donations split almost evenly between Democrats and Republicans Donn Davis, another Handy Board Member, has given at least $20,000 to candidates in both parties in the last 3 election cycles. Also, in just one election cycle, Venture capitalist and Handy funder Steve Case gave $76,500 in campaign contributions to powerful elected officials from both parties.

[106] Bradley Tusk, The Fixer: Saving Startups from Death by Politics, New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2018.

[107] Georgia State Senate, Insurance and Labor Committee, video, Mar 19, 2018, https://livestream.com/accounts/25225511/events/7946722/videos/171917846.

[108] Colorado SB 18-171 (2018), “Marketplace Contractor Workers’ Compensation Unemployment,” https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb18-171.

[109] Georgia State Senate, Insurance and Labor Committee, video, Mar 19, 2018, https://livestream.com/accounts/25225511/events/7946722/videos/171917846.

[110] Georgia State Senate, Insurance and Labor Committee, video, Mar 19, 2018, https://livestream.com/accounts/25225511/events/7946722/videos/171917846.

[111] Rep. Sam Park comments on HB 789, Georgia House of Representatives, Feb 14, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLxHbXSe5w4.

[112] Handy presentation to North Carolina Revenue Laws Committee meeting, audio file, Apr 11, 2018, https://www.ncleg.gov/DocumentSites/committees/revenuelaws//Meeting%20Documents/2017-2018/04-11-2018/Meeting%2004-11-18%20RevLawsRm544%20930am.mp3. From 2:22:50.

[113] North Carolina SB 735 (2018), https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2017/Bills/Senate/PDF/S735v5.pdf.

[114] Lydia DePillis, “For gig economy workers in these states, rights are at risk,” CNN Money, Mar 14, 2018, https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/14/news/economy/handy-gig-economy-workers/index.html.